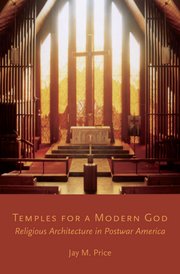

Jay M. Price, Temples for a Modern God: Religious Architecture in Postwar America, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, 288 pp. | Cloth $78/£50.

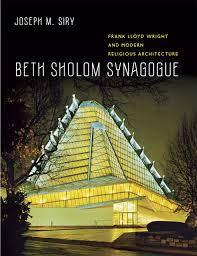

Joseph M. Siry, Beth Sholom Synagogue: Frank Lloyd Wright and Modern Religious Architecture, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011, 736 pp. | 10 color plates| 295 halftones| Cloth $70/£44.

Although Price’s book is the less substantial of the two works under review, it tries to cover a wider terrain, in effect the principles and practices underlying American church building between roughly 1945 and 1965. A period of considerable numerical growth for the churches, it was also a time of large expenditure on new buildings, averaging two-million dollars a day in the 1950s.

Although Price’s book is the less substantial of the two works under review, it tries to cover a wider terrain, in effect the principles and practices underlying American church building between roughly 1945 and 1965. A period of considerable numerical growth for the churches, it was also a time of large expenditure on new buildings, averaging two-million dollars a day in the 1950s.

Denominational journals (for example, F. R. Webber’s Lutheran Church Art, the Catholic Maurice Lavanoux’s Liturgical Arts or the Methodist Elbert Conover’s work through The Christian Herald) sought to move their communities beyond the auditorium or performance space to a new stress on sacrament and mystery. But there was resistance both from the more practically minded on church committees, and in the pews, from those who wanted more focus on pure function and the church as a social centre. This was a view that received major endorsement when the Church Architectural Guild of America (established in 1940) went on a tour of Europe in 1961 and found stress on utility, function and community given strong theological endorsement by an Englishman, Peter Hammond.

Revivalism of traditional styles and modernist mystery were then both attacked, as a form of social utility began to assume primary place, with synagogues also returning the bimah, or preaching platform, to a central position. Price has written what seems to me an outstanding history of the period that refuses easy glib summaries of the situation at the time. Instead, we meet a range of competing forces that were to be found in all branches of the Christian Church, including his own Missouri Synod denomination.

Although Siry writes more on Beth Sholom synagogue in Philadelphia (1953-9) than on any of Frank Lloyd Wright’s other religious commissions, the book is in effect a fine survey of the complete corpus, though with the strange exception that less is written on Wright’s Unity Temple in Chicago than on any other, perhaps because it is the one commonly given the most extensive treatment. Some unbuilt projects are also discussed, among them Wright’s only Episcopalian commission for a steel cathedral from the Rector of St Mark’s in the Bowery, W. M. Guthrie.

What characterizes all these commissions (with the likely exception of the last, Annunciation Orthodox church, Milwaukee, 1961) is the way in which Wright and the minister concerned shared a liberal conception of religion. Wright himself was a Unitarian, and indeed contributed to the cost of one of his Unitarian commissions (First Unitarian, Madison). Beth Sholom might seem an exception as it was built for the Conservative branch of Judaism that is a strong supporter of Zionism, but Rabbi Mortimer Cohen was in most ways strongly liberal and international in his outlook. He also supported the prophetic over the temple tradition, and that was one reason why he preferred the principal symbolism in the structure of the building to reflect Mount Sinai rather than the Temple and also chose a centralized bimah. While strongly opposed to anything in his buildings that might subordinate word to music, unlike architects of the International style Wright was in fact enthusiastic for symbolism.

Apart from the image of the mountain in Beth Sholom, also impressive was the way in which shafts of light projecting heavenwards are deployed instead of a spire in the 1939 Community Christian Church at Kansas. Siry’s survey not only enables us to inspect at first-hand the dialogue that took place between architect and client but also what it is about the buildings that made Wright such a great architect.

Reviews by the Revd Professor David Brown