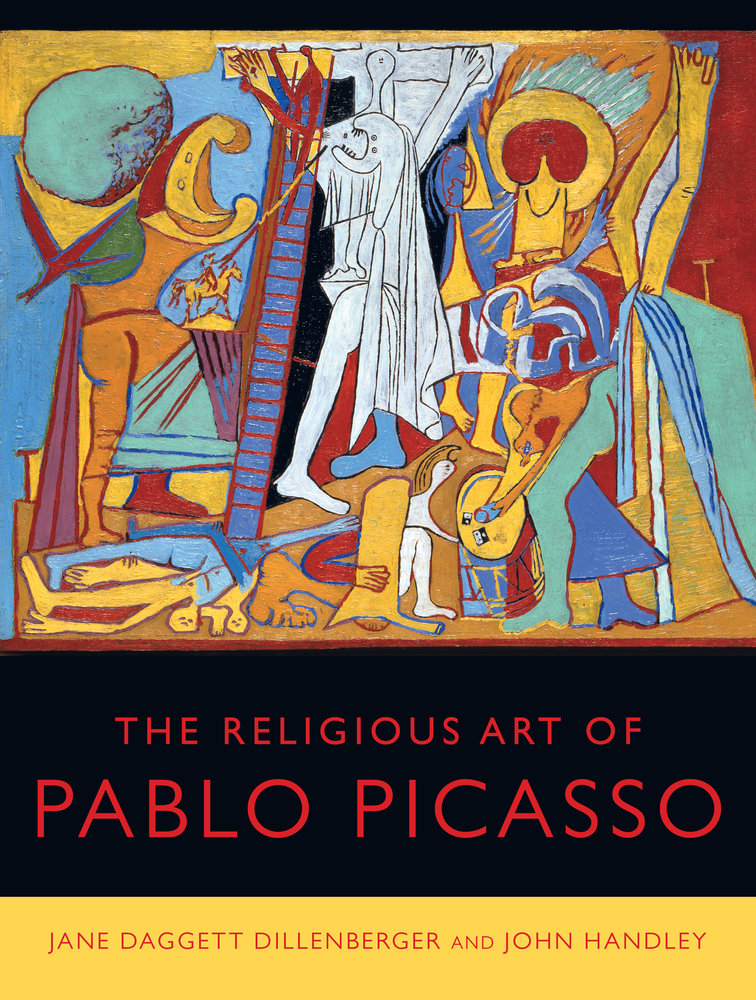

Jane Dagget Dillenberger and John Handley, The Religious Art of Pablo Picasso. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014, xii + 108 pp., £27.95/$39.95 cloth.

Jane Dagget Dillenberger and John Handley, The Religious Art of Pablo Picasso. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014, xii + 108 pp., £27.95/$39.95 cloth.

The book presented here, written with my friend and colleague John Handley, explores the religious art of Pablo Picasso–a subject that is sure to surprise many. Over several cups of tea we decided to write this book–and we did and this is it.

Dillenberger, “Preface,” xii.

And so it begins. Straightforward and matter-of-fact. In fact, one might wish that these cups of tea and the resulting decision to write this book had come sooner. In any case, I’m glad to have (and to hold) this lovely, slender volume now. It’s a book for libraries and studies, yes, but also for living room tables and bedroom nightstands (or wherever else you stash books for casual reading).

The book has two aims: 1) to draw our attention to Picasso’s religious imagery, and 2) to encourage us to consider the religious implications of his so-called secular work. In both cases I couldn’t help but think of a favorite essay by David Brown, one that I’ve quoted here on Transpositions before, and here quote again:

A constant temptation among Christians when looking at art or music is to view their role, when legitimate, as at most illustrative, confirming or deepening faith but never challenging or subverting it. It is therefore hardly surprising that there is so much bad Christian art and music around, if even the more informed among us want to keep their influence in a safe pair of Christian hands, such as Rembrandt or Rouault in art, Bach or Bruckner in music. The more liberal minded, in spreading the net more widely, may believe themselves immune from such criticism, but often the same fault is still there: art seen as merely illustrative of what is already believed on other grounds…. But in the main I want through the use of specific examples to encourage readers to reflect for themselves. Jesus, if I am right, learnt from a pagan; might not we also?[1]

The book includes five chapters: 1) The Crucifixion, 2) The Early Years, 3) Picasso and the Church, 4) Guernica: Ultimate Concern, and 5) The Corrida and the Sketchbooks of the 1950s. What follows is a brief summary of these chapters.

The first chapter draws our attention to “a unique painting that has received little attention … a small surrealist work, The Crucifixion, painted by Picasso in 1930.”[p. 1] Having already presented this image on the cover, the authors begin with Picasso’s early work before turning to several preparatory drawings, and then to the work itself. Most interesting to my mind and imagination, however, was the 1932 series of drawings after Grünewald, “bone-like forms against a lunar landscape,”[p. 16] with which the chapter concludes. In the second chapter, we return to Picasso’s early work, and this to observe that “Picasso would again and again return to the themes of Christianity and, more specifically, the crucified Christ.”[p. 21] Chapter 3, “Picasso and the Church,” focuses on his sculpture Man with a Lamb, as well as his War and Peace murals in the chapel of the Château-Musée de Vallauris, “The Temple of Peace.” The authors conclude that in the latter, “Picasso missed one great opportunity that could have resulted in a lovely, meditative space…. Man with a Lamb could have brought to the chapel a deeper sense of the meaning of the fight between evil and good, war and peace.”[p. 55] If Man with a Lamb was in Chapter 3 judged to be a more successful depiction of peace, Guernica is in Chapter 4 judged to be a more successful depiction of war. Regarding the former, but equally applicable to the latter, Dillenberger and Handley note: “Though the title does not suggest religious subject matter, the conception and content … are rooted in Western religious consciousness.”[p. 41] Put differently, these works are what Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Picasso’s friend and dealer, called “an introvert art after six centuries of extrovert.“[p. 60] Teasing this out, the authors cite the 4th century sculpture The Good Shepherd as visual precedent for Man with a Lamb, and then the words of Paul Tillich with reference to Guernica which he thought “the best present-day Protestant religious picture…. because it shows the human situation without any cover.”[p. 61] In the fifth and final chapter, the authors discuss “[t]he two themes of the Crucifixion and the corrida [i.e., bullfight], united by Picasso” in a group of drawings.[p. 73]

The book is a quick and enjoyable read filled with full-color reproductions, encouraging readers to mosey rather than rush their way through its pages. While selective, its essays might serve as a sort of introduction to the painter from a religious perspective. The Religious Art of Pablo Picasso makes an important contribution, and belongs (next to Dillenberger’s The Religious Art of Andy Warhol) on the shelves of anyone interested in 20th century art, theology/art studies, or the possibility of a natural theology of the arts.

[1] David Brown, “The Glory of God Revealed in Art and Music: Learning from Pagans,” in Celebrating Creation: Affirming Catholicism and the Revelation of God’s Glory, ed. Mark Chapman (London: Darton, Longman and Todd), 44-45.

Review by Christopher R. Brewer