A moving, powerful interview with the artists behind the exciting PUSH PUSH exhibition in Dundee continues our series exploring the ‘art of poverty’. The PUSH PUSH exhibition in the Federation Gallery, Dundee was an exhibition by three artists, Flannery O’Kafka, Owen Daily and David McCulloch (Cully). It was a response to overcoming personal struggles, while the artists also wanted to acknowledge how their art sat within the context of current global adversity and more locally as the UK faces a ‘cost of living crisis’. More information about the exhibition and gallery can be found here. ITIA Editor-in-Chief Ewan Bowlby interviewed the artists to find out more about their motivations, inspiration and creative process for PUSH PUSH.

- Ewan Bowlby: There is a sense in each of your pieces of reaching toward nature in response to personal and global adversity. Why did you each choose to draw the natural world into your work, or did that emerge organically as you wrestled with struggles?

David McCulloch: It was an interesting coincidence that nature featured in our individual works. Once we recognized the connection it opened a conversation about the gallery as a space itself and of bringing nature into that space. Thinking about nature made us aware of what was happening in the world, the destruction in Ukraine and the devastating flooding in Pakistan.

We began to consider how the exhibition collectively could move beyond overcoming personal struggles to responding to a wider global adversity.

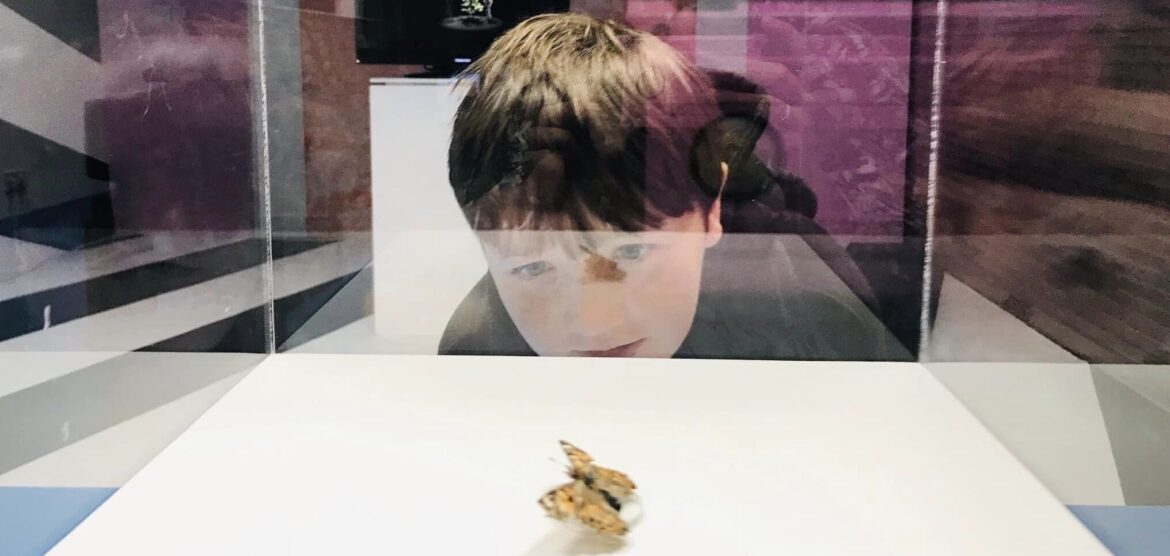

Flannery O’Kafka: When Cully approached me with the exhibition PUSH PUSH and the work he wanted to show (his film attempting to move a hay bale), it somehow made sense to memorialise Crumple (my late disabled pet butterfly) and bring him into that space. Maybe it’s the ridiculous actions we do to try to push back at the lack of agency we have…it’s hard to pinpoint how these things happen…the conversations between us and our relationship and my difficulties and responding to the gallery space…Crumple came in a butterfly kit—his siblings all flew away, but he was injured coming out of his chrysalis and ended up being a part of our disabled household that is cared for and kept going with a delicate framework of communal support and care. It’s a bit impossible to separate these things out—my art practice is intuitive, extremely personal and tied up in my domestic life. Caring for a butterfly who couldn’t fly was more the natural world drawing me into it rather than the other way around. We had a close relationship. It revolved around oranges and me misting him daily. If he had been born this year, however, he would not have survived for 80 days—I would not have been able to afford the heating needed to keep him alive.

Owen Daily: I think one of the struggles in art can be to find a language that is personal and universal. Historically, Western art had a fairly well understood iconography or visual language to draw upon, but arguably that isn’t the case now.

I find great comfort in the natural world and resonate with the Psalmist (e.g. Ps 19) who saw it as God’s handiwork. Culturally, this love of nature is held by many who wouldn’t profess any belief in line with the Psalmist but who see our need to tend, preserve and care for our world.

As I mentioned in the exhibition text, my film emerged organically in response to illness and struggle in my life. I was looking for a way to create some good out of a bad experience. Using natural elements helped that search for a personal and universal visual language that, hopefully, people could identify with.

- EB: Why did you decide to invite people to bring cans of soup? Does soup hold a particular resonance for you?

DM: The straw bale in my work was a reminder of harvest season. I remember in church when I was young that during harvest time, we were encouraged to bring food that could be donated to those who were in need. When we had the idea to use the gallery as a collection point for gathering food, we spoke to Eagles Wings charity [a Dundee charity supporting those who are homeless] to ask what a suitable food would be to collect. They suggested soup. Soup cans coincidentally brought a regimented pattern-based aesthetic to the exhibition that was pleasing. We were aware of the reference to Andy Worhol’s soup can prints and his critique (or embrace) of commerciality and excess. Considering our response to the cost-of-living crisis, this was an unintentional but striking way to contrast these values.

FO: We had the idea of making a sort of ‘harvest table’ or a ‘food library’ that would be for giving or taking, depending on need. This was partly influenced by the space being a former shopping centre, and also gave the opportunity for the viewers of the exhibition to participate in an action in the gallery space.

OD: It was a practical solution for the gallery in that it was manageable and clean. It was also a simple participatory act that might remind us of the cycle of food production/ consumption: a form of harvest Thanksgiving that, at the same time, may meet a need, in even a small way.

- EB: At Transpositions, we have found that running a series on the ‘art of poverty’ has felt daunting and dangerous at times, because we are aware that this is a subject that is so raw and immediate in many peoples’ lives now. Was your experience of making art engaging with the ‘cost of living crisis’ comparable?

DM: Our experience was very comparable. We didn’t want to make a token or patronizing gesture. I think that speaking to Eagles Wings director Mike Cordiner about our intentions and listening to his advice helped to guide our actions. This was the first time we had made an exhibition where the work wasn’t there just for disinterested engagement but would serve as a catalyst for shifting emotion into action. It has been a learning experience trying to combine art and social action while respecting what each offer to society in different ways.

FO: I mostly work with photography which has a very complicated history (and ongoing relationship) with marginalised people and suffering. I’m mostly interested in insider work. I don’t want to see the spectacle of the ‘other’ from a journalistic or art school gaze that finds the struggle ‘fascinating’, or even a middle-class Marxist gaze that fuels pity and has people reaching in their pockets.

I think the most important thing is that the rawness and immediacy has always been here for marginalised people, it’s just more visible now that more people are affected.

Having said all of that, the outrageousness of being artists and having an exhibition where we push hay bales, honour butterflies, and re-leaf trees wasn’t lost on me. We put our small actions of hope on display and perform our suffering. But I know of no other way to deal with the lack of accessible education, mental health support, trans healthcare and rising living costs that affect me and my children daily.

OD: During lockdown there was a lot of spontaneous art appearing, from ‘thank you NHS’ banners to painted pebbles. It seemed a hopeful and defiant act during a deeply troubling time. It provided a sense of relief and agency for the makers and encouragement for the receivers. Contemporary art can be seen to be detached from reality and enmeshed with capitalism. If there is empathy, then maybe we can engage in the conversation in a peer-to-peer manner as lockdown art did.

- EB: What do you each understand by ‘overcoming’ in this context, and how does overcoming manifest itself in your works?

DM: I think that Owen and Flannery’s works reveal a positive sense of overcoming, either through bringing a tree back to life or nursing a butterfly to four times beyond its life expectancy. The action in my work seems futile but perhaps repetition and not giving up is also a way to overcome.

FO: Unfortunately, I live at the sharp end of these things currently. There is no overcoming. There is only surviving: keeping your head above water or debasing yourself to get assistance in a bid to be independent. I am doing my best to keep my family and community warm, fed and alive. This is not to say I don’t have hope; as a counterpoint to ‘overcoming’ in my work, I would say that I focus on subverting. For this exhibition, I chose to honour the least of all things & the ridiculous—the tattered body of my disabled pet butterfly, Crumple. He was a beautiful boy and a Painted Lady. I love that there were people queuing up to view his body in a defunct retail space.

OD: For me, art making is both futile and fundamental. Given the scale of the issues we face, I often think ‘what’s the point?’ There is always resistance from my inner critic. On the other hand, challenging that critic by making art validates my sense of self and my experiences, and has helped me to overcome a difficult period and make sense of it. The film’s motifs remind me that things I thought impossible can be overcome.

- EB: The personal, intimate and vulnerable qualities of the artworks are deeply affecting. Did you find it difficult to create and sustain a sense of connection between such personal struggles and a situation as vast and changeable as the context of “current global adversity”?

DM: It wasn’t vital that someone knew what our particular struggle was but rather that they could resonate with the battle to overcome struggles. Human suffering and resilience are universal, so whether the struggle is personal, part of a local community or global, the connection would always be sustainable.

In Nicholas Wolterstorff’s book Art Rethought: The Social Practices of Art, he states: ‘Art cannot change the world, but it can contribute to changing the consciousness and drives of men and women who could change the world’.

If our art could resonate with various people on a private, emotional level, it might be that the sum of their individual responses could lead to helping tackle local, national or even global adversity.

FO: I suppose I would find it difficult/impossible to separate the two. So much personal and systemic suffering is the result of oppression by those who protect their power at all costs. And the other side of that is the solidarity in liberation for the most disenfranchised which results in liberation for all people, creatures and land.

I will say that I did not anticipate how vulnerable it would make me feel to bring Crumple and his story into the space. It’s about a butterfly, but it’s also about keeping my children alive in a world that isn’t always kind to fragile people.

OD: The current situation can feel grim and overwhelming, but reflecting on the natural world reminds me of the goodness and sovereignty of God and the resilience of his design.

- EB: What sort of responses has the exhibition drawn from visitors? Can you give some examples of specific interactions?

DM: A lot of people took photos of themselves standing in front of the straw bale or beside Crumple the butterfly. There must have been something in those objects that people could resonate with or want to keep as a memory.

The most encouraging responses for me were when people had visited the exhibition without knowing about the soup collection and would then return later with soup, once they knew what the exhibition was about. This action of taking time to go and buy soup and return was a good indication that people had been moved.

FO: I was present for the opening day and had some lovely conversations. The reaction by children, especially, was probably the best thing for me. They all seemed to love Crumple and really connect to the story of his life and his tiny body. Also, the way children approached the whole gallery space was often with a curiosity and openness. I heard one passing child say ‘can I go in there?’

OD: I was pleased when young teens stopped and stared and asked the curator how it was made. I was surprised they appreciated the quietness of it and returned with their friends to engage with the whole show.

Gallery owner Kathryn Rattray reflects on the PUSH PUSH exhibition and the public response:

It was a feast for the imagination filled with humour, soul and artistic excellence. Aesthetically capturing, our audience was drawn in by the warm oranges and the moving images on screen. As Crumple the Butterfly lay peacefully in state, we remembered what it means to care.The gallery filled every day with interested and curious people. I knew we were on to a good thing when a group of young people stopped and said, ‘This is like Stranger Things’. We collected around 100 cans of soup for Eagles Wings charity, conversations around the cost-of-living crisis and the strain of rising costs and sanctions. War, greed and corrupt political decisions were at the heart of it.

I will miss PUSH PUSH. I will miss explaining to our audience that this exhibition is about love, caring and kindness. I will miss telling others what Martha and Mary, the sisters of Lazarus, said to Jesus: ‘Someone You Love is Sick’. A powerful reminder to take care of each other more.

Thank you to everyone who visited us.

Thank you to Cully, Flannery and Owen for creating something so extraordinarily special.

Kathryn Rattray – Federation Gallery

Owen Daily lives and works in Dundee and is co-founder of Nomas* Projects and Sharing Not Hoarding. His personal practice gravitates around meaning and absurdity and spans printmaking, photography, video and sculpture. He is a visiting tutor in Adobe Creative Suite and LaTeX at the University of St Andrews’ Centre for Educational Enhancement and Development (CEED).

Flannery O’kafka (she/they) is an artist living and working in Glasgow. Their practice is mostly photographic, but she also works with text & installation, writes filthy poetry, and broadcasts a stupid amount of Instagram stories most days. All work is an emotional document, a cumulative clumsy stab at a self-portrait, a mourning diary—a public autobiographical/fictional exhibition of suffering & stigmata, and an examination of the picturing of disability.

David McCulloch (Cully) is co-founder of Morphē Arts. He is based in Dundee but also works with artists in Glasgow and Edinburgh. His multi-disciplinary art practice includes print and sculpture and encompasses the programming of two alternative gallery spaces – Nomas* Projects and Sharing Not Hoarding – with a focus on the role of the artist in society.