During a recent visit with my in-laws, my two and a half year old daughter, at the end of a very hot day, made a disconcerting discovery. In an attempt to escape the day’s sweltering heat (41˚C), my wife and I decided we should all bed down in my in-laws’ basement. As I was getting my daughter settled in for the night, all was going well until, suddenly, she got an odd, disturbed look on her face and pointed toward the nearby bookshelves. We followed her outstretched finger and saw the source of her consternation: clown face bookends.

Now, there are a multitude of aesthetic sensibilities that these bookends might have offended in my daughter, but I doubt such offense prompted her to request the immediate removal of the dubious decor. Something in the nature of those clown faces elicited the response. And this is what I want to explore: the often unsettling nature of the clown.

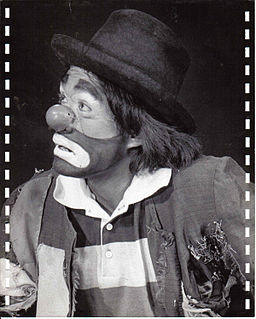

Before I go any further, let it be known that I have friends who are (or were) clowns. I myself have been paid to act ‘clownishly’. I also recognize that at least one major corporation considers the clown to be so far from troubling they employ one as a corporate mascot. I mention these things because clowns are often unfairly lumped together and become the target of thoughtless derision. While I hope not to engage in unwarranted stereotyping, I will (due to considerations of space) need to make some generalizations, beginning with a loose definition of a clown: a clown is typically a comic performer who presents an exaggerated version of a person by way of stylised movement, gaudy costuming and bold facial makeup. In what follows, I’d like to primarily focus on the clown face.

A clown face is designed to be ‘read’ from a great distance. Ironically, the very elements that allow a far-removed audience to engage with and enjoy a clown (red nose, painted on expression, etc.) are the very same qualities that can be unnerving up close. Away from the lights of the stage and the ring of the circus, the painted face of a clown can seem more grotesque than humorous. Clowns, particularly when encountered up close, are perceived as being a relational anomaly, there is an ‘otherness’ about them, and I believe this ‘otherness’ is what provokes a response of discomfort, even fear.

I think light can be shed on this response by way of biblical theological anthropology. Scripture indicates people are created in the image of God. Given the triune nature of God, this means, if nothing else, people are created to be in relationship: with God and with others. One of the primary means of establishing relationships with others is by way of facial expression. All of us, from the day we are born, attempt to glean information about people by studying their faces. Given that a clown face is akin to a mask, our ability to discover something true about the person behind the mask is called into question. This challenges our ability to form a relationship and imbues the clown with a sense of mystery that can be menacing.

Who, we wonder, is this person really? When we see the painted smile, but know that the clown is actually sad, we are made uneasy by the discrepancy. In this way, a clown face can also be seen as opposing revelation. The makeup can serve to prevent the kind of contextual embodied expression that often lies at the heart of building trust with others.

It’s commonly said that all of us wear various ‘masks’ every day. However, these masks are virtual and we aren’t as skilled as we think we are at masking our true nature before others. A clown, on the other hand, can effectively hide behind an actual, painted on mask, as well as an obfuscating array of clothes and props.

What do you think? Do clown faces elicit a response of fear in you? Do you think there are theological reasons for this response?

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Commedia dell’Arte included a stock clown character (Pierrot) and in opera of the nineteenth-century he had many appearances. Pierrot was the comedic element of the play or opera but as the character evolved composers began to unmask Pierrot for his true nature. There began to be cracks in the comedic function of the Pierrot character with the 1892 two act opera Pagliacci by Rugger Leoncavallo where the clown murders his own wife. Then there is that seminal atonal work by Schoenberg (celebrating the 100th anniversary of its premiere this year) Pierrot Lunaire (Moondrunk Clown). Schoenberg’s Pierrot is stripped of his buffoonish aspects and is instead shown as a dark figure full of lustful desires and exposing the inner man behind the mask for what he truly is. This is a theological statement I am interested in exploring in this work but also reminds me of John 2:25 where Jesus can see through our masks because, “He did not need man’s testimony about man, for he knew what was in a man.” The music of the Schoenberg work matches the description of this dark Pierrot moving all over the place, no longer matching the jovial sounding music which was associated with Pierrot in the past (http://youtu.be/rkSMwKFKbyw).

In my own clowning, I use only a red-nose rather than any clown make-up. This has the advantage of allowing me to quickly take off this “smallest of masks” (per LeCoq) to expose my face if my audience seem too disturbed by my appearance. The play between me and not-me becomes even more exaggerated, highlighting the third possibility of not-not-me (per Schechner). This makes me wonder if the problem is not the mask, but the refusal to acknowledge how we are putting on a persona and refusing real relationship with others on a personal level. My intent in doing what I call socio-pathetic clowning is to engage others, especially strangers, in interactive play in order to make room for genuine relationship, even if only momentary. I hope to play a fool for Christ, risking low status means for high status ends.