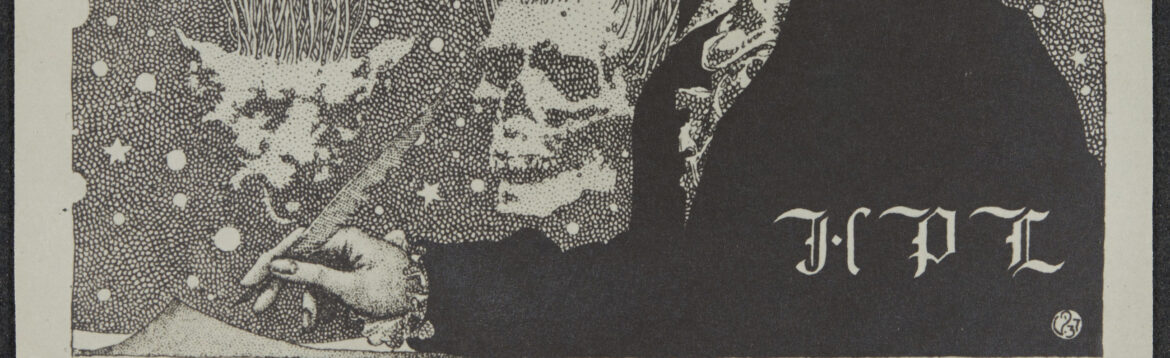

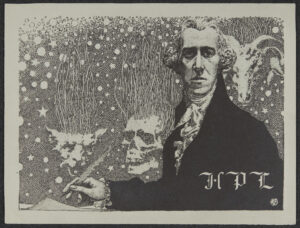

A prevailing theme within the canon of Christian Scripture is the meeting of God and humanity. On the one hand is a Being of incalculable power, intelligence, and glory, on the other is mortal man. Despite the chasm between these parties, the Scriptures present a complex and ultimately loving dynamic between God as Creator and humanity as the peak of creation. This dynamic is largely inverted within the genre of cosmic horror, as seen in the work of H.P. Lovecraft. The benevolent Creator is replaced with deeply malevolent or, perhaps worse, apathetic entities whose very visages drive some to madness. Humanity is reduced to specks of dust in a vast, dark world. In both instances, though, humanity stands in the presence of an Other beyond all comprehension.

We might say there is a fine line to draw between the experience of holiness and horror, but their similarities make their differences only more glaring. Though this final contrast may incline us to think these kinds of texts—Scripture and horror—serve different purposes, it is possible to see how the experience of existential terror inspired by a hostile and uncaring universe in cosmic horror may inspire us to better understand the divine within the biblical landscape.

In the realm of human imagination, it is that which lies beyond our grasp that most discomforts us. These unknowns can force us to reconsider the assumptions we daily live with, as well as our dearest securities and confidences. Within classical philosophy, the infinite was among these great “Others” or unknowns beyond human fathoming. The magnitude of infinity led to its status as a ‘negative concept; as a result of its lack of definition’.1 As rational actors, we enjoy categorizing information, but when something fails to be contained within the comfortable limits of reason, it has a disquieting effect. Due to its inability to be defined, humanity tends to respond to the infinite—or seemingly infinite—with fear and a diminished sense of self, ‘The infinite is where reason goes astray and is annulled. […] beyond these limits (of our known reality)—in that impossible and corrupting “beyond”—monsters lurk’.2 The infinite is an expression, perhaps the purest form, of the unknown. However, debate has been raised as to whether or not H.P. Lovecraft’s emphasis was merely on the unknown or the unknowable.3 What is unknown is shrouded in darkness, allowing our minds to conjure horrors dwelling in the shadows, but what is unknown may someday be known. For an item of knowledge to be truly unknowable, it must break from all comprehensible standards of rationality or at least stretch beyond comfort.

It is not difficult to imagine entities of fear and loathing inhabiting the furthest reaches of the imagination, but there is also an element of awe in the idea of the cosmic that must be taken into account. In the case of deep space, there is a sense of awe even when there is also a sense of fear: “Cosmic fear for Lovecraft is an exhilarating mixture of fear, moral revulsion, and wonder.”4 In the Bible, responses to the presence of God often share these three traits. The biblical examples are distinct, though, because moral revulsion is not directed outward but inward; it is flipped in that the person standing before God becomes revolted with their own moral failings. Within the Book of Job, for example, the titular figure eventually comes to stand in the presence of God after seeking an answer to his sufferings. God responds by recalling the vastness of creation and the complexity of all that surrounds us, depicting Job as a small speck in a long history. This is not done to diminish Job’s value—God has still come to speak with him directly—but to display the chasm of difference between an almighty, infinite God and a lone man questioning his sufferings.

As the writer of Ecclesiastes states, the Lord ‘has put eternity into man’s heart, yet so that he cannot find out what God has done from the beginning to the end’.5 Job is confronted with the unknowable and the infinite and, despite his own righteousness, he cannot stand his ground. Job repents of his doubt and admits his own ignorance: ‘Therefore I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know’.6 Fear and awe intertwine in the presence of the infinite Other, but there is a care and intimacy to their interaction, resulting in greater blessings for Job afterwards. Job repents ‘in dust and ashes’ after this communion, recognizing his own limitations in the face of his Creator.7 Despite the otherness of God, there is a relationship established between him and humanity. In his fullness, he is unknowable, yet he remains largely personal in his approach. We do not see malevolence or apathy in their relationship, and this provides a helpful guide by which we can connect the holiness of God with the horror of cosmic powers while continuing to recognize their distinction.

Within Lovecraft’s short story ‘Dagon’, the vague humanoid resemblance of the Others is part of the narrator’s terror. The narrator is confronted with artistic depictions of beings beyond his imagination, but the similarity in form between himself and these Others makes them only more shocking and uncanny, ‘Grotesque beyond the imagination of a Poe or a Bulwer, they were damnably human in general outline […] but in a moment [I] decided that they were merely the imaginary gods of some primitive fishing or seafaring tribe […]’.8 The only rational response to these drawings was for the narrator to assume they were fictions, despite previously claiming they fell outside even the imaginations of great writers. It was a desperate attempt to cling to his comfortable prior ignorance, one which disintegrates when he sees one of the creatures with his own eyes, ‘Vast, Polyphemus-like, and loathsome, it darted like a stupendous monster of nightmares to the monolith […] it bowed its hideous head and gave vent to certain measured sounds. I think I went mad then’.9 Not only is the narrator confronted by the reality of these Others, but he is also miniscule in comparison. The creatures he sees are not infinite, but are still beyond the comfortable limits of his mind. The horrific size and appearance mixed with disturbing vocalizations are enough to drive him to insanity and a morphine addiction.10

When we consider this story alongside biblical encounters of the divine, it seems possible that interactions with God—the biblical Other—fail to produce madness only due to divine mercy. This mercy, as well as divine care for humanity, is a distinguishing factor when seeking connections between holiness and horror. The Others of Lovecraft’s mythos are either malevolent or apathetic towards humanity. Additionally, the uncanny nature of the Others prevents any sympathies or relatability from emerging in cosmic horror. In Lovecraft, any similarities are the results of mockery or accident at the hands of superior races and become a source of hostility and revulsion.11 The cosmic Other in Lovecraft tends to reveal a lack of meaning in our lives, because ‘the subject suffers from a violation of its sense of self, but it is graced with no consolatory understanding of the human condition to mollify its fragmented psyche’.12 Such meetings in Lovecraft’s fiction obliterate the bastion of significance we may have possessed in our rational minds.

This is a fundamental difference between cosmic horror and the Bible. We learn in Genesis 1 that humanity was created in the image of God, granting us significance despite our smallness. This feeling of insignificance may still be present when one is confronted with the presence of God in the Bible, but it is a feeling tempered by the understanding that humanity was made intentionally by God. This establishes a kinship beyond mere form and presents the relationship between humanity and God as one of parental care. The nature of God in the truest sense may be unknowable, but this familial connection allows him to be known as he relates to us. In contrast, the revelation of such familial relations in Lovecraft’s work only causes greater horror or insanity, such as in The Shadow over Innsmouth, when the main character discovers that he is descended from the Deep Ones.13 A discovery of this sort is that of forbidden knowledge, a hidden knowledge discovered at the expense of one’s humanity.

In this instance, the increase of knowledge leads to certain doom as we uncover hidden monstrosities, but within the biblical landscape knowledge brings one closer to salvation as it reveals the nature of God’s work. Within the Bible this knowledge comes as revelation from God so that he might be known. An example of this is seen in Exodus as Moses is approached by God through the burning bush.

Then [the Lord] said, ‘Do not come near; take your sandals off your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.’ And he said, ‘I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.’ And Moses hid his face, for he was afraid to look at God.14

God bridges the gap between himself and Moses by first introducing himself through the names of Moses’s ancestors. It establishes a personal nature to God despite the otherness of the encounter. The cosmic nature is brought out as God reveals his proper name further along in the discussion in Exodus 3:14, ‘God said to Moses, “I Am Who I Am.”’ The simple statement displays God as “being” without qualification. The statement ends at the very fact of his existence. Such a reality is beyond proper understanding and could not be more othered from human experience. The mere presence of God marks the ground as holy, or set apart. The opposite is true of the Others within Lovecraft as the ground marked by them becomes disturbing, uncanny and blasphemous.

In the end, as humanity encounters the Other, a change must take place. Worldviews must shift and one’s perception of reality is altered to encompass knowledge of the previously unknown. Life cannot continue in blissful ignorance. Though fear is an inevitable feature of such revelations, our human curiosity brings an equal sense of awe. The results of these revelations, ending in death or madness, or else relationship with a divine Creator, display our own limited abilities in a vast world. Within the scope of cosmic horror, humanity is helpless to save itself from the dark powers residing in the abyss. In the biblical landscape, humanity is helpless to save itself but finds a guardian in its Creator. There is no benevolence at the end of space and time for Lovecraft, but there is no darkness at the summit in the biblical landscape. There is no need to fear.