[EDITOR’S NOTE: Our month-long series on The Art of Church Architecture draws to a close with Series Editor Ewan Bowlby’s poignant piece on reconciliation reflected in post-war church architecture. We hope you have enjoyed this series. For more information, see our Series Launch.]

In the summer of 2019, politicians, veterans and clergy gathered to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of the D-Day landings which led to the liberation of Western Europe. The various events organised to mark this occasion held together a wide range of responses, shaped by several different motives and purposes. Celebration and gratitude are an important element of the process as appropriate reactions to the Allied victory over Nazism and the sacrifices made by those who secured this success. Yet these sacrifices also elicit feelings of grief, resurfacing painful memories of the death and destruction wrought by both sides in a brutal, bruising campaign. Alongside this, there is also a balance to be struck between past, present and future. Remembrance and commemoration are integral, but so too is a renewed commitment to the future: the solemn promise of ‘never again’.

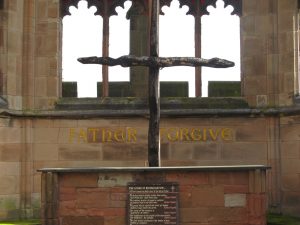

Church architecture has played a vital role in creating symbols of post-World War Two reconciliation which capture this diversity of responses, offering spaces in which each element is reflected and affirmed. A key figure in the reconstruction and reimagining of ecclesial architecture in the aftermath of the war was French architect Augustin Perret, whose work perfectly illustrated how churches could be rebuilt to embody every shade of feeling involved in remembrance and reconciliation. Perret oversaw the reconstruction of Le Havre’s St Joseph Church after it was destroyed by bombing raids in 1944, whilst his work was also a crucial source of inspiration for Basil Spence, the architect responsible for resurrecting Coventry Cathedral as a new international centre for reconciliation. Comparing these buildings and the German response to them provides a way of examining the significance of such projects within the context of the need for a symbolism of peaceful, optimistic remembrance.

Perret saw the ruins of St Joseph in Le Havre as an opportunity to place a ‘spiritual lighthouse’ in the heart of a city that had been almost annihilated by Allied and German bombing raids. As an ardent  ‘advocator and promoter of concrete’ he used this humble, everyday material in a structure which matches its surroundings, complementing the hastily erected functional flats and offices which surround it. Yet as well as mirroring its surroundings, the striking, square-shaped church stands as a ‘symbol of life itself’ that ‘soars up into the sky’, offering a ‘searchlight’ for sailors and a ‘landmark’ for travellers.[1] Its concrete incarnates grief and regret for a city that had to be remade, whilst its towering structure both elevates and transcends Le Havre’s new identity: a lighthouse illuminating the city’s role as a sign of new life and hope.

‘advocator and promoter of concrete’ he used this humble, everyday material in a structure which matches its surroundings, complementing the hastily erected functional flats and offices which surround it. Yet as well as mirroring its surroundings, the striking, square-shaped church stands as a ‘symbol of life itself’ that ‘soars up into the sky’, offering a ‘searchlight’ for sailors and a ‘landmark’ for travellers.[1] Its concrete incarnates grief and regret for a city that had to be remade, whilst its towering structure both elevates and transcends Le Havre’s new identity: a lighthouse illuminating the city’s role as a sign of new life and hope.

Evoking a lighthouse was not the only way in which Perret’s design made use of the symbolism of illumination. Like Abbot Suger’s influential theological justification for the elaborate, extravagant Abbey Church of St Denis, which describes a ‘nobly bright’ building intended to ‘brighten the minds’ of believers,[2] Perret’s plans involved using light and colour within the church as a ‘guide for the prayers going up above’.[3] Perret recruited stained glass artist Marguerite Huré, who he had worked with already in 1922 on the Notre Dame de la Consolation Church in Le Raincy, to help him achieve this effect within St Joseph’s interior. Huré used over fifty shades of colour in glass panels that emphasised the vaunting verticality of the church tower, whilst also exploiting the changing positions of the sun to create a ‘symphonic poem’ of shifting colours over the course of the day.[4]  Just as Suger’s St Denis used ‘many coloured gems’ to fashion a scared site that ‘shines with the radiance of beautiful allegories’,[5] Huré mastered the ‘language of colours’ in a kaleidoscopic display reflecting the varied emotions, memories and hopes attached to the new St Joseph. Deeper, reflective hues gradually transform into ‘shades of yellow and blue’ redolent of the ‘splendour and glory of God’,[6] as the sun catches different aspects of the visual poetry embodied in the glass. Between each dawn and dusk, the light and colours of St Joseph enact moments to match the many moods of remembrance and reconciliation.

Just as Suger’s St Denis used ‘many coloured gems’ to fashion a scared site that ‘shines with the radiance of beautiful allegories’,[5] Huré mastered the ‘language of colours’ in a kaleidoscopic display reflecting the varied emotions, memories and hopes attached to the new St Joseph. Deeper, reflective hues gradually transform into ‘shades of yellow and blue’ redolent of the ‘splendour and glory of God’,[6] as the sun catches different aspects of the visual poetry embodied in the glass. Between each dawn and dusk, the light and colours of St Joseph enact moments to match the many moods of remembrance and reconciliation.

The way in which Perret and Huré exploited the interplay of space, light and time was a key source of inspiration for Basil Spence when he drew up designs for the rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral. The ‘roots’ of his plan lie in the Notre Dame de la Consolation Church which Perret and Huré created together as a memorial to victims of the battle of Ourcq – another example of ‘magnificent stained glass’ used as a medium to support remembrance. Spence incorporated stained glass windows as an ‘extension of the architecture’ in his new cathedral,[7] including nave windows which used ‘rich symbolic colours’ to narrate the journey of a Christian from birth (green), through conflict (red) to eternal life (gold).[8] The influence of Huré’s ‘language of colour’ is immediately apparent in the baptistry window designed by John Piper, which ‘conveyed its message entirely by colour’ and was positioned so that the early-morning sun would catch its central area in a ‘dazzling, elemental trumpet-call’.[9] Like St Joseph, Coventry’s art and architecture unite to frame a daily journey through despair, destruction, hope and forgiveness, using light and colour to highlight different verses in a symphonic poem of reconciliation.

an ‘embrace’ embodying the intermingling of grief, regret and mutual forgiveness that inspires Coventry’s ‘mission of reconciliation’

The affective power of this medium, as well as its capacity to facilitate and reflect the process of reconciliation, can be seen in responses this architecture elicited in German communities. Renate Beck-Ehninger, a German reconciliation leader who witnessed the devastating bombing of Pforzheim in 1944 as a child,[10] describes how Coventry Cathedral gave the church in the German village of Huchenfeld a Cross of Nails, the international symbol of reconciliation. Offered in recognition of a reconciliation project that addressed the lynching of British airmen in Huchenfeld following the Allied bombing of Pforzheim, Beck-Ehninger describes her response to the Cross of Nails using the language of light: ‘can we, for a few minutes, imagine Huchenfeld Church being embraced by Coventry Cathedral, both buildings being transparent like crystals’.[11] Coventry Cathedral’s use of glasswork and colour gave her the imagery to capture what this gesture of reconciliation meant for her community: an ‘embrace’ embodying the intermingling of grief, regret and mutual forgiveness that inspires Coventry’s ‘mission of reconciliation’.

In Ottobeuren Abbey, another German religious community which has come to share in the Coventry ‘Litany of Reconciliation’, a Cross of Nails from Coventry stands in the basilica, positioned so that it is bathed in diverse colours and ‘dazzling, brilliant’ light from the shifting sun. The ‘splendour’ of this vision evokes what Beck-Ehninger describes as an ‘uplifting experience’ – a ‘jubilant and exultant’ celebration of reconciliation.[12] The language of colour and light which Perret and Huré co-created in Notre Dame and Le Havre inspired an ecclesiastical, architectural symbolism which spills out from Coventry Cathedral, illuminating and uniting the shades of reconciliation in churches across Europe. And, as the continent once more finds itself engulfed in tragedy and uncertainty, these churches remain standing as testaments to the true light that continues to shine through the darkness.

[1] ‘St Joseph Church: an aesthetic and spiritual vertigo’ (Le Havre: Le Havre Office de Tourisme, 2005).

[2] Abbot Suger, On the Abbey Church of St Denis, trans. Panofsky, E., cited in Theisen, G., Theological Aesthetics (London: SCM, 2004), p. 114.

[3] ‘St Joseph Church’, Op. cit.

[4] Lecoups, M., cited in ‘St Joseph Church’, Op cit.

[5] Abbot Sugar, Op. cit., p. 114.

[6] ‘St Joseph Church’, Op cit.

[7] Campbell, L., ‘Architecture, War and Peace’, in Lamb, C. (ed.), Reconciling People: Coventry Cathedral’s Story (London: Canterbury Press, 2011), pp. 2-3, 18.

[8] ‘Coventry Cathedral: Artists and Architecture’ (Coventry: Coventry Cathedral and Diocesan Offices, 2008).

[9] Spalding, F., ‘John Piper and Coventry’, Burlington Magazine, vol. 165 (July 2003), p. 500.

[10] Bowlby, C., ‘Hope amid raw memories of war’, BBC News Online (21st December 2002). [ws.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/2595095.stm, accessed 27/11/19].

[11] Beck-Ehninger, R., The Plaque (Pforzheim: Matthias Zeininger, 2002), pp. 134-5.

[12] Ibid., pp. 173-4.