Jeremy Begbie. A Peculiar Orthodoxy: Reflections on Theology and the Arts. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2018. 214 pp. £24.99 / $32.

Editor’s note: Jeremy Begbie, co-founder of ITIA and a pioneer in the academic scholarship and aesthetic practice related to the disciplines of theology and the arts, has published two books in 2018. We are pleased to offer reviews of both in the next two Friday publications of Transpositions.

Jeremy Begbie’s most recent contribution to theological aesthetics, A Peculiar Orthodoxy: Reflections on Theology and the Arts, is a collection of previously published material with a new Introduction and a brief abstract prefacing each chapter. Each chapter is a slice from the Begbiedian feast, pursuing a basic thesis that the doctrines of the Trinity and the Incarnation provide Christianity with a unique theological resource for aesthetic practice and theory – namely, that the dynamics of intratrinitarian love and processions, and the revelation of divine being afforded by the Incarnation illuminate and, in some cases, overthrow commonly held notions of beauty and the artistic enterprise. It is a study of the aesthetic implications of Christianity’s ‘peculiar orthodoxy’.

Not surprisingly, given that Begbie is a trained and talented musician, most of the artistic examples are from the realm of music, particularly classical music, and for this former music major the book is an enjoyable re-reading of Begbie’s familiar reflections on how music, as particularly exemplified in the work of J S Bach, reflects and illuminates aspects of created existence and its eschatological trajectory through elements of rhythm, melody, harmony, and the ways musicians harness and exploit the possibilities of these elements. His summary and evaluation of recent research on the psychology and neuroscience of music and the emotions is particularly fascinating.

Not surprisingly, given that Begbie is a trained and talented musician, most of the artistic examples are from the realm of music, particularly classical music, and for this former music major the book is an enjoyable re-reading of Begbie’s familiar reflections on how music, as particularly exemplified in the work of J S Bach, reflects and illuminates aspects of created existence and its eschatological trajectory through elements of rhythm, melody, harmony, and the ways musicians harness and exploit the possibilities of these elements. His summary and evaluation of recent research on the psychology and neuroscience of music and the emotions is particularly fascinating.

So much could be said about this book, but I wish to focus my reflections on ways in which it is related to the work of the Institute for Theology, Imagination and the Arts (ITIA). Begbie himself is a co-founder of the Institute, and a central chapter of his book is taken up with his response to the work of David Brown, emeritus professor at the Institute (full disclosure – I did my PhD under Brown’s supervision). Their ongoing dialogue highlights themes of theological method, criteria of evaluation and identification, and differing points of emphases that have important implications for the kind of research and scholarship that take place at the Institute.

First is the enduring matter of theological criteria. For Begbie and others of a Calvin/Barth/Torrance orientation, Brown’s reticence in his publications to articulate a full-blown guideline to the proper identification of God’s presence in art and culture represents a serious weakness in Brown’s theological aesthetics. What is interesting to note in Begbie’s new volume is his own reticence towards criteria in relation to beauty. For a number of stated reasons, Begbie feels that the familiar canons of beauty (proportion, radiance, integrity) can be too quickly stifling, too easily invoked, and therefore too easily domesticated or dismissed when considering a work of art or its potential impact. Irony aside, the parallels between these two scholars over the imposition of criteria for the discovery of divine presence or beauty is a matter with which everyone involved in theological aesthetics needs to wrestle.

A second area of contrast involves an understanding of the means by which God makes himself present or accessible in creation and art. Throughout this volume, Begbie repeatedly highlights the role of the Holy Spirit. It is by the Holy Spirit that God makes his appeal to humanity and by which humanity has access to accurate knowledge of God. This in turn relates to Begbie’s concern that God is singularly revealed in the Incarnation of Christ. Brown opts for a different approach: ‘Although nowadays it is the Holy Spirit that is usually credited with working outside the Church, in the past it was once Christ as Logos’. [1] Brown opts for this classical or more Catholic orientation toward the logoi of creative acts reflecting the originating Logos of all creation, of a universe hard-wired, as it were, with knowledge of God available to those both inside and outside the sphere of special revelation.

A third point of observation involves Begbie’s persistent conflation of beauty and goodness. Throughout the book Begbie issues assertions such as this: ‘As far as divine beauty is concerned, if the “measure” of beauty is self-dispossessing love for the sake of the other, we will need to come to terms with excessor uncontainability, for the intratrinitarian life is one of ceaseless overflow of self-giving’. [p. 11] Substitute the word ‘goodness’ for ‘beauty’, and that sentence would, to me, make much more sense. There is throughout the book these kinds of moral evaluations of the acts of God which are then commended as criteria of aesthetic beauty, expressed without any reference to artistic examples. As a theological aesthetic, that sentence, and the many like it, should be immediately qualified with something like ‘as seen for example in the work of…’ or ‘in X’s painting of…’

Begbie’s book is full of valid and suggestive principles that are too often left in the abstract. This is a major deficit for a work of aesthetics.

One of the contributions of theological aesthetics to theology is the insistent practice of making principles palpable, of rendering abstractions concrete, of incarnating ideas with the flesh of creativity.

If some principle of beauty is invoked, we should know what it looks like, tastes like, smells like, feels like, or sounds like.

In this regard, Begbie’s project could be advanced through a triangulation of his own Protestant, Brown’s quasi-Catholic, and the Eastern Orthodox traditions. If anyone has a ‘peculiar orthodoxy’ in Begbie’s sense of the term, it surely is the Orthodox, with their insistence, for example, that icons are works of theology and not mere illustrations of theology. They speak unhesitatingly of the visible beauty of the saints in their participation in divination as presented in iconography. Their contribution is absent in this volume.

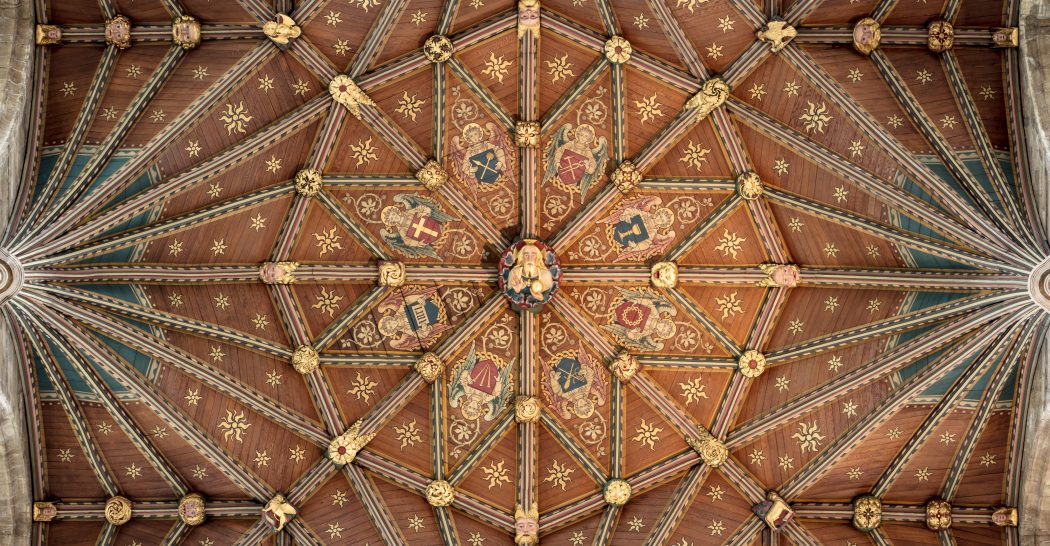

Finally, his brief protestations against this impression notwithstanding, there is an aniconism about Begbie’s project, a hesitancy when it comes to visible representations or presentations of the Divine, an anxiety about representational art. He likes the ear; he distrusts the eye. That his examples come primarily from the realm of music is certainly understandable given his own background. But how does one write a whole chapter on poetry with next to nothing on poetic imagery? The almost exclusive recourse to the (presently) invisible realm of the Intratrinitarian Life, and the insistence on a strictly pneumatic basis by which God makes his appeal, seems to function to relieve Begbie of metaphysical heavy-lifting, a too easy dismissal of the natural theology tradition and, as noted above, a preference for the verbal and aniconic. At this point some readers will want to refer me to the final chapter, where Begbie anticipates and responds to some of the criticisms I’ve raised. He does appear to have heard much of this before, which only begs the question of why he chooses to continue to reinforce the impressions his writings produce.

Jeremy Begbie has made an invaluable contribution to the discipline of theological aesthetics over many years. I am among the beneficiaries of his work. But there is a repetitiveness in his recent work that could stand for some fresh thinking and further conversation.

[1] David Brown, God and Mystery in Words (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 3.