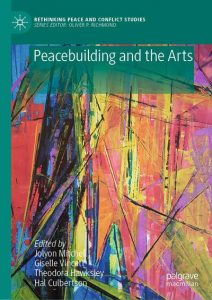

Jolyon Mitchell, Giselle Vincett, Theodora Hawksley, and Hal Culbertson, eds. Peacebuilding and the Arts. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan, 2020, xxii + 483 pp., £89.99 hardcover, £71.50 eBook.

On March 16, 2020, at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and lockdown, I tweeted the following: ‘This present global moment is revealing so much about our human capacity for creativity and charity, as well as our inclination towards ideology and idiocy. ‘Tis truly an apocalypse in the actual sense of the word: an “unveiling” of who we really are’. Now, as 2020 nears its twilight, one might look back upon the year that was and wonder, what did this apocalypse reveal? The recent months have been marked by a persistent global dis-ease, where nature and culture are in a daily contest for generating the most anxiety and devastation. While flooding, wildfires, and hurricanes (not to mention COVID-19) wipe out massive populations of human- and animal-kind, volatile (and often violent) political protests in Hong Kong, Belarus, and the United States are the result of confronting long-gestating structural sins.

What has felt decidedly absent in 2020 is a sense of peace, of Sabbath rest, of shalom. In this, I find myself trying to discern how the arts may contribute in the midst of such overwhelming crises—what might artists do to help, and not harm, during a global pandemic and widespread political turmoil? The publication of Peacebuilding and the Arts,  an expansive collection featuring a variety of perspectives and art forms linked by a common commitment to social justice, feels like a timely or urgent work for this season. The book is a hopeful call to creative action featuring a polyphony of erudite and impassioned voices whose perspectives on both artworks and peace studies are equally enlightening. In their introduction, theologians Jolyon Mitchell and Theodora Hawksley describes the volume’s four recurring themes as constructive communication, bearing witness, empathy, and healing, proposing that their intent is not instrumentalising art, but to generate a dialogue about how creative artistic practices and the practice of peacebuilding can shed light on and build up the Other (pp. 24–25).

an expansive collection featuring a variety of perspectives and art forms linked by a common commitment to social justice, feels like a timely or urgent work for this season. The book is a hopeful call to creative action featuring a polyphony of erudite and impassioned voices whose perspectives on both artworks and peace studies are equally enlightening. In their introduction, theologians Jolyon Mitchell and Theodora Hawksley describes the volume’s four recurring themes as constructive communication, bearing witness, empathy, and healing, proposing that their intent is not instrumentalising art, but to generate a dialogue about how creative artistic practices and the practice of peacebuilding can shed light on and build up the Other (pp. 24–25).

Peacebuilding and the Arts is structured around five artistic mediums: visual arts, music, literature, film, and the performing arts of theatre and dance. Each section features an introductory chapter, two focused ‘case study’ chapters, and a closing chapter of analysis, reflection, and suggestions for future scholarship. Two elements immediately stand out to me as positives: first, there is the inclusion of a wide variety of viewpoints. The editors and contributors, as well as the artists/artworks they address, break from hegemonic (white male) Eurocentric academic approaches which often focuses on so-called ‘high’ art, instead implicitly adopting a global-centric and affirming view of both the arts and peacebuilding practices. In this way, the book incarnates its own peacebuilding ethos—it is a diverse-yet-unified kaleidoscope of rich insights from different scholarly fields and locations which offers a potent model for how such edited collections could/should be done. We are introduced, amongst others, to Korean minjung art; a South African artist using charcoal drawings and animation to address apartheid; contemporary music and storytelling practices in northern Uganda; a powerful documentary film, The Act of Killing, focused on the memory of Indonesian genocide; and the use of live theatre in the context of the present-day Israel/Palestine conflict. I often found myself writing down the names of artists I wanted to look into further, as well as helpful books for consideration (one of the contributors. John Paul Lederarch, is cited repeatedly by the others in their chapters, which has prompted me to seek out Lederarch’s book, The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul of Building Peace).

What has felt decidedly absent in 2020 is a sense of peace, of Sabbath rest, of shalom.

What’s more, and more pragmatically, a second ‘positive’ is the praiseworthy inclusion of colour images. So many publications on the visual arts do not include the artworks themselves, or are limited by the publishers to black-and-white monochromatic images. The more-than-two-dozen colour photographs and images invite the reader into the experiential process of considering the artwork as part of the analysis, rather than as a subsequent Google search. The authors also give in-depth analysis and consideration to the artworks themselves, demonstrating how the unique formal contributions from divergent mediums can afford distinctive benefits within peacebuilding practices. For example, live music can have a different effect than watching a film, which differs from seeing a sculpture or participating in a dance, etc. Broadly speaking, in these analyses, the contributors strike a healthy balance between the sublimity of art (i.e., simply appreciating art for art’s sake) and the functionality of artworks (i.e., how art might inform or transform our imaginations and praxis). Indeed, as Mitchell and Hawksley put it in the introduction, the arts ‘have the ability to express and foster genuine goodness and beauty, justice and humanity’ [p. 10].

Let me offer a personal tangential comment of praise: as someone whose research interests lie mainly in cinema, I appreciated the inclusion of an in-depth ‘film’ section in the book, as cinema is often overlooked or underappreciated in the larger contemporary ‘theology and the arts’ discourse. The four ‘film’ chapters from Joe Kickasola, Robert Johnston, Lizelle Bisschoff, and Olivier Morel are well worth the price of the entire book (even if that price is a bit exorbitant). I was especially impressed by Morel’s proposition of a ‘disarmed cinema’ [pp. 339–354], where documentary film can serve as a reconciliatory medium as well as a means for holding accountable those in political power for their injustices, a notion which feels strikingly relevant in our era of mobile phone footage capturing police violence against citizens. Where much has been argued from Christian moralists on how film can be corruptive or vicious, these chapters present an alternative, how good films—both ethically and aesthetically—might generate virtue and justice in our world.

Art is revelatory; it opens up possibilities for us to remember our past and reimagine our future trajectory.

In sum, Peacebuilding and the Arts is a rich and invaluable resource for scholars, artists, and clergy as it offers a plethora of examples on making peace by making art. To readdress the global ‘apocalypse’ of my opening paragraph, Christ’s proclamation that ‘blessed are the peacemakers’ carries with it rich significance for our present-day conflicts, for both artists and peacebuilders are ‘peacemakers’, eirēnopoios, which is readily affirmed by this hopeful and generative collection. Art is revelatory; it opens up possibilities for us to remember our past and reimagine our future trajectory. If we are wondering, ‘do the arts matter during a global pandemic?’, Peacebuilding and the Arts offers an affirming vision of how and why the arts can bear witness, lament, celebrate, and empathetically promote peace through distinctive and imaginative aesthetic forms.

Image credit

Hands Across the Divide, cc-by-sa/2.0 – © zoocreative – geograph.org.uk/p/478600