Richard Harries. The Image of Christ in Modern Art. Surrey: Ashgate, 2013, x + 176 pp., £19.99/$39.95 pbk.

In this insightful new survey, former bishop of Oxford Richard Harries presents the original view that the modern art movement has helped rather than hindered work connected to traditional Christian iconography.

The focus of Harries’ book is expansive. He considers images of Christ produced in Europe over the course of the past hundred years by artists of various religious affiliations. The work contains 82 illustrations spread over 156-pages of text, affording readers the opportunity to interpret each piece alongside Harries as they proceed through the text.

The opening chapter details the artistic climate in the early stages of the twentieth century. Harries asserts that this period was characterized by an acute awareness of the event that poet David Jones refers to simply as “The Break.” This rupture had two major effects:

First, the dominant cultural and religious ideology that had unified Europe for more than 1,000 years no longer existed. All that was left were fragmentary individual visions. Secondly, the world is now dominated by technology, so that the arts seem to be marginalized. They are of no obvious use in such a society, and their previous role as signs no longer has any widespread public resonance (5).

From Harries’ perspective, this situation posed both a challenge and an opportunity for artists wishing to relate to traditional Christian images. One the one hand, since Europe’s previously shared Christian narrative had been lost, their attempts to inhabit that narrative placed them on the fringes of the modern artistic vanguard. On the other hand, their marginalization “delivered them from the twin tyrannies of literalness and pastiche”(8). If they were to attain cultural relevance, they would have to find ways to depict traditional Christian images in new and arresting ways. The remainder of the book is devoted to showcasing artists who took up this challenge.

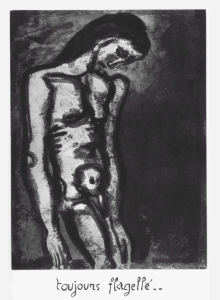

Chapters two and three consider art produced in the span between the first and second World Wars. After providing a brief discussion of the influence exerted by German expressionists, Harries directs his attention to two influential figures: Jacob Epstein and Georges Rouault. Both of these men worked at the forefront of the artistic advances of their time and drew on their respective faiths (Judaism for Epstein and Christianity for Rouault) to express visions of Christ that resonated with secular audiences who were largely disinterested in religion.

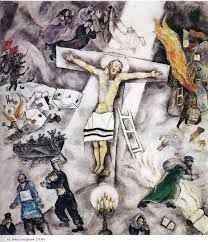

Harries then turns his attention to several individuals whose distinctive religious perspectives helped them construct fresh interpretations of traditional scenes in Jesus’ life. The most striking example that emerges in this section is Marc Chagall’s “White Crucifixion.” Harries highlights the way in which Chagall depicts Jesus as the paradigmatic Jewish martyr by surrounding him with stark images of brutality and oppressive restrictions forced upon Jews in the 1930s.

Chapters four through seven map the development of Christian iconography from the years immediately following World War II up to the present. Harries continues to treat individual artists (e.g. Graham Sutherland, John Reilly and Norman Adams), but weaves them into a wider discourse on the post-war recovery of confidence about placing art in sacred places. In doing so, he adds depth to his account of the role the image of Christ has played in the modern period. Harries shows that, for many artists, the challenge of depicting Christ in original ways was enjoined with a concern to integrate these images liturgically, sacramentally and theologically within particular churches.

The most impressive feature of Harries’ work is its lucid and inviting prose. This is a survey, but the individual accounts read like stories rather than collections of facts. His portrayals reveal a rare combination of aesthetic, theological and historical expertise that takes readers deep within the lives and works of the artists he canvasses. Consider, for example, Harries description of “Nativity” and his subsequent comments about the work’s artist Norman Adams:

‘Nativity’ provides an arresting perspective on the birth of Jesus, as it were looking down upon it through a flight of angels. It has a joyous cosmic dimension to it. It is not just the birth of any child, but an event that radiates out and sets worlds seen and unseen dancing in joyful circular movement. Adams was brought up in a household with no religious belief and the religious paintings in his grandparents’ house struck him as being about death and were something he feared. The religion he found his way into through art was a religion of life (114).

The fluidity of these individual descriptions, however, is not characteristic of the work’s aggregate structure. Some of the latter chapters feel like independent case studies rather than parts that contributing to an organic whole. Had Harries included transitional sections (as he does in chapters two and three) throughout the work, his audience would be left with a better picture of how work related to traditional Christian iconography developed during the last century. In spite of this minor criticism, Harries demonstrates his overall case admirably. He has provided a fresh and convincing argument that Christ has continued to live, and powerfully, in modern art.

Review by Eric Lewellen

Eric currently resides in St. Andrews with his wife Stephanie and his daughter Charlotte. At present, he is in the throes of completing his doctoral dissertation, which explores the relationship between the writings of Paul and the concept of natural law. In his free time, Eric can be found cooking, watching Survivor and agonizing over his various fantasy sports teams (sometimes simultaneously).