Recently, there has been much controversy about AI-generated ‘art,’ resulting from the recent developments in Generative Neural Networks (GANs)[1] and subsequently a popularization of image generators based on Machine Learning algorithms, such as DALL-E from OpenAI.[2] A number of philosophical criticisms have been raised regarding the ethics of AI-generated art.[3] For example, some have questioned whether the computer could be credited as the author of the artwork,[4] and others whether whatever is produced by AI could even be regarded as art in the first place.[5] However, I do not wish to directly answer these questions here; instead, I will discuss a parallel question of whether an AI can paint an icon.

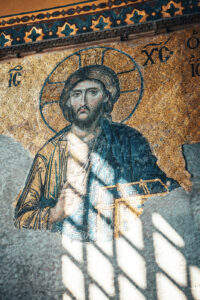

To be more specific, I am not asking if Machine Learning (ML) algorithms have the technical ability to generate something that looks plausibly like an icon, one that even has the potential to evoke devotional sentiments to the viewer. I have no doubts that a specifically designed GAN trained on an iconography dataset could achieve this in the near future. Rather, my question is of a more metaphysical and religious nature: would the ‘icon’ generated by such an algorithm actually be a proper icon? The answer lies in understanding what a ‘proper’ icon is and how it is made. I believe that attempting to answer this question in reference to the iconoclastic controversy can shed a light on the more fundamental questions regarding AI and the essence of religious art.

To be more specific, I am not asking if Machine Learning (ML) algorithms have the technical ability to generate something that looks plausibly like an icon, one that even has the potential to evoke devotional sentiments to the viewer. I have no doubts that a specifically designed GAN trained on an iconography dataset could achieve this in the near future. Rather, my question is of a more metaphysical and religious nature: would the ‘icon’ generated by such an algorithm actually be a proper icon? The answer lies in understanding what a ‘proper’ icon is and how it is made. I believe that attempting to answer this question in reference to the iconoclastic controversy can shed a light on the more fundamental questions regarding AI and the essence of religious art.

I will argue that, through the lens of the iconoclast controversy of the eighth and ninth centuries, any ‘icon’ generated by a ML algorithm would be inherently idolatrous since the relationship between the image and the archetype would be severed.[6] That is, although the works produced by a human iconographer and an AI ‘iconographer’ may be outwardly similar, inwardly they would be radically different due to the disparity in the process of their creation. A human iconographer faithfully contemplates and depicts the archetype; an AI abandons the archetype and merely replicates its images. And if this is so in the case of iconography, it implies a danger of idolatry in involving AI in religious art or employing it for religious purposes.[7]

The iconoclast controversy is a particularly relevant discourse for reflecting on the question of the use of AI in religious art because it was essentially a debate regarding the relationship between the image and its archetype. The icon (εἰκών) is an image of an archetype (Christ, Theotokos, or Saints), and this is analogous with the relationships of natural image that the Son has to the Father[8] and the image of imitation that humankind has to God.[9] As St. Theodore the Studite explains,

Every image has a relation to its archetype; the natural image has a natural relation, while the artificial image has an artificial relation. The natural image is identical both in essence and in likeness with that of which it bears the imprint … The artificial image is the same as its archetype in likeness, but different in essence, like Christ and His icon. Therefore there is an artificial image of Christ, to whom the image has its relation.[10]

The iconoclast concern, then, was that the Icon could not adequately image the invisible and immaterial archetype, and even if it could, it would not deserve the same veneration as the prototype does.[11] Hence, according to the iconoclasts, the icon is at best a poor and worthless mimicry of the original, and, at worst, an idol.

The orthodox defense against the iconoclasts involved a theological demonstration of the artificial image’s intimate metaphysical relation to its archetype. This relation was made possible in the first place by the Incarnation of the Son, who ‘filled [matter] with divine energy and grace.’[12] In a sense then, there is a real presence of Divinity in the icon, by virtue of its participation in the Divine form; thus the icon is venerable.[13] However, it is not the material object of the icon that is venerated. The material itself remains plain and carnal.[14] It is the form that is depicted that deserves veneration—by ‘the identity of likeness’ to the archetype, the image and the archetype are venerated together.[15] St. Theodore explains the relation of essence and form:

It is not the essence of the image which we venerate, but the form of the prototype which is stamped upon it, since the essence of the image is not venerable. Neither is it the material which is venerated, but the prototype is venerated together with the form and not the essence of the image. But if the image is venerated, it has one veneration with the prototype, just as they have the same likeness. Therefore, when we venerate the image, we do not introduce another kind of veneration different from the veneration of the prototype.[16]

In other words, if the icon is a faithful depiction of the archetype, it is metaphysically connected to the archetype and can receive its attributes. Conversely, an image that is not created with this faithfulness to the archetype is defined as an idol.

What is important is not the visual likeness but the likeness of intention. The iconographer does not consider visual realism as her utmost goal.[17] She strives to be faithful to the image of the archetype as imprinted in her soul. St. Theodore explains this intentional faithfulness by quoting Pseudo-Basil:

In general, the artificial image, modeled after its prototype, brings the likeness of the prototype into matter and acquires a share in its form by means of the thought of the artist and the impress of his hands. This is true of the painter, the stonecarver, and the one who makes statues from gold and bronze: each takes matter, looks at the prototype, receives the imprint of that which he contemplates, and presses it like a seal onto his material.[18]

Hence, the spiritual relationship between the archetype and the iconographer is extended to the icon. It is only after the artist has ‘receive[d] the imprint of what he contemplates’ that an authentic icon can be created. Thus, not only artistic abilities and creativity, but also embodied spiritual life such as prayer and spiritual discipline, are necessary for the iconographer. It is the desire to see and know the archetype that inspires one to paint or venerate an icon.[19] This also implies that, if the iconographer does not relationally know the archetype, the icon is no longer a valid image of the prototype. The connection between the image and the archetype is severed, and the image is not a proper icon (εἰκών) but an idol (εἴδωλον).

Hence, the spiritual relationship between the archetype and the iconographer is extended to the icon. It is only after the artist has ‘receive[d] the imprint of what he contemplates’ that an authentic icon can be created. Thus, not only artistic abilities and creativity, but also embodied spiritual life such as prayer and spiritual discipline, are necessary for the iconographer. It is the desire to see and know the archetype that inspires one to paint or venerate an icon.[19] This also implies that, if the iconographer does not relationally know the archetype, the icon is no longer a valid image of the prototype. The connection between the image and the archetype is severed, and the image is not a proper icon (εἰκών) but an idol (εἴδωλον).

Now, let us imagine what an icon-painting ML algorithm would do. The first step it must take is to ‘learn’ the dataset of existing icons. This would be done by ‘training’ the neural network over a labeled dataset of various icons to classify them. We do not have to imagine this step, since there are already published papers that attempt this.[20] Here, the digitized images are ‘transformed and augmented’ to be statistically analyzed based on features such as each pixel’s color values and its relatedness to the surrounding pixels.[21] Then, according to the state-of-art research, the algorithm would use a GAN to generate an image. To put it simply, a GAN involves two neural networks: one that tries to generate artificial samples and the other that tries to discriminate between artificial and real samples. The generator network adapts to produce more ‘real’ samples based on the feedback from the discriminator network, in order to ‘trick’ the latter. The final resulting image from the algorithm would be one which had most successfully tricked the discriminator neural network, which could not distinguish the produced image from an actual icon based on its training.

Would the resulting image be an icon? It could appear indistinguishable from an icon painted by a human iconographer. However, we could understand the algorithm as an ‘idolatrous mind,’ as Dr. Jordan Wales has aptly suggested, since it has no ability to contemplate the icon’s archetype and ‘clings’ to its restricted comprehension of the archetype.[22] The initial learning phase could be compared to an idolatrous memory, and the generating phase to a form of idolatrous creativity.

The AI’s essential inability to grasp the whole of reality, material and spiritual, implies that its ‘memory’ can only be an idolatrous one. As we have established, one must not focus solely on the material appearance of the icon, but this is precisely what the algorithm cannot but do. St. Theodore writes,

The mind does not remain with the materials, because it does not trust in them: that is the error of the idolators. Through the materials, rather, the mind ascends toward the prototypes: this is the faith of the orthodox.[23]

To borrow an Augustinian concept, one must use the image in order to enjoy the form behind the icon. But the algorithm and the computer can only halt at the visible material, and a distorted form of visible material at that. In the computer, there is no prayer nor contemplation: no spiritual capacity to relate to the archetype. The algorithm can merely learn what the images of the archetype looks like, not how the archetype itself is. In a sense, it is ‘always learning and never able to arrive at a knowledge of the truth.’ (2 Tim 3:7, ESV) While in the human memory, the icons are essentially connected to the person of the archetype, in the ‘memory’ of the AI, the icons are relegated to be idols, disconnected from who they were intended to image.

Of course, this was a hypothetical question in the first place, but it does speak to a more general concern regarding AI-generated art. When one enters a query into an AI art generator, what really is the metaphysical relation between the resulting image and what the person had in mind? And is all art not some form of image of some archetype in the artist’s mind? Then, how much could AI be really used, even as a tool, to produce legitimate artwork? Perhaps answering these questions would require further philosophical and aesthetic considerations in different avenues. But, to the question of the proliferation of AI generated art, this paragraph from Augustine feels fitting as a conclusion:

Of course, this was a hypothetical question in the first place, but it does speak to a more general concern regarding AI-generated art. When one enters a query into an AI art generator, what really is the metaphysical relation between the resulting image and what the person had in mind? And is all art not some form of image of some archetype in the artist’s mind? Then, how much could AI be really used, even as a tool, to produce legitimate artwork? Perhaps answering these questions would require further philosophical and aesthetic considerations in different avenues. But, to the question of the proliferation of AI generated art, this paragraph from Augustine feels fitting as a conclusion:

To entrap the eyes men have made innumerable additions to the various arts and crafts, … pictures, images of various kinds … Outwardly they follow what they make. Inwardly they abandon God by whom they were made, destroying what they were created to be. But, my God and my glory, for this reason I say a hymn of praise to you and offer praise to him who offered sacrifice for me. For the beautiful objects designed by artists’ souls and realized by skilled hands come from that beauty which is higher than souls; after that beauty my soul sighs day and night. From this higher beauty the artists and connoisseurs of external beauty draw their criterion of judgement, but they do not draw from there a principle for the right use of beautiful things. The principle is there but they do not see it, namely that they should not go to excess, but ‘should guard their strength for you’ and not dissipate it in delights that produce mental fatigue. But, although I am the person saying this and making the distinction, I also entangle my steps in beautiful externals. However, you rescue me, Lord, you rescue me. ‘For your mercy is before my eyes’. [24]

[1] Sakib Shahriar, “GAN Computers Generate Arts? A Survey on Visual Arts, Music, and Literary Text Generation Using Generative Adversarial Network,” Displays 73 (July 1, 2022): 102237, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2022.102237. [2] Aditya Ramesh et al., “Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents” (arXiv, April 12, 2022), https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2204.06125. [3] Gabriel Nicholas, “These Stunning A.I. Tools Are About to Change the Art World,” Slate, December 11, 2017, https://slate.com/technology/2017/12/a-i-neural-photo-and-image-style-transfer-will-change-the-art-world.html. [4] Aaron Hertzmann, “Can Computers Create Art?,” Arts 7, no. 2 (June 2018): 18, https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7020018.

Although I have much objections to his view, Hertzmann contributions to this debate as a prominent computer graphics researcher is particularly interesting.

[5] Mark Coeckelbergh, “Can Machines Create Art?,” Philosophy & Technology 30, no. 3 (September 1, 2017): 285–303, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-016-0231-5. [6] For the scope of this essay, I am specifically focusing on the idolatrous relationship between the AI ‘iconographer’ and the ‘icon,’ not the human venerator and the AI-generated icon. Although there are interesting issues that particularly arise in the second relationship, once we establish that the essential idolatrous dynamic in the creation of an AI-generated icon, the second relation boils down to the question of whether we can venerate an ‘icon’ that has no proper relation to its archetype. [7] Broadly understood, this implies that what one requests an algorithm to produce may have a questionable metaphysical relationship to what it actually returns. Then, this may help answer questions such as whether one could attribute authorship of an AI-produced artwork to the user of the AI tool or whether one should employ AI to deal with ethical problems. [8] St. John of Damascus, Treatise on the Divine Images III.18, in Three Treatises on the Divine Images, trans. Andrew Louth, First edition., St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press Popular Patristics Series ; [24] (Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2003), 96.[9] St. John of Damascus, Treatise on the Divine Images III.20, trans. Louth, 98.

[10] St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Icons III.B.2, trans. Catharine P. Roth (Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1981), 100. [11] St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Icons II.12, trans. Roth, 49. [12] St. John of Damascus, Treatise on the Divine Images I.16, trans. Louth, 29. [13] St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Icons I.12, trans. Roth, 33. [14] St. John of Damacus, Treatise on the Divine Images I.36, trans. Louth, 43. [15] St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Images III.C.1, trans. Roth, 101-02. [16] St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Images III.C.2, trans. Roth, 102. [17] St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Images III.C.5, trans. Roth, 104. [18] St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Images II.11, trans. Roth, 49. [19] St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Images I.36, trans. Roth, 43. [20] Federico Milani and Piero Fraternali, “A Dataset and a Convolutional Model for Iconography Classification in Paintings,” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 14, no. 4 (July 16, 2021): 46:1-46:18, https://doi.org/10.1145/3458885; Nicolas Gonthier et al., “Weakly Supervised Object Detection in Artworks,” 2018, 0–0, https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_eccv_2018_workshops/w13/html/Gonthier_Weakly_Supervised_Object_Detection_in_Artworks_ECCVW_2018_paper.html. [21] Milani and Fraternali, “A Dataset and a Convolutional Model for Iconography Classification in Paintings,” 9. [22] Jordan J. Wales, “Metaphysics , Meaning, and Morality: A Theological Reflection on A.I.” Journal of Moral Theology, March 1, 2022. [23] St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Images I.13, trans. Roth, 34. [24] St. Augustine, Confessions X.xxxiii, trans. Henry Chadwick, Oxford World’s Classics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 210.