[EDITOR’S NOTE: Our series on The Art of Advent: A Painting a Day by Jane Williams begins with Mariah Ziemer’s reflection on the Great Antiphon O Wisdom and the 17th Century painting Holy Wisdom. For more information on this series, see our Series Launch.]

O Wisdom, coming forth from the mouth of the Most High,

reaching from one end to the other,

mightily and sweetly ordering all things:

Come and teach us the way of prudence. [1]

Imagine you are in an art studio walking through a figure drawing class. The model is sitting in a chair at the center of the room, and students fill in the perimeter of the room amidst a forest of easels. Pencils scratch and tap as the students draw, their eyes glancing continuously between the model and their papers. As you make your way about the room, you begin to notice just how different each drawing appears. Even though all the students are observing the same subject matter, each student’s particular angle in relation to the model (among other things) inevitably produces a series of uniquely composed drawings. You, on the other hand, have traversed the room and observed the model from multiple angles.

While beauty may reside in each drawing’s limited perspective (the beauty of isolation, or attentive focus), what might be lacking if each perspective is not viewed in light of the others? Conversely, if, as in the latter instance, you are traversing the room, how might this knowledge and experience impact your own drawing? In light of today’s Advent reflection, I think that we, as fallible human beings, are the students with limited perspectives on the world, whereas God is the one who has ‘traversed the room’. God, in God’s perfect wisdom, sees all, and all that is seen by God is seen fully and perfectly. A.W. Tozer writes, ‘Wisdom, among other things, is the ability to devise perfect ends and to achieve those ends by the most perfect means.… Wisdom sees everything in focus, each in proper relation to all, and is thus able to work toward predestined goals with flawless precision’. [2] This divine wisdom is mysterious. Elusive. Hidden. I suppose if God sat down to create a drawing, it would be an indescribably beautiful drawing—but God would not reveal it to human eyes; God’s drawing would remain a secret. Tozer finds comfort in such mystery:

It is heartening to learn how many of God’s mighty deeds were done in secret, away from the prying eyes of men or angels. When God created the heavens and the earth, darkness was upon the face of the deep. When the Eternal Son became flesh, He was carried for a time in the darkness of the sweet virgin’s womb. When He died for the life of the world, it was in the darkness, seen by no one at the last. When He arose from the dead, it was ‘very early in the morning’. No one saw Him rise. It is as if God were saying, ‘What I am is all that need matter to you, for there lie your hope and your peace. I will do what I will do, and it will all come to light at last, but how I do it is My secret. Trust Me, and be not afraid’. [3]

And yet, perhaps there is a hint. Perhaps something is revealed, something born out of God’s sheer goodness and infinitely gracious love. Indeed, as Williams reiterates, we can catch a glimpse of God’s divine wisdom in the person and redemptive work of Jesus Christ. The sweet face of the infant Christ lying in a manger—however unexpected, according to humanity’s standards—is ‘wisdom embodied’. [4]

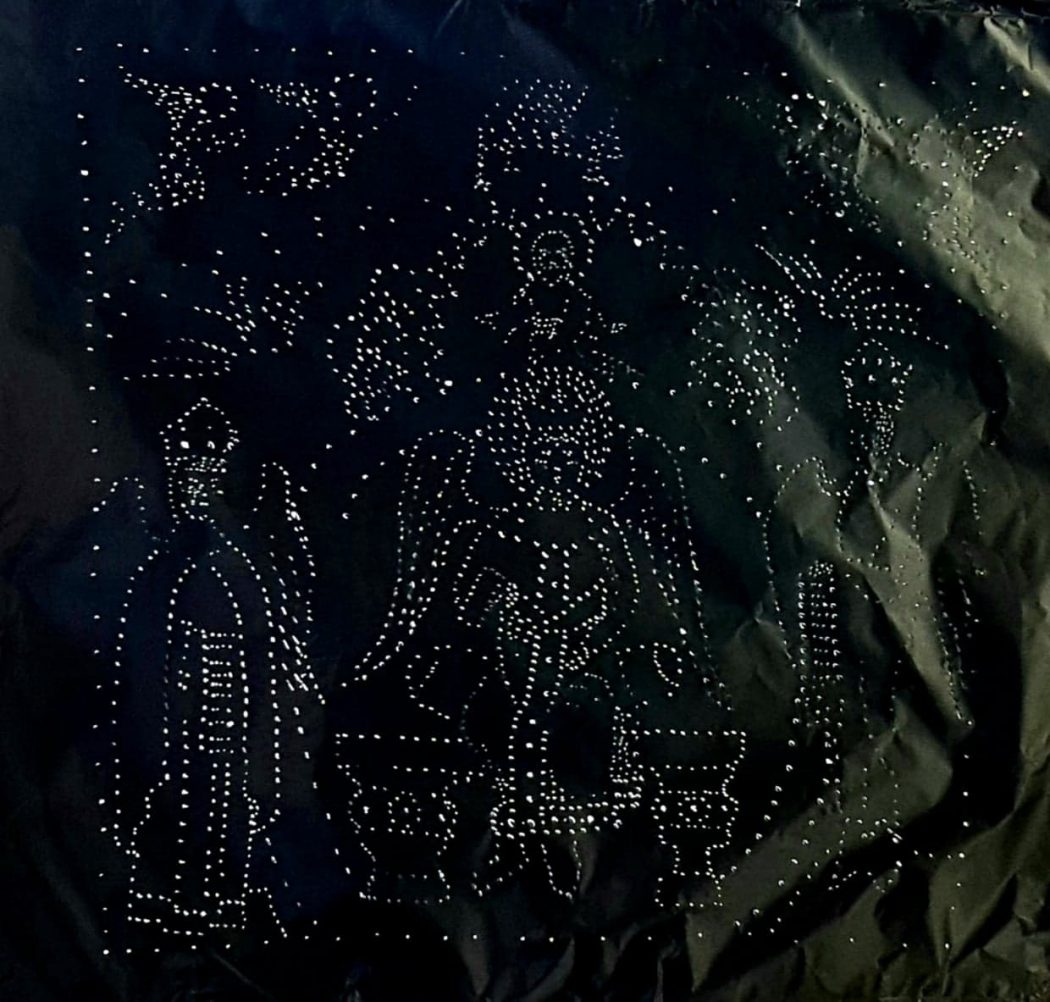

If we look closely at today’s painting (a seventeenth-century Russian icon—one ‘drawing in the room’, if we are to continue the metaphor), [5] we can note how various visual elements support this notion of Christ as the figurehead of Divine Wisdom. Starting with the colours, we see a vibrant display of reds, greens, and golds (a colour scheme that seems fitting for Christmas!). Red in particular creates visual continuity between each ‘layer’ of the earthly and heavenly realms (through the figures’ robes, wings, and God the Father’s throne at the top of the icon), and it highlights Sophia, the personification of Holy Wisdom, in the center of the piece. [6] Her face is illuminated with the intensity of this red, which may be why Williams describes her as ‘forceful and attractive’ and ‘full of energy and passion’. [7] Two squares at the bottom of the painting ground Mary and John the Baptist, but as our eye moves upward, the lines tend to soften in forming rounder shapes. We see the large, green circle behind Sophia, the gold halos of Sophia and Christ, the circle framing the figure of Christ, and the soft arch of the line dividing the starry sky from the gold sky below it. All of the colours, lines, and gestures point upward to Christ and further on to the Father, for the Father and Son are perfectly unified in this divine wisdom.

Holy Wisdom (1670s)

The painting may still leave some struggling to see the embodiment of Wisdom in the world in which we live and labour. The angelic images of John the Baptist and Mary fail to capture our worldly condition – perhaps fueling the emphasis on the hiddenness of Wisdom. But whether we are left awestruck or disappointed in the mystery of this secret of Divine Wisdom which, as Tozer points out, calls us to trust, we are not left with nothing to do. While Williams highlights the Proverbs 8 description of Wisdom’s role with God in creation ‘at the beginning’, [8] Paul suggests that the wisdom of God is not restricted to the craftsmanship of the universe nor to mere intellect but is truly the wisdom of action. Rev. Professor Trevor Hart, in a Sunday reflection on Wisdom, comments:

The wisdom of God, Paul suggests, is not restricted to the unrivalled draughtsmanship and craftsmanship involved in creating a world like ours, with all its beauty and complexity and wonder; though no doubt we see it reflected there too. But the wisdom of God, Paul insists, is much bigger, much deeper than any mere divine brilliance. Because it encompasses, too, the knowledge of how to deal with a world which, as ours has, goes seriously wrong. [9]

While this true Wisdom hidden through the ages (1 Corinthians 2:7) ‘is much more than intellectual prowess to the power of “n”’ and not the sort of thing that clever people in universities can ever attain, [10] Hart concludes:

[The true wisdom of God] is the understanding of how to respond when the world goes seriously awry and is engulfed in evil and suffering. And it involves God getting God’s hands dirty, and taking the worst that evil and suffering are able to inflict on anyone, and wrestling with them and submitting to them, in order, finally, to defeat them. It is, in other words, the cross – the crucified Jesus who is himself none other than the one through whom all things were made – who is the true wisdom of God, revealed at last in flesh and blood form to accomplish the world’s redemption and do what has to be done ‘for our glory’, for our sharing in God’s own glory. For it is that, and not suffering and death, for which we were made. [11]

Perhaps what we are left with from this painting and reflection is the redemptive hope which Advent anticipates and an awareness of the action we can take in response. During this season, the O Antiphons offer a response of prayer, and so I also offer mine, inspired from my own engagement with Holy Wisdom – both the painting and the antiphon:

Lord, help us learn how to trust your hidden wisdom while seeking it in the face of Christ. May our minds, hearts, and souls be ever attuned to your Spirit so that we may walk in the way of wisdom, as Christ so perfectly demonstrates. We praise you for the miracle of the incarnation in your grand, redemptive narrative. Help bring us closer to you through this part of your story. Amen.

[Editor’s note: Karen McClain Kiefer assisted with the completion of this article.]

Image credits

Banner Image: Liv Nino, O Wisdom.

Holy Wisdom, 1670s: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Holy_Wisdom_(1670s,_Yaroslavl_Art_Museum).jpg.

Notes

[1] The Great O Antiphons, sixth century.

[2] A. W. Tozer, The Knowledge of the Holy: The Attributes of God (1961; repr. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 60.

[3] Ibid., 63-64.

[4] Jane Williams, The Art of Advent: A Painting a Day (London: SPCK, 2018), 76.

[5] Sophia the Sacred Wisdom. Yaroslavl Art Museum, 1670s. https://www.icon-art.info/topic.php?lng=en&top_id=439&mode=img.

[6] ‘Sophia’, a feminine noun, is the Greek term for wisdom. Cf. two sixteenth-century paintings of Sophia/Wisdom: Titian’s Wisdom (1560) and Paolo Veronese’s Allegory of Wisdom and Strength (1565).

[7] Williams, 76.

[8] Proverbs 8:22-36; Williams, 74.

[9] Trevor Hart, ‘O Wisdom Advent Reflection for the Second Sunday before Advent’, Saint Andrew’s Episcopal Church, St Andrews UK, 17 November 2019. http://www.stasstas.com/reflection–study.html.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.