‘We are a ferocious animal. We humans are terrible animals. Here in Europe, in Africa, in South America, everywhere. We are extremely violent. Our history is a history of wars. It’s an endless story, a story of repression, a tale of madness.’

These words chill the soul. They are a nursery rhyme compared to the images that gave birth to them.

Sebastião Salgado, one of the world’s most celebrated photographers, uttered these words during the filming of The Salt of the Earth (2014), a film about his life and work. Written and directed by Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, The Salt of the Earth spans just about the entire oeuvre of Salgado’s photographic career. Appropriately, the focus is on Salgado’s images, alive in their own right. They are brought to another level of life as he narrates the story behind them. The film, like Salgado’s images, is stunning, dramatic, dynamic, beautiful, devastating.

It is obvious when you see Salgado’s work that he cares deeply for individual people and our species as a whole. This is evident through the range of his work that focuses both on a celebration of the fullness regarding diversity of human culture as well as the documentation of the depths of human cruelty.

There is an urgency and an immersive quality to Salgado’s photography. He will often invest years of his life into a single project that explores just one theme. Salgado enters into a place, sometimes for months at a time, in order to bear witness to the unspeakable suffering of our fellow humans. Who has words for what his eyes have seen? Only images and tears, seared into the memory that cannot be washed away.

There is an urgency and an immersive quality to Salgado’s photography. He will often invest years of his life into a single project that explores just one theme. Salgado enters into a place, sometimes for months at a time, in order to bear witness to the unspeakable suffering of our fellow humans. Who has words for what his eyes have seen? Only images and tears, seared into the memory that cannot be washed away.

‘How many times did I lay my cameras down to cry over what I’d seen’ he says at one point during the film. How could he ever pick it back up again, I wonder? There is an indomitable urgency to how he lived out vocation, bringing attention to what was happening in the world, providing a voice to the voiceless with his arresting images.

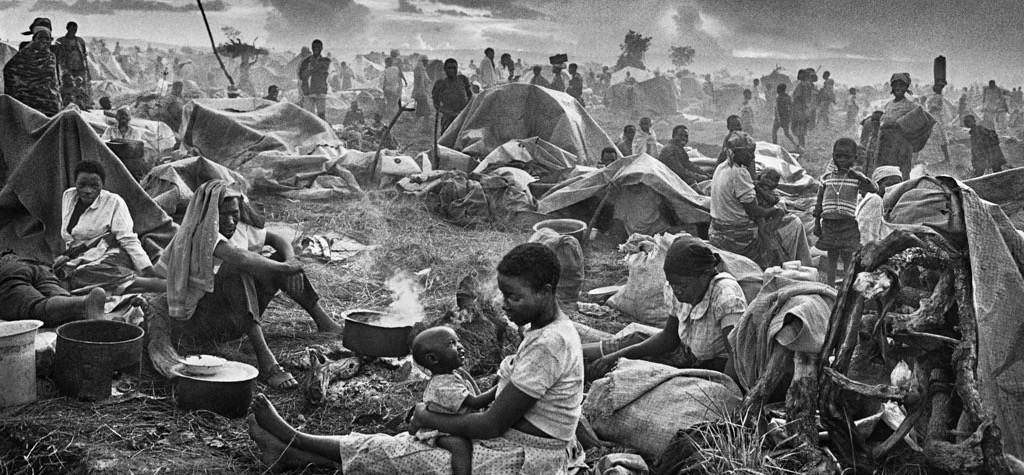

Salgado spent the first twenty or so years of his photographic career documenting the plight of the human struggle across the globe. He was not a man unacquainted with suffering, but the Rwandan genocide eventually broke him. Salgado was in Rwanda while working on Migrations (1992-1999), his project focused on mass migrations and refugee crises. Two decades of capturing suffering through a camera lens eventually caught up to him.

Salgado was wrecked by what he witnessed: bodies filled with bullets or torn open by bits of grenades or hacked apart by machetes, all strewn about the streets; the desiccated, desecrated remains of people who fled to a church sanctuary seeking safe haven; the bones of school children in a classroom, all murdered, with the day’s lesson still chalked on the board. These are haunting images.

Perhaps the most jarring photos in the film are from the Goma region of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Some two million Hutu refugees fled Rwanda to the DRC in July 1994. Twelve to fifteen thousand people died every day from infectious diseases like cholera. They simply could not bury all the dead so the French army sent bulldozers. Salgado captures a series of images of bulldozers dumping dozens of bodies at a time onto the ground and covering them with earth.

About this series of photos, Salgado states matter-of-factly: ‘Everyone should see these images to see how terrible our species is.’ The images cannot be unseen.

Recounting his experiencing in Rwanda, he comments: “When I left there, I no longer believed in anything, in any salvation for the human species. You couldn’t survive such a thing. We didn’t deserve to live. No one deserved to live.”

I think many of us are uncomfortable with this kind of grim, pessimistic indictment of our species. It seems that the more popular view is that most people, by nature, are actually decent, even good. Or, at the very least, if human nature is corrupt, society provides the ballast to save us from ourselves. Salgado provides evidence to the contrary. He has peered into the heart of darkness and taken pictures. His images expose the error of both views; as it turns out, neither Hobbes nor Rousseau got us right altogether.

Salagado’s images give credence to some of the passages in the Scriptures that we might normally find embarrassing in light of the so-called progress of our species. I immediately think of Genesis 6:5, the antediluvian passage where we read that, ‘The LORD saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every intention of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually.’ Jeremiah 17:9 also comes to mind: ‘The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick; who can understand it?’

The film corroborates the bleak description of the fallen human condition found in the Scriptures. It should go without saying that this is tragic; it is not cause for celebration. I chose to write this meditation on the film because, despite the cruelty and inhumanity it portrays, it also reminds us that humans are the salt of the earth. The film ends with hope, perhaps the virtue most needed today.

When Salgado left Rwanda, his soul was sick. The blood of our kin issued an indictment from the ground and Salgado heard the cries. He was a man poisoned by the inhumanity of our species. He questioned his life’s work bearing witness to the human condition. The only thing left for him to do was to return to his childhood farm in Aimorés, Brazil which was connected to the Mata Atlantica, the Atlantic Rainforest.

Physically and spiritually broken and despairing, Salgado returned home to a land that mirrored himself. Land that was once a vibrant eco-system had become a wasteland. The family property was once fifty-percent rainforest. Over the years, the land was decimated and only one-percent of the rainforest remained. The forest was cut down, the springs dried up, severe droughts came and the earth was left barren, unable to sustain the abundant flora and fauna that once called the place home. What Salgado did next, he calls a full-blown miracle.

Physically and spiritually broken and despairing, Salgado returned home to a land that mirrored himself. Land that was once a vibrant eco-system had become a wasteland. The family property was once fifty-percent rainforest. Over the years, the land was decimated and only one-percent of the rainforest remained. The forest was cut down, the springs dried up, severe droughts came and the earth was left barren, unable to sustain the abundant flora and fauna that once called the place home. What Salgado did next, he calls a full-blown miracle.

Salgado and his wife, Lélia, decided to replant the rainforest. Over the span of ten years, they planted over 2.5 million trees of about 200 species and restored roughly 1500 acres of rainforest. They restored the earth and rebuilt the eco-system. The land has become a national park and is the site of the Instituto Terra, the organization they founded to help with reforestation and conservation around the globe. Revitalizing the earth revitalized his soul.

The land healed his despair, breathed new life into his dry bones and resurrected his vocation as a photographer. Salgado’s imagination was renewed and the experience gave birth to a new photographic project called Genesis. Whether he is aware of it or not, Salgado is tapping into the original and enduring human vocation from the creation account in the first two chapters of Genesis. Rather than destroying creation, humans could participate in cultivating and renewing creation.

I do not want to baptize Salagado’s work inappropriately. I have no idea if Sebastião Salgado is a man of faith. That is not the point here. In a world dominated by stubborn violence, the hypnosis of shiny things and abject indifference, Salgado’s work goes with the grain of the universe. Salgado is working to set the world to rights. His is a story worth telling because its bears the marks of the story all humans are created to live as the salt of the earth.

Banner Image: ‘Rwandan refugees in a refugee camp in Benako, Tanzania in 1994.’ (Sebastião Salgado/ Amazonas Images)