[Editor’s Note: As our series ‘Christian Doctrine and the Arts’ enters its final week, Halil Avci considers the role of art in the Christian and Islamic traditions, and its relevance in dialogue between them. For more information on this series, see the series introduction.]

“The task of the poet and the artist is to keep the Infinite before our eyes and to remind us that it ever dwells within our souls”.[1a]

In thinking about the relevance of the arts in interreligious dialogue, I seek first to shed light on the general question ‘what is Art’, and what is its role in the traditions of Christianity and Islam. Secondly, I’ll look at how the arts can create a ‘space’ for dialogue to open oneself to the ‘other’, and will consider how the artefact speaks for itself and infuses the heart to meet in silence and the enjoyment of the presence of the Beautiful.

What is Art?

To ask the question of the relevance of the arts in interreligious dialogue we first have to ask ‘what is Art?’ How I talk of the arts is very much from a religious perspective. To quote Richard Viladesau, ‘Religion is […] a way of “seeing” and “feeling” the world, as well as a way of conceiving it, in relation to God’.[1] This belief in God sets everything out of oneself in relation to Him, providing a mirror to oneself, a pointer to Him, or a resemblance of Him. The nature of God in relation to creation tells us about our place in this world and eventually the right things to be known, done, and made—and given an account of the human person as created in the image of God, this bears directly upon the arts. To explain further, let us consider Karl Rahner, who writes,

Whatever is expressed in art is a product of human transcendentality by which, as spiritual and free beings, we strive for the totality of all reality […] It is only because we are transcendental beings that art and theology can really exist.[2]

That is to say that the arts are not only a source of theological reflection and religious experience but also a ‘tool’ or a way in which the Spirit finds its expression. The artist, then, should not be understood as an empty vessel, but rather as the creative act of the Spirit. In the making of art, the artist is fully in the presence of God and the Spirit overflows through forms of expression in poems, paintings or music. That is, an answer to the question ‘what is Art’ might be to say that every form of art is both an expression of one’s inner disposition and of the Spirit; further, art expresses encounter with the Other and makes accessible to others a glimpse of the Beauty of God. To put it another way, the arts are the works of the Spirit as an expression of human spirituality that implicitly embodies transcendence and as such manifests itself in different forms and contexts. In the following, I’ll investigate the ‘findings’ of the traditions of Christianity and Islam and look at how they made the ‘encounters’ with the Divine accessible to others and how that might be a place to meet others.

The Arts in Christianity

As Caitlin Brosious helpfully summarises, ’In Christianity, the Arts has been an ongoing development of liturgical, communal, and aesthetic expressions of the Christian faith and its tradition’.[3] Furthermore, as ‘the Crucifixion became synonymous and recognizable to the way Christ died, over time the cross logically became the symbol that represented Christ’.[4] In other words, the cross reflects upon the passion, death and resurrection of Christ and serves as a reminder for people to come. Any work of art in Christianity, especially the icon, is not merely a piece of art, but rather, as Rowan Williams states, ‘the icon is part of an act of worship’. [5] That is to say that the arts have been received in Christianity as things to ‘pray’ with. Cardinal Ratzinger goes a step further, saying,

As Caitlin Brosious helpfully summarises, ’In Christianity, the Arts has been an ongoing development of liturgical, communal, and aesthetic expressions of the Christian faith and its tradition’.[3] Furthermore, as ‘the Crucifixion became synonymous and recognizable to the way Christ died, over time the cross logically became the symbol that represented Christ’.[4] In other words, the cross reflects upon the passion, death and resurrection of Christ and serves as a reminder for people to come. Any work of art in Christianity, especially the icon, is not merely a piece of art, but rather, as Rowan Williams states, ‘the icon is part of an act of worship’. [5] That is to say that the arts have been received in Christianity as things to ‘pray’ with. Cardinal Ratzinger goes a step further, saying,

to admire the icons and the great masterpieces of Christian art in general, leads us on an inner way, a way of overcoming ourselves; thus in this purification of vision that is a purification of the heart, it reveals the beautiful to us, or at least a ray of it.[6]

He speaks of the multidimensionality of icons and the arts, explaining that the sight of an icon is a kind of worship in the sense that it resembles the beauty of Beauties, God, and deeply connects the soul of the faithful to Him and purifies his sight. The admiration of beauty is relational in the sense that the perceiver is not merely looking; rather it is the grace upon him to see properly, to see in the gaze of God.

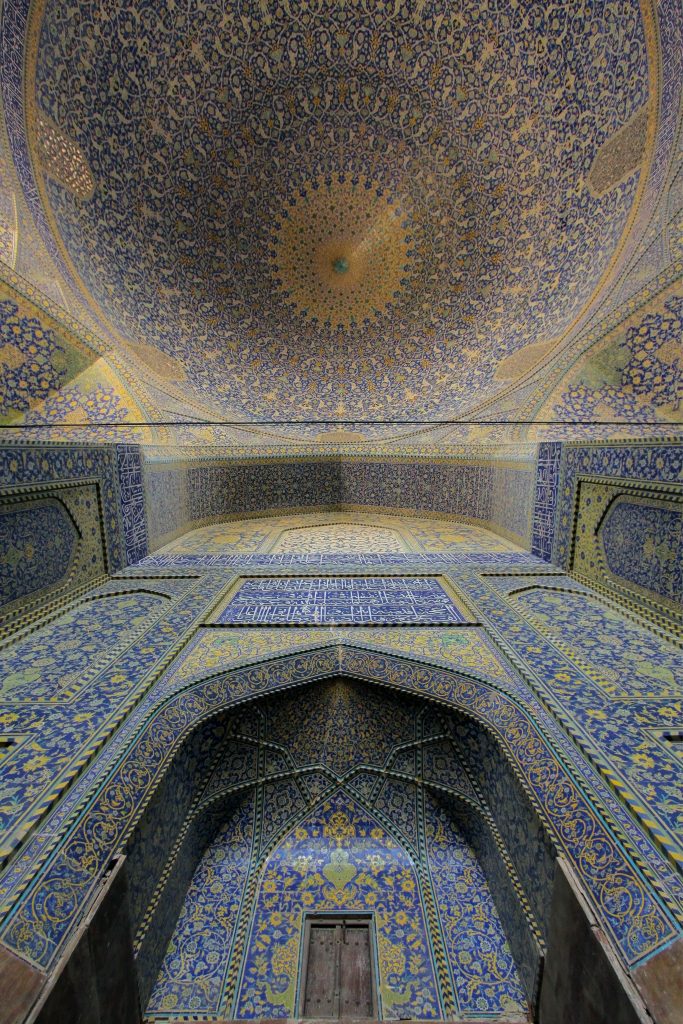

The Arts in Islam

In this section, I seek to understand the arts in Islam and look at how the Beautiful is understood and expressed. To give a first glance at Islamic arts I’ll quote from Murata and Chittick’s Vision of Islam.

The major contours of Islamic art are implicit in the form of the Koran, the Word of God. God expressed himself to the Islamic community through speech. In order to preserve and maintain God’s speech, the Muslims had three fundamental duties: To recite the Koran, to copy the Koran, and to embody the Koran. […] It states in the Koran “God is beautiful, and He loves beauty,” and “God loves those who do what is beautiful.” Muslims with any sensitivity toward beauty have attempted to do things beautifully.[7]

That is to say that essential to Islam’s vision of the arts, it seems, is first and foremost the engagement with the revelation, the Word of God. Thus, the dialogue of the faithful with the Divine forms and informs Islamic art.

For Muslims sensitive to the spirituality that informs their religion—that is, sensitive to the fact that all beauty and all reality belong to God— artistic forms become a way of perceiving the signs even more directly than they are found in the natural world.[8]

art expresses encounter with the Other and makes accessible to others a glimpse of the Beauty of God.

The arts in Islam have been received as a means to see God in all creation or at least to know that God is the beginning and end of all things. Seyyed Hosein Nasr states in the foreword to Titus Burkhardt’s Art of Islam: Language and Meaning that,

Islamic art is at last revealed to be what it really is, namely the earthly crystallization of the spirit of the Islamic revelation as well as a reflection of the heavenly realities on earth, a reflection with the help of which the Muslim makes his journey through the terrestrial environment and beyond to the Divine Presence Itself, to the Reality which is the Origin and End of this art.[9]

Islamic art can therefore ‘lead […] to a more or less profound understanding of the spiritual realities that lie at the root of a whole cosmic and human world’.[10] However, as Murata puts it,

what strikes [one] the first time encountering Islamic arts is the relative lack of naturalism and representationalism in general, and the total lack of sculpture. Partly, this has to do with the prohibitions of figurative art issued by the Prophet.[11]

Because of the lack of figural representation in Islamic arts, the artist found different forms to express what is beautiful. We see this, for instance, ‘in the form of floral and vegetal representation, known as the Arabesque, which are widely used in traditional ornamentation’.[12] Also, ‘calligraphy can be found in abundance within Islamic art, as letters themselves become symbolic instrument’.[13] We see that all illustrations are ways in which the arts shed light on the deep nature and beauty of things and serve as a means of reflection of the Word and eventually of God.

Because of the lack of figural representation in Islamic arts, the artist found different forms to express what is beautiful. We see this, for instance, ‘in the form of floral and vegetal representation, known as the Arabesque, which are widely used in traditional ornamentation’.[12] Also, ‘calligraphy can be found in abundance within Islamic art, as letters themselves become symbolic instrument’.[13] We see that all illustrations are ways in which the arts shed light on the deep nature and beauty of things and serve as a means of reflection of the Word and eventually of God.

Thus, whether the arts be Christian or Islamic, the focus is on the Word of God. Not only do the artefacts resemble the Word, but they also give a glimpse of the eternal Love and Beauty of God. God is Beautiful and He knows all the ways in which to bring about the beautiful, in effect revealing Himself in varied ways. Seeking to understand God’s action in the world through interpretative models in the arts, we’ll investigate in the next part the role of the arts in Interreligious dialogue.

The Role of the Arts in Interreligious Dialogue

Among other thought-provoking statements, on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of the Second Vatican Council’s Nostra Aetate on the Relation of the Catholic Church to Non-Christian Religions, Pope Francis recalled the following: ‘the benevolent and attentive gaze of the Church on religions (is that) she rejects nothing that is beautiful and true in them’.[14] The essentiality of beauty stands at the forefront of such an encounter and of interreligious dialogue in particular. As Brosious says,

The importance of interfaith dialogue seems to be reflecting one of the most crucial doctrines in all Abrahamic religions, namely, the love of God and the love of neighbour. A pluralistic viewpoint is widely considered to be necessary for open and constructive interfaith dialogue.[15]

With this in mind, it is the sincere, curious, and faithful who go out to look for the beauty in others, to see the way in which the ultimate Other reveals himself. The one defines himself through the sight of the other, which is to say that one cannot be defined without the other. In other words, we all need others to become who we are, and the other might hold what we need to come to ourselves. Michael Barnes puts it this way:

Sufficient for the moment [is] to note that at its heart is the experience of learning about the ways of God that are often hidden yet disclosed in any encounter with the other—wherever that other is to be discerned.[16]

The aim of all such encounters is first and foremost to bring people from each tradition together, and thus, to listen to each other and to learn from others’ relationship to God.

On that note, one innovative approach to interfaith dialogue involving the arts highlights the centrality of encountering the other in silence. This may seem contradictory since we want people in interreligious dialogue to talk to each other, However, it is precisely through silence that we may listen with reverence and let art speak to us, gathering side by side with people from many different traditions and beliefs.’ As practitioner of interfaith dialogue Mario I. Aguilar says,

Language becomes a problem because this togetherness in prayer and contemplation, in togetherness and silence, requires the language of the heart, the language of a contemplative and mystical theology that does not find adequate language of expression within the daily language of commerce, work and the markets.[17]

In this regard, the dialogue is centred around religious experience, in which we share the works of the Spirit with others through making and enjoying art. Therefore, ‘the spiritual use of art and imagination [serves] as a precursor to successful interfaith dialogue’.[18]

Thus, clearly the arts are crucial for creating a space in which people of different beliefs can enjoy the works of the Spirit—both art, and each other. And as we behold the beauty of the great masterpieces of art, we are invited to close our eyes and enjoy being in the sight of the other and the ultimate Other’.[19]

Image Credits

Celtic Cross beside the Rideau Canal. Photo by Shankar S. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Celtic_crosses#/medi/File:A_Celtic_cross_beside_the_Rideau_Canal_(20758739101).jpg

Ernst Thevis and Fabian Rabsch (artwork), Imruz (photo). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hafis-Goethe-Denkmal_(cropped).jpg

Notes

[1a] Mary Anderson, “Art and Inter-Religious Dialogue,” in The Wiley-Blackwell companion to inter-religious dialogue, ed. by Catherine Cornille (Hoboken: Wiley, 2013), 99.[1] Richard Viladesau, Theological Aesthetics: God in imagination, Beauty, and Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 17.

[2] Karl Rahner, quoted in Richard Viladesau, Theological Aesthetics, 18.

[3] Caitlin Brosious, Emma Burgin, Andrea Dyer, Maggie Knobbe, Art Making to Inform Dialogue Across Spiritual Otherness in the Therapeutic Space (LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations, 2020), 908, 31.

[4] Brosious, Art Making to Inform Dialogue Across Spiritual Otherness in the Therapeutic Space, 32.

[5] Kallistos Ware, Quoted in Rowan Williams, Ponder These Things: Praying with Icons (Brewster: Paraclete Press, 2006), x.

[6] Joseph Ratzinger, “The Feeling of Things, the Contemplation of Beauty,” Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Vatican website, 2002.

[7] Sachiko Murata, William C. Chittick, The Vision of Islam: The foundations of Muslim Faith and Practice (London: I.B. Tauris Publishers, 1996), 242.

[8] Sachiko Murata, The Vision of Islam, 244.

[9] Seyyed Hosein Nasr, Quoted in: Titus Burckhardt, Art of Islam: Language and Meaning (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2009), viii.

[10] Jean Louis Michon, Quoted in: Titus Burckhardt, Art of Islam: Language and Meaning (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2009), xi.

[11] Sachiko Murata, The Vision of Islam, 243.

[12] Brosious, Art making to Inform Dialogue Across Spiritual Otherness in the Therapeutic Space, 21.

[13] Ibid., 21.

[14] Pope Francis, “In His Own Words,” In Pope Francis and Interreligious Dialogue: Religious Thinkers Engage with Recent Papal Initiatives, edited by Harold Kasimow, Alan Race (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 55.

[15] Brosious, Art making to Inform Dialogue Across Spiritual Otherness in the Therapeutic Space, 22.

[16] Michael Barnes SJ, “Interreligious Dialogue,” In The Oxford Handbook of Mystical Theology, edited by Edward Howells and Mark A. McIntosh (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 627-628.

[17] Mario Aguilar, The Way of the Hermit: Interfaith Encounters in Silence and Prayer (London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2017), 25.

[18] Brosious, Art making to Inform Dialogue Across Spiritual Otherness in the Therapeutic Space, 39.

[19] For examples of relevant projects of the Arts in Interreligious Dialogue, see: https://www.clevelandmurals.org/the-interfaith-center.html, and https://ircf-frankfurt.de.