~by James McCullough and Wes Vander Lugt

A few weeks ago, we launched a conversation on this blog about a definition of art. It is a project that emerges directly out of our teaching experience in the intersection of theology, ministry, and the arts. When interacting with people about the arts in non-academic settings, we have found that discussions quickly gravitate toward evaluations of art based on either personal meaningfulness or the classic, moralistic trinity: Language, Sex and Violence. In order to facilitate a more compelling and authentic encounter with art, we have found it important first to provide an understanding of art that was both heuristically simple while accurately describing what we encounter when engaging with art.

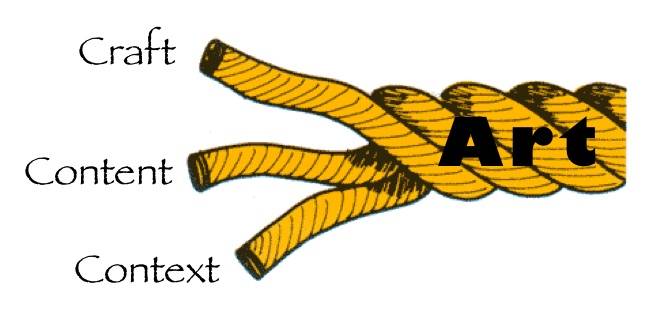

We suggested that art is fundamentally an exercise in communication involving three dimensions—craft, content, and context—and proposed a model that illustrated this dynamic. Based on feedback we received regarding our original model, we revised the visual to show craft, content, and context as three essential strands of art, inseparable yet distinct, as follows:

In this post, we seek to isolate one of those strands—craft—and discuss it in more detail. To begin, consider the fascinating line from Tom Stoppard’s play Artist Descending a Staircase:

In this post, we seek to isolate one of those strands—craft—and discuss it in more detail. To begin, consider the fascinating line from Tom Stoppard’s play Artist Descending a Staircase:

Skill without imagination is craftsmanship and gives us many useful objects such as wickerwork picnic baskets. Imagination without skill gives us modern art.

Even apart from its context in the play, we sense the sarcasm and overstatement, both about modern art and wickerwork picnic baskets. But the point remains: art is making something with both imagination and skill or craft. “Craft” is derived from the Greek techne, and refers to the actual process by which a “made thing” (a classic definition of art) is produced. Craftsmanship, therefore, is a disciplined, acquired skill that requires practice and is generally subject to the appraisal of those who know the craft: the “guild.” One essential strand of art, therefore, is the craft or skill of effectively producing or performing a particular work.

In addition, all art communicates in a particular way unique to that art form. Consequently, a large part of engaging with art is learning to understand the particular way an art work is communicating, whether through rhythm and rhyme, melody and timbre, movement and gesture, line and colour, or shape and form. Craft involves the effective usage and manipulation of these styles of communication. Great artists are great communicators in the language of their craft. Focusing on the strand of craft, therefore, serves the following objectives:

- Identifying craft as an essential strand of art enables us to limit the boundaries or what counts as art. Art is not simply anything we choose to call art, but something that is constituted by craft.

- Focusing on craft provides a means to engage with art on the level of skill and style. We do not intend to jettison emotional, visceral, or subjective responses to art, but do insist there is room for “informed opinion” about artistic craft, because art communicates something in a particular style with particular skills to an audience.

- Emphasizing craft enables us to adjudicate between the decorative-functional and the expressive-communicative. A work of art may revel in decorative gestures, but this does not prelude the presence of communication. This distinction may be blurred, but in general, art emerges through any act of crafted communication.

But where there is no craft, there is no art, or so we maintain. Imagination without craft gives us…well, gives us something less than art.

Thanks for your post, and for continuing this conversation. I appreciate your last sentence, “But where there is no craft, there is no art, or so we maintain. Imagination without craft gives us…well, gives us something less than art.” It is the separation of imagination from craft that I find so problematic in the work of most expression theorists (such as RG Collingwood).

Perhaps one theme that could be brought to the surface more is the relation between craft and tradition. By using the word ‘guild’ you suggest that tradition plays a part in craft, but you don’t really develop it. Both making and appreciating art could be seen as standing within a tradition, within a practiced way of performing both of those activities that have been handed down through history. Seen in terms of tradition, craft is personal and requires connoiseurship.

Your point about craft drawing limits or boundaries around art is well-taken, but I’m not sure how far it gets you. It may only allow you to say that ‘natural’ objects are excluded from the definition of art. So, basically anything that humans make could involve skill.

One thing that still bothers me about this whole communication metaphor is the other metaphor, ‘language’, that you associate with it. If learning a craft is simply a means of communication, then are you suggesting that once the viewer understands the priniciples behind the ‘style’ that they will then understand what the artist is communicating? It seems to me that an important aspect of craft is also learning ways to involve the participation of the audience, which seems to me is different from, or more than, “communicating something.”

Thanks once again for your interaction, Jim. Regarding craft and tradition, I think you are absolutely right that the craft of art is always situated within a tradition. In fact, this may clarify your next point, which is that art cannot simply be anything humans make with skill, because there is a sense in which it needs to be recognized as art within a particular tradition. Would that help to clarify?

In addition, I would resist along with you the goal of simply finding the principle behind the style in the act of engaging with art. If art is the weaving together of craft, content, and context, then these constituent elements cannot be pried apart as easily. In other words, it is not about the craft behind the content, but the craft woven together with the content and vice versa.

I resonate with your concern to avoid a uni-directional understanding of art as something communicating by an artist to an audience without participation. In fact, I am leaning toward “conversation” or “dialogue” as a better way of stating what art “does,” in that it invites others to participate in a process of creating meaning. This also averts the mistaken notion that an artist always intends to communicate one particular thing, or knows all the possible parameters of meaning.

Thanks again for the interaction, as it’s really helping us to clarify.

Wes, I don’t think that adding tradition will help you to put much firmer boundaries on art. For one thing, it seems that there is a lot of human making, or crafting, that is situated in a tradition, but is not normally considered art. For example, it could be argued that the PhD theses we are writing are works of craft within particular theological traditions. Perhaps more needs to be said about the institutions, organizations and people involved that get to decide what is labelled ‘art’?

So, if you resist the goal of finding the ‘principle behind the style in the act of engaging art,’ do you still think the metaphor ‘language’ is viable. For instance, you and James write “Craft involves the effective usage and manipulation of these styles of communication. Great artists are great communicators in the language of their craft.” This seems to suggest that the ‘language’ refers to ‘style,’ which itself appears really to be referring to basic elements involved in different kinds of arts. I am a little confused by this paragraph, as style often refers to something about the work of art that reflects the particular artist’s way of working (i.e. we might say that painting reminds me of Van Gogh’s style). So, I really think that the paragraph is saying that artists use the basic elements of their medium to communicate a message. Is this not also what you are resisting? How does weaving together craft, content and context modify the metaphor of ‘language’ that you are suggesting?

I think crafts on their own are not an emotional expression/form of communication. (i’m thinking of the handcut hardwood floors in a chapel in Nashville, or the craft of cabinetry) Comparing that to the bohemian art I see at our monthly gallery hop is telling: the floors seam to center on their use as an object, crafted by someone who cares deeply for them; the semi-experimental art at the gallery hop seems to center on the idea as it exists in the artists mind alone. The combination of the two approaches, in my mind, creates fine art.

Yes, I think it is important not to separate the functional and expressive, as we indicated in the post, because obviously art can involve both. This raises other very difficult questions, like where is the point where something becomes expressive enough to call it art instead of a useful object? I think linking this into the idea of a tradition and craft as a learned skill is a promising way forward.

Wes and Jim,

This post and your last provided a lost of food for thought on what exactly art is and what it is doing. I’ve really appreciated reading the conversation that has come out of it! One thing that I find particularly interesting is the way you engage the terms “art” and “craft.” This dichotomy is one that’s often made (by people like R.G. Collingwood, Howard Becker, etc) and I wonder how helpful most of the discussions actually are in the way they account for the relationship. That is, it seems like craft is often subsumed into the world of art or placed below it somehow. So we have craft conflated to just another, albeit slightly broader, version of art, or craft as something lesser than art (as in the quote you have from Stoppard). Do you think there is any way to get around these two extremes that both seem to favor art? I’m all for talking about craft in the way that art is made as you do here, however, I think you might equally talk about a theory of craft that is doing something slightly different, but no less valuable, than art. Since these terms are so crucial to your model, do you have any further thoughts on how exactly you see the relationship, both in similarity and difference, between art and craft?

Spoken like a true Craft! To be honest, I am just starting to think about these things myself, but I might phrase this as the relationship between ‘crafts’ (with an ‘s’) and ‘art’ because when we are talking about ‘craft,’ we are referring to the skill and style involved in all art. Regarding ‘crafts,’ my initial idea is that this is a particular tradition within art, that involves its own craft as it were, but I would appreciate any direction on this because I am sure you know much more about this than I do!

That clears things up a little. You definitely are right to talk about the “craft” or “skill” involved in making a piece of art. Unfortunately, we don’t have an abundance of nuanced terms to describe the matter. Howard Becker expresses this when he says, “As folk terms, ‘art’ and ‘craft’ refer to ambiguous conglomerations of organizational and stylistic traits and thus cannot be used as unequivocally as we would want to use them if they were scientific or critical concepts.” This is true, but I don’t think we should just give in to it. There has to be a better way! 🙂 My first guess would be to say that the reason we use “craft” in place of “skill” is because over time the craft tradition has become synonymous with skilled labor as opposed to artistic creation that takes into account both the object’s function and beauty. Until Enlightenment aesthetic theory took over the art world (a development in thought that began long before in the Renaissance…and a topic Jim Watkins would be much better to handle than I would), there weren’t such clear lines drawn between art and craft.

This is getting far removed from what you were originally talking about in your post, and I’m sorry for that. It just seemed to me that employing those terms might call for a little further explanation in order not to appear as though you are doing this same conflation or separation of art and craft hat I mentioned. Perhaps an exploration of the relationship between art and craft might be the topic for another post. 🙂 Thanks for opening up the discussion!

‘I’m all for talking about craft’.

Sheer arrogance.

So, in other words, not all crafts are art, but all art does require craft? Craft is a necessary component of art. I’ll buy that.

Now, when you’re talking about a work of art “communicating” something, do you mean that it really signifies something outside itself, or do you mean it in a different sense? It might be useful to distinguish between a “work of art,” which signifies something, and a “craft,” which does not. So, for example, a piece of music might signify an emotional state, or a painting may signify a landscape (leaving aside the question of whether it signifies something real or imaginary), whereas a chair or a ceramic vase usually do not, in themselves, signify anything. An art critic may well ask, “what is this painting about?” But no one would go to a furniture gallery and ask, “what is this armoire about?”

On the other hand, I wouldn’t want signification to become the sole standard by which we distinguish art from craft. At least, it would risk trivializing some admirable crafts while elevating kitsch art. It can’t be denied that a mediocre pop song does signify something, whereas a Chippendale tea table probably does not. Nevertheless, the tea table required more skill to create, and is probably the more admirable object.

Still, I think that we do intuitively distinguish “art” from “craft” partly on the basis of whether the object signifies.

Steve, thanks for bringing in the concept of signification. Could you say a little more about why you think a craft (such as an armoire) cannot signify? It seems to me that it could signify something. For example, I could make a yellow armoire for my wife (yellow is her favorite color) to signify my love for her. Does this then ‘make’ the armoire art?

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/episteme-techne/#2

Jim: I think it may be more beneficial to talk about craft as skill and style rather than language, especially since a communicative event is much more than language. Basically, a work of art offers an opportunity for a communicative exchange, which involves craft, content, and context.

Steve: I do think that “crafts” can be “about” something, because even though crafts may be functional, they are also a communicative events of some kind.

Paul: thanks for the link to the arts. I would have to study this more to comment on how our articulation of craft corresponds to Platonic and Aristotelian perspectives, but I know they would diverge at points.

Fascinating thread of conversation folks…

One of the prime areas of confusion over the past hundred years in art theory (and practice) has been brought about by what I’d call an epistemic conceit — the notion that “craft” is a lesser entity and that “art” is somehow automatically more significant. As this thread shows, the two are inextricably intertwined, and therefore the attempt to sunder them is at best silly, at worst sinister. Stoppard’s larger positive point, apart from the traditional distinction of craft and art, is to celebrate the unified thing whenever we encounter it. So much of what we’re given in art, post-WWI, shows evidence of the rupture of the two. Those inclined toward fine craft have tended to shy away from “modern art”, and those inclined toward the conceptual turn have tended to de-emphasize craft, often to an absurd degree. But what is apparent all round is the confusion — confusion over what is fitting, what is truly meaning-filled, what is beautiful and enobling. Etienne Gilson claims that art is, properly understood, a mode of being — not a form or knowledge, language, or communication. He further claims that this mode of being has as its proper object “the beautiful”. I realize that this complicates the conversation and may be a non-starter, but if Gilson is right a lot of the foregoing conversation could simply be jettisoned. If art is a mode of being (which of course takes up techne, knowledge, language, communication, etc) then opposing or trying to evaluate the relative merits of craft vs art becomes meaningless.

…another couple of thoughts at the risk of overstaying my welcome…

Gilson, in The Arts of the Beautiful, discusses the widespread confusion I mentioned above, and he equates it with the apriori assumption that art is a form of knowledge. If that were the case, he says, then to merely think a work of art would be to achieve it. And DuChamps unleashed just this — namely, the conceptual turn that equates the work of art with an idea or notion in the mind of the artist. Thus, I could place a public urinal on a pedestal and declare it a work of art — simply because I have decided to think it thus. This rules out craft entirely. (That is, it rules out craft on the part of the artist. But the designer of the urinal has to exercise craft in its making.)

Gilson goes on in the rest of his essay to elaborate a refreshingly earthy exposition of his definition of art — namely, that it is a properly basic human activity entirely wrapped up in “making” in facture. His simple formula: “Man performs different kinds of acts: he is, he knows, he does, and he makes.” So art is a basic form of human action that can obviously involve knowledge or communication or other actions, but it is properly basic and foundational. I personally find this very satisfying, and it reminds me of Wm Carlos Williams’ aphorism that I have been using lately to clarify my own thinking: “No ideas, but in things.” Making is a good thing, and it takes art and it takes craft.

Thanks for your comments, Bruce, and I resonate with your concern (and Gilson’s) not to reduce art to an idea. I agree that art is an action, but I think what James and I are claiming is that this action has some kind of craft, content and context that makes sense of the action.

If Gilson is right about art as a mode of being, how would you best instruct others how to engage with art, whether the enduring classics or the popular art that pours out of our speakers and streams on our computers?

Wes – I honestly don’t think that art can be “taught”. (Though of course, certain media, skills, historic examples, periods, and theories can be.) Art, as a fundamental way of being human and acting in the world, is so basic that I don’t think it really needs to be taught so much as given place. Every culture in every epoch of human history has had art at the center alongside religion and livelihood. Perhaps it is taught in the same way that faith is taught — more by example than by indoctrination. I personally have a problem with much modern art theory because it resembles that doctrinaire religion that is so toxic to faith. On the classical vs pop culture I’d only say that this distinction has always been there. Entertainment and aspiration exist alongside each other in all cultures. They’re not mutually exclusive, but they are distinguishable, and perhaps the old “fine arts vs. applied arts” distinction is similar. I think that is where Stoppard was coming from…

Another thing that occurred to me is your use of the word ‘skill’ and the way you oppose it to imagination. It could be argued that skill already implies imagination, and that skill without imagination is not skill at all. For example, skills are always teleological in the sense that they have an end in mind. I want to bake a birthday cake, and so I use my (albeit limited) skills as a baker to do so. I have to imagine the end result in order to exercise my baking skills. Without imagining the end there would be no point in exercising the skills. Examples of activities that already have the end imagined for us would include things like ‘paint by numbers’ and it is precisely these sorts of activities that we hesitate to label ‘skillful.’ Or it might be helpful to juxtapose skillful activities to accidental activities. If I just randomly start throwing flour, eggs, butter etc. around in the kitchen with no purpose in mind, but I somehow accidentally arrive at a birthday cake, then I would hesitate to describe the making of the cake as skillful. And the reason I don’t want to call it skillful is that I did not use my imagination. So, these arguments suggest that there is no such thing as skill without imagination, and so to say that art is making something with both imagination and skill is actually redundant.

This is a truly thought provoking post, and it appears that there is also a great discussion going on here. I have to agree that content, craft, and context are distinct elements that when tied together produces art. I still have to read the rest of the comments in order to participate well in the discussion. But, let me commend you again for your insights.

Thanks, John. And I welcome any other comments you might have. You will also notice that we have another recent post on the content of art. And or post on the context of art will be coming out next Friday.