If you come in a space with a big flame of fire you will get burnt, and you cannot say: ‘This is the symbol of a flame’, because you will die of the heat of this flame. So is Christ not a symbol for something. It is the substance in itself. It means life. It means power, the power of life… Without this substance of Christ the earth would already have died.[1]

Joseph Beuys believed that Western society, and particularly Germany, had become spiritually bankrupt. During WWII, Beuys flew in the German Luftwaffe and his plane was shot down. As the legend goes, a tribe of tartars found him and managed to keep him alive by wrapping him in animal fat and felt until German soldiers eventually brought him to a hospital. After WWII, Beuys watched his country and Europe fall into dark times. He believed that Western society was wounded.

The wound is a potent and pervasive theme in Beuys’ work. His environment Show Your Wound (1974) spoke of death and the possibility of regeneration, and exhorted Germans to “show your wound.” In his famous I Like America and America Likes Me (photo above, 1974), the wound motif reappears. The performance begins at Beuys’ home in Germany where he is wrapped in felt, placed on a stretcher and driven by ambulance to the airport. When he arrives in New York, he is met by another ambulance that takes him to a gallery. Beuys then prepares a room for himself and a coyote to live together for several days. He had only a shepherd’s staff and a blanket of felt for protection. Over the course of their cohabitation, Beuys is able to tame the wild coyote, and at one point the coyote actually lays harmlessly upon his lap. In this remarkable piece the wound is recognized and healed. As one commentator puts it, this encounter becomes a “reconciliation between the New World and the Old World, fraternization between different races, animal and man, nature and culture.”[2]

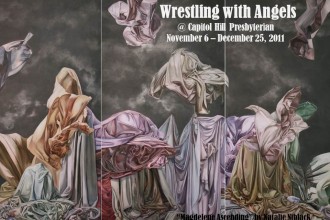

Beuys’ work could be described as prophetic. The prophet is one who, as Walter Bruggemann says, embodies an “alternative consciousness” in such a way that he “serves to criticize in dismantling the dominant consciousness”[3] and “energize persons and communities by its promise of another time and situation toward which the community of faith may move.”[4] It is clear from nearly all of his works and from his numerous statements, that Beuys’ main concern was to nurture, nourish, and evoke an alternative consciousness. Beuys thought that the key to transforming society is found in what he calls Social Sculpture: the shaping of society through the collective creativity of its members. Beuys believed that human freedom begins with the recognition that everyone is an artist.

For Beuys, there is no potential for social change in a materialist world and, thus, no possibility of experiencing the freedom that Christ offers. This is why Beuys urgently appealed to humanity to restore their connection with a spiritual reality. So, what are our wounds, and how might art be brought into service to heal them?

[1] Joseph Beuys, Interview with Louwrien Wijers, Joseph Beuys Talks to Louwrien Wijers, (Holland: Kantoor Voor Cultuur Extracten, 1980), 46.

[2] Lucrezia De Domizio Durini, The Felt Hat: Joseph Beuys A Life Told, trans. by Howard Roger Mac Lean, (Milano: Edizioni Charta, 1997).

[3] Walter Brueggemann, The Prophetic Imagination, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2001) 3.

[4] Ibid.

Jim – Art may indeed be capable of producing healing in some sense, but I think some wounds are permanent (read “thorn in the flesh” ) and the source of our receptivity to grace. Beauty both wounds and heals us. Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger spoke of the “wound of beauty” in his essay of 2002 (http://www.crossroadsinitiative.com/library_article/601/Co…nal_Joseph_Ratzinger.html). I think (Beuys’ prophetic performances notwithstanding) art seldom truly “transforms” society or changes anything. It may provide an “alternative consciousness” and certainly poetry and painting offer fresh vision at times — but the project of social change is, to my mind, another thing altogether. Perhaps Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion heals something in us but I don’t think it changes the world — not does Shakespeare’s The Tempest or Lear or Hamlet — nor Dante’s Divina Comedia. What all these great works of art do is give us pleasure, uplift our hearts and imagination, and at their best make space for hope and charity. Maybe that is social change, but I don’t think great art is had by setting out to change the world.

Thanks for your comment. I am sceptical of Beuys’ ‘Social Scupture’ idea as it is a bit too utopian, political and optimistic for my tastes. But I do think that I agree with him that art can play a role in transforming people and society.

You may be right that great art is not had by setting out to change the world, but I can think of many artists who involve social change (or at least the hope of social change) as an important aspect of their creative process and the work itself. In the wake of Beuys’ influential work it is not hard to think of examples (Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Suzanne Lacey, Mel Chin, and Krzysztof Wodiczko come to mind). But it seems to me that the relationship between art, ethics, and society has often been a close one in the history of western art (positively one might think of Aristotle’s influencial notion of catharsis, or negatively one might consider iconoclasms that speak out against the corrupting effects of artistic images upon society). Even the Bible might be held up as a work of art that transforms society (to paraphrase Eric Auerback, the bible has a way of demanding that the reader fit him or herself into its story).

So, if we could continue the dialogue, I would like to know if you think that one can and should speak of art transforming the world, and if you could elaborate further upon the sense in which you think it is inappropriate to speak of art transforming the world. Also, I too think that some wounds are permanent, but I would also say that those wounds can be ‘healed’ in the sense of being redeemed (participating in the new humanity). Did you take ‘healed’ to be something different from ‘redeemed,’ or are you pointing towards an even more radical idea of permanent wounds?

Thank you also for the link to the essay by Cardinal Ratzinger. I was not aware of it and I look forward to reading it!

Jim – glad for the dialogue.

The phenomenon of utopian art manifestos issued every few years in the early 20th century is an interesting illustration of my point. Much of the art generated was forgettable or only important as an historical moment — not as stand-alone timeless masterpieces. Contrastingly, many of the great works of Western literature, art, and music were crafted with the prevailing ethos of art embedded in an existing social structure — even sometimes as a servant alongside or within corrupt political powers. George Steiner is eloquent in his analysis of this in his T.S.Eliot Lectures collected in the volume In Bluebeard’s Castle. Briefly, in a poignant essay entitled In A Post-culture, he questions the age old assumption that study of the liberal arts and humanities actually shapes human moral character for the better. The Nazi art connoisseurs and literate SS officers nicely put to rest this fond idea.

My point is related — in that I believe art can indeed afford catharsis and bring an uplift to the human imagination — but it is powerless to redeem. Great artists seem to know this, and they use their immense talent to act as scribes of the human condition — both celebrating and descrying its paradoxical nature: the angel-beast. I do hope for redemption, and as a painter I strive to make images that offer hope. But I do not imagine myself changing the world. I am merely bearing witness.

Bruce, I suppose that I do think that art can play a much larger role in changing society than what you have described. And I am not sure why artists should avoid incorporating social change into their creative practice. As it happens, I studied painting as an undergraduate, and so I can recognize that for a painter there are usually many more pressing concerns (when it comes to making a painting) then ‘transforming society.’ But, at the very least, I would still want to say that a painting can play a role in transforming society, or healing our wounds, because it can help us to imaginatively explore important ideas and questions (what does it mean to be human?, what does it mean to live a good life?, etc.) And it would seem that ideas play an important role in transforming society. Beuys, as you may know, took this notion very seriously and tried to communicate his ideas in a variety of ways, especially the idea that all people are creative. But his notion of social sculpture goes beyond the communication of ideas.

So, I have a couple questions about what you have just said. First, you say that art is powerless to redeem. I wonder if you could expand on this. In one sense, human beings are powerless to redeem because only Christ is the source of human redemption (we cannot save ourselves). But in another sense, one could argue that Christ offers humanity a share in his redemptive activity on earth. It seems to me, that this is one dimension of the image of God, and this is one dimension of the purpose of the Church. So does human artistry have some share in God’s redemptive activities, or is there something about human artistry that makes it incapable of redeeming?

Second, your discussion of great artists in both of your posts is curious to me. I suppose it raises questions for me about why these artists are ‘great’ and why we ascribe significance to them. I think that all art is embedded in actions (Wolterstorff) or is a prop in the games we play with it (Walton). Its significance would seem to be determined by its capacity to serve the actions it is embedded in or the games that we play with it well. It seems to me that many ‘great’ artists are doing more than being scribes to the human condition. Much western art is devotional art that attempts to engage the viewer in devotional practice and not simply to show the human condition. Grunewald’s alterpiece is a remarkable picture of tragedy, sorrow, and death but it almost certainly had devotional practices associated with it (prayer, contemplation, liturgical services, etc) and I think that these practices do play a role in transforming society. How is Grunewald making a painting that engages Christians in devotional practice different from Felix Gonzalez-Torres making a work of art that engages the audience in a practice that raises awareness about AIDS? Why say that great artists are simply being scribes of the human condition, or making images that offer hope? Why can’t they do this and more? Why are some artists great and others not?

I hope that these questions are helpful, and I am very curious to know what your answers are. It may be that our apparent disagreement may rest upon different ideas of what ‘transforming society’ means. I intended to mean it in the broadest sense possible (something like communicating ideas, or what you have described as “uplifting our hearts and imagination), but I also think art can play a role in more ‘direct’ social change as one might find in the work of Tim Rollins and the KOS where his creative practice directly affects (and in many ways for the better) a particular community. Perhaps if you said more about what you mean by ‘transforming society’ that would be helpful as well.

Bruce, thanks for the link to Ratzinger’s essay, it seems worthy of it’s own post and reflection here and its relationship to VonBalthasar, Heidegger, and Adorno. Also, I was very pleased to see some of your art, especially the ‘Second Adam Tryptych.’

Certainly one might look more to materialist/economic forces for ‘world changing’ agents among other places, but I am not quite ready to altogether dismiss art (and more broadly aesthetics, as Adorno argues, that ‘ethics is a sub-category of aesthetics’) of any social transformative influence. Jim suggests something similar below where he states, “‘great’ artists are doing more than being scribes to the human condition” (I am waiting for you to respond to Jim before I say anything more about that). What struck me most in your post is your comment about “merely bearing witness.” I have not thought of myself as an artist as ‘bearing witness‘ merely or otherwise, but I now very much value that way of looking at it (rather than a product/producer pandering for other witnesses?) thanks. One last thing while looking for that darn Adorno quote above, I came across this from his MM: “The only philosophy which can be responsibly practiced in face of despair is the attempt to contemplate all things as they would present themselves from the standpoint of redemption. Knowledge has no light but that shed on the world by redemption: all else is reconstruction, mere technique. Per-spectives must be fashioned that displace and estrange the world, reveal it to be, with its rifts and crevices, as indigent and distorted as it will appear one day in the messianic light. To gain such perspectives without velleity or violence, entirely from felt contact with its objects—this alone is the task of thought. . . . Beside the demand thus placed on thought, the question of the reality or unreality of redemption itself hardly matters.” I think it would be worth it to take some time and compare that with the Cardinal Ratzinger essay where he says, in part, “So it is not merely the external beauty of the Redeemer’s appearance that is glorified: rather, the beauty of Truth appears in him, the beauty of God himself who draws us to himself and, at the same time captures us with the wound of Love, the holy passion (“eros”), that enables us to go forth together, with and in the Church his Bride, to meet the Love who calls us.” Obliged.

I appreciate your thoughtful posts Jim.

Dan & Jim – I so appreciate the thoughtful dialogue…I am afraid at the moment that I have little time to give your questions the careful response that they deserve. I will only say here that I am not arguing against change or redemption or art as a kind of social leaven. I am only saying that artists who start out by trying to change the world end up almost always with something tendentious or propagandistic, not with great art. I don’t think the aesthetic impulse is the same as the activist impulse — not that both cannot exist in the same person — but they are distinguishable and should be. By bearing witness I mean to say that the artist does not primarily act upon political or social grounds, but stands in relation to what is and responds — with criticism, perhaps — but mostly with vision. In that way perhaps she changes the world — by glimpsing something alternative in the midst of her attempts to record both what is and what might be. But I do not think that William Blake’s poetry was a manifesto for a different social order so much as a vision for how things might be. He was not a utopian but he was a visionary. More another time, as I must run these next days…cheers.

Bruce, thanks for these comments. This definitely clarifies some of you earlier comments. I can certainly see how art that is made with the intention of affecting social change can easily become propaganda. And your suggestion that an aesthetic impulse is distinguishable (though not completely separate?) from an activist impulse seems a good one, and perhaps a topic that is worth pursuing. It makes me think that I should do some reading on the relationship between aesthetics and ethics, and then write a couple blog posts as there are clearly a lot of interesting questions here.

Dan, Thank you for your comment and interesting quotes. I definitely need to read that Ratzinger essay. I just wanted to take this opportunity to say thanks for you comments on my earlier post about worldviews and works of art, and that I was only recently able to respond to the conversation that unfolded in my absence. It was a very interesting converation and I was sadly without an internet connection at the time.

I am looking fwd to your post on Benedict’s essay. Let me encourage you with one last quote that I as an Icon writer/painter found insightful. “An icon does not simply reproduce what can be perceived by the senses, but rather it presupposes “a fasting of sight.” Inner perception must free itself from the impression of the merely sensible, and in prayer and ascetical (sic) effort acquire a new and deeper capacity to see, to perform the passage from what is merely external to the profundity of reality, in such a way that the artist can see what the senses as such do not see, and what actually appears in what can be perceived: the splendor of the glory of God, the “glory of God shining on the face of Christ ” I think that phrase “a fasting of sight” deserves some reflection, it also seems to suggest a transcending of so many critical modernist tropes, while parts of the rest of the essay seems a but reactionary and moralistically counter-post-modernist. Obliged. ps St.Andrews seems like such an extraordinary place to study and teach, youall are blessed.