In one of his many essays on Milton, Northrop Frye defines the epic poem as a ‘special kind’ of narrative poem that does more than simply recount a heroic narrative; the epic, he argues, additionally offers an ‘encyclopedic quality, . . . distilling the essence of all the religious, philosophical, political, even scientific learning of its time’. If done well, it will be the ‘definitive poem for its age’. [1] For those interested in the intersection of poetry and theology, not to mention all general lovers of poetry, one of the major publishing events of recent years must surely be the 2018 publication of Micheal O’Siadhail’s The Five Quintets (Baylor University Press), a work that aspires to fulfill the considerable demands of Frye’s attributes of an epic by offering a sweeping engagement with Western culture’s last five hundred years while it also looks ahead to a heavenly fulfillment that transcends the possibility of any human culture.

O’Siadhail has been a friend of the Institute for Theology, Imagination and the Arts in St Andrews since he was invited to visit several years ago by co-founder Trevor Hart. On the occasion of his recent visit to St Andrews to give a reading, I enjoyed the opportunity to talk with O’Siadhail about his new poems and about poetry in general. [2] In both my conversation with him and my reading of his new book, three aspects of The Five Quintets stand out: intellectual breadth, artistic responsibility, and eschatological generosity. In an era of public discourse that often swings wildly between harsh rhetorical attacks against opponents and an unwillingness to venture any moral discernment, O’Siadhail’s balanced and charitable poetic effort to come to terms with the whole course of Western modernity demonstrates how one may evaluate and critique without at the same time condemning those of a different creed or philosophy. For O’Siadhail, discernment does not inevitably lead to separation, nor must a desire for community lead to relativism.

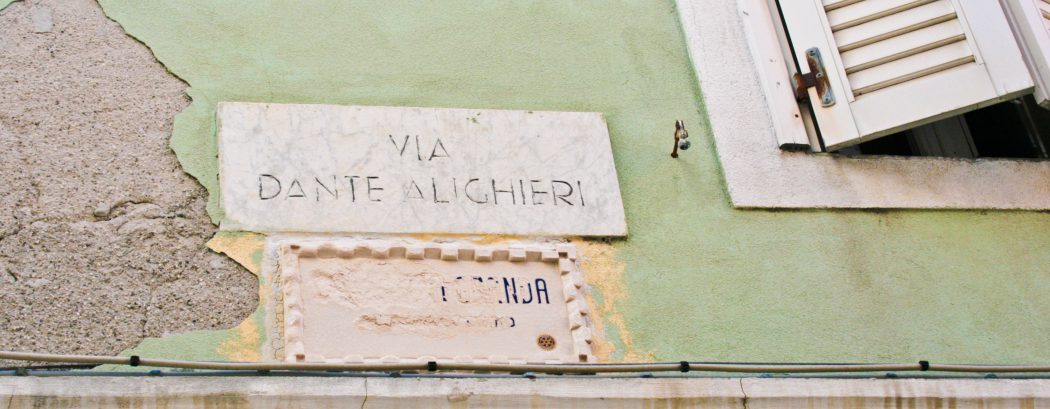

2018 has been a major year for O’Siadhail: in addition to the publication of The Five Quintets, Baylor University Press has also recently republished his 800-page Collected Poems. Over the last four decades, O’Siadhail’s collections have ranged across many topics, from the Holocaust (The Gossamer Wall) to his first wife’s prolonged struggle with Parkinson’s disease (One Crimson Thread). Despite the overall breadth of his previous work, however, none of it taken singly compares in scope to the ambitious project that is The Five Quintets. O’Siadhail himself, however, hesitates to call his new poem cycle an epic. ‘Epic is better used by somebody else than by yourself’, he says, ‘but it is certainly my magnum opus’. Still, the Irish poet cites Dante as the ‘model’ for what he tries to do in the quintets. ‘It seemed to me that Dante had come at the end of the Middle Ages, at the beginning of the transition into what we call modernity. . . . I wanted to look at modernity, to see how it had come about, how we had transitioned into it’. In O’Siadhail’s view, our culture has witnessed or is still witnessing its own shift to something different, whether one chooses to label that change ‘late modernity, postmodernity, chastened modernity, even liquid modernity. I felt all the old certainties in some way had broken or fractured.’ On a worldly level, then, both O’Siadhail’s and Dante’s poems wrestle with cultural paradigm shifts even as they also reach beyond those human, worldly realities to spiritual ones.

2018 has been a major year for O’Siadhail: in addition to the publication of The Five Quintets, Baylor University Press has also recently republished his 800-page Collected Poems. Over the last four decades, O’Siadhail’s collections have ranged across many topics, from the Holocaust (The Gossamer Wall) to his first wife’s prolonged struggle with Parkinson’s disease (One Crimson Thread). Despite the overall breadth of his previous work, however, none of it taken singly compares in scope to the ambitious project that is The Five Quintets. O’Siadhail himself, however, hesitates to call his new poem cycle an epic. ‘Epic is better used by somebody else than by yourself’, he says, ‘but it is certainly my magnum opus’. Still, the Irish poet cites Dante as the ‘model’ for what he tries to do in the quintets. ‘It seemed to me that Dante had come at the end of the Middle Ages, at the beginning of the transition into what we call modernity. . . . I wanted to look at modernity, to see how it had come about, how we had transitioned into it’. In O’Siadhail’s view, our culture has witnessed or is still witnessing its own shift to something different, whether one chooses to label that change ‘late modernity, postmodernity, chastened modernity, even liquid modernity. I felt all the old certainties in some way had broken or fractured.’ On a worldly level, then, both O’Siadhail’s and Dante’s poems wrestle with cultural paradigm shifts even as they also reach beyond those human, worldly realities to spiritual ones.

Dante frames his Commedia very clearly as a journey from hell to paradise, and on his way the pilgrim constantly speaks with the souls he encounters. Often more subtly but no less definitely, The Five Quintets follows a similar path and uses a similar technique: within the narrative structure of imagined conversations with real, historical people, many long dead but a few still living, O’Siadhail offers readers a poem about journeying across the breadth of a culture’s life and striving for paradise. Some of his figures are among the most famous in our history (Shakespeare, Mozart, or Darwin) while others will be obscure or unknown to readers outside of specific disciplines (Robert Owen or Clerk Maxwell), but O’Siadhail emphasizes that all of the people he has selected are ‘representative, not exclusive. They’re symbolic of a certain era within modernity’. Or as he writes in the first canto of the fifth quintet, they are ‘a chosen few whose work and one-time fame / have tied our drifting history’s tangled nets’ (291).

Taken ‘horizontally’, the five quintets range across the cultural spheres of the arts (‘Making’), economics (‘Dealing’), politics (‘Steering’), science (‘Finding’), and theology and philosophy (‘Meaning’). ‘I loved the echoes . . . of hell, purgatory, and heaven’, says O’Siadhail, ‘but then I needed a five-part structure. I wanted to show the transitional figures transitioning from the Middle Ages into modernity’. When he looked across these various cultural segments, O’Siadhail perceived a similar shape in their historical paths, so each quintet therefore employs an identical five-part structure by which O’Siadhail ‘tried . . . to unify it vertically’. Within that vertical dimension, each quintet follows a general path of descent and reascent through its five ‘cantos’. The first canto of each quintet introduces figures like Cervantes or Copernicus who helped prompt various cultural transitions from the medieval to the early modern. Cervantes, for instance, while he mocks ‘all hankering for a courtly love, / The lost and gone of tournament and lance’, also hatches ‘Erasmus dreams of tolerance / Between the Middle Ages and your tour / Through plots and greeds of bungling humankind’ (1). [3] In the second cantos, O’Siadhail offers portraits of figures who he says ‘in certain cases go for freedom and in others for fixity’. In the realm of music, for example, O’Siadhail’s Beethoven asserts, ‘My notes transverse a still unplotted chart; / Beyond polyphony or court delights / I sound the depths of unbeholden art’ (15). The central third canto of each quintet, however, reaches ‘the nadir, which echoes Dante’s hell’. Here we encounter figures like Nietzsche or Sartre who variously represent isolation from others through excessive individualistic freedom or extreme ideological control. Moving into the fourth parts, readers reach those ‘who echo purgatory, who have a fresh vision: they don’t quite get there, but they try’. In other words, they realize the need for a fresh approach. In science, for instance, this level is where O’Siadhail places Einstein, whose work with relativity began to ‘overthrow / the frames of time and space we think we know’ (263). Each final canto, according to the poet, ‘reverberates with Dante’s heaven with people from all across the four hundred years’, figures as diverse as Dietrich Bonhoeffer, John M. Keynes, and Willa Cather, who all somehow contributed to an ongoing birth of the future just as Dante himself saw ‘a flowering unseen’ of a possible European rebirth (38).

Working within this parallel structure, however, each quintet utilizes a different verse form, some traditional and some created by O’Siadhail. For instance, ‘Making’ employs a form which the poet calls ‘saikus’, which he says he loves to use ‘because it uses the most traditional form of the East [the haiku] and the most traditional form of the West [the sonnet], which are interspersed’. ‘Finding’, in contrast, is written in iambic pentameter and, in another nod to Dante, ‘Meaning’ employs terza rima.

One can understand the value or even necessity of these structuring mechanisms given the vast intellectual scope O’Siadhail explores in The Five Quintets. To an extent not even attempted by many thinkers, let alone by many poets, he truly has tried to cover the whole range of culture, including elements that rarely enter into literary writing. As he says of his economic quintet, ‘Dealing’, ‘I don’t know of anybody else who’s written about economics in poetry, so that may be a first’. Yet economic movements stemming from thinkers like Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and Milton Friedman have undeniably and profoundly shaped important parts of the modern identity, so any poetic attempt to fully grapple with that history must find space for what could be viewed as mundane or unartistic. It is a sign of the quality of O’Siadhail’s scholarship and artistry that he succeeds in conveying both authentic knowledge of each discipline (and its practitioners) and in making all of his topics artistically interesting.

One can understand the value or even necessity of these structuring mechanisms given the vast intellectual scope O’Siadhail explores in The Five Quintets. To an extent not even attempted by many thinkers, let alone by many poets, he truly has tried to cover the whole range of culture, including elements that rarely enter into literary writing. As he says of his economic quintet, ‘Dealing’, ‘I don’t know of anybody else who’s written about economics in poetry, so that may be a first’. Yet economic movements stemming from thinkers like Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and Milton Friedman have undeniably and profoundly shaped important parts of the modern identity, so any poetic attempt to fully grapple with that history must find space for what could be viewed as mundane or unartistic. It is a sign of the quality of O’Siadhail’s scholarship and artistry that he succeeds in conveying both authentic knowledge of each discipline (and its practitioners) and in making all of his topics artistically interesting.

Though O’Siadhail cites Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age as an influence on his thought, the poet also felt the need to remind himself that history is made by real people, ‘by flesh and blood and all the prejudices that come with them’, and not simply by the force of abstract ideas. The Five Quintets is profoundly a book about people, about the choices they have made and the things they have done, and the poetry impresses through its ability to balance an attitude of charitable generosity towards those people with its author’s sense of vocational responsibility.

O’Siadhail is quick to acknowledge the uncommon opportunity he has enjoyed as a professional poet: ‘I’ve always taken seriously the huge privilege that for the last thirty-one years I have been able to work as a full-time poet. That’s not a privilege many people have’. For O’Siadhail, that awareness of his vocational privilege leads to a sense of poetic responsibility which affects the kind of verse he writes. For much of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, many poets have seemingly felt that a direct relationship exists between obscurity and profundity: the more obscure, the more profound. Difficult, challenging writing has a legitimate place, and demanding poets like T. S. Eliot or Geoffrey Hill were very intentional about the way they crafted their verse. But it’s clear from The Five Quintets that O’Siadhail does not want to be needlessly obscure, and his poetry serves as a wonderful reminder that depth doesn’t need to equate to obscurity, nor does clarity and approachability need to be a sign of a simplistic approach. In that sense he reminds me of the mature W. H. Auden, who increasingly felt a sense of public vocational responsibility as his career progressed. For his part, Auden eventually recognized that he needed to write differently from how he had as a young man; writing obscure poems only understandable to a small coterie of readers might be fashionable, but it was also irresponsible for one who regarded his poetic calling as a gift.

Speaking of his own approach, O’Siadhail says very clearly that he desires ‘to talk to people who want to read poetry. I don’t want to be inaccessible, I want to be accessible’. So, while an element of mystery in the poetry will remain, just as some mystery remains in all areas of life, ‘I would never want to be obscure’ to the point that a ‘person who desires to read poetry’ couldn’t understand the poems. He reflects, ‘I like clarity. … I like clarity of thought. I like to be understood. … I don’t ever want to make it difficult, I want to make it moving. I want to move people’s hearts and minds’.

O’Siadhail’s description of his approach coincides with my own experience of reading The Five Quintets. In one sense, these are demanding poems if for no other reason than the aforementioned intellectual breadth: very few readers will be acquainted with all of the figures that the poet engages across his five disciplines. The reader who knows of the mysterious Shushani’s influence on Emmanuel Levinas, for instance, might know nothing about the British entrepreneur Richard Arkwright (322-324 and 96-99, respectively). Even so, O’Siadhail rightly hopes that the majority of the figures will be ‘largely self-explanatory’ even without prior knowledge of their lives and work. I was often intrigued enough by references to an unknown person that I wanted to at least quickly look at his or her bio, but I never felt that I had to do so to make sense of the poetry in front of me. The poems themselves do tell the stories of these people, at least in terms of their significance for the poet, and O’Siadhail ably and concisely brings out that significance for the story he tells.

As O’Siadhail recognizes, however, we can never fully know another person, and inevitably any portrait of a person will only actually be a partial, selective sketch. In The Five Quintets, which consists almost entirely of such sketched portraits, the Irish poet has attempted to hold a delicate balance between charity and critique as he treats his subjects’ lives. He doesn’t forget, first, that he is engaging with people, not ideas. In ‘Dealing’, for example, where it might be easy to treat economic theories merely like formulae that produce spreadsheets, O’Siadhail consistently keeps our attention on the humanity of his subjects by offering physical details from their portraits or pictures. Thus we read about John Stuart Mill: ‘A lanky frame, / And bald sculpted head; / Fair tufts, sideburns; / A twitching eye’ (89). The poet also often reminds us of the influence of someone’s parents and upbringing on who he or she eventually becomes, though he doesn’t allow such environmental, hereditary factors to eclipse a person’s freedom. When O’Siadhail envisions Martin Luther stepping out of his famous portrait by Lucas Cranach the Elder, the reformer tells us that ‘Hans Luther didn’t spare the rod— / a trading Europe needs its discipline’ (289). But while Luther admits that ‘Perhaps my father’s strictures tinge my God’, he also assures us, ‘Whatever else my heart is genuine’.

O’Siadhail also shows generosity towards his conversation partners in how and when he lets them speak. He says he committed to ‘giving them the last word in the conversation always’. That is, though the poetic narrator comments on, interrogates, and critiques figures, the character is always allowed to give a final response. Furthermore, O’Siadhail notes that he uses ‘a lot of their own words’ in the contexts of his poems, and he approached the task of these literary portraits by ‘seep[ing] myself in their lives, reading several biographies, staring at their portrait, thinking about them, like a dramatist in a way trying to give voice to them’. He allies these literary techniques with an effort at compassion for even the most conventionally infamous figures he engages. Regarding someone like Stalin, for example, he remembers the Russian’s final isolation: ‘I see the loneliness of his end, the isolated dictator who had done such awful things, and yet never completely beyond compassion’. The words that O’Siadhail gives to Descartes—‘Before you judge me, this one caveat: / remember well the times I’m living in’—could well apply to the author’s attitude to all of his subjects (295).

Still, O’Siadhail’s commitment to sympathy, charity, and generosity doesn’t mean that he blithely ignores what he perceives as failures, mistakes, and sins. We can try to allow caveats for circumstances, but he says ultimately ‘there has to be discernment, a moral judgement. I hope not a heavy-handed one, but there has to be one’. It seems that for this poet the salutary challenge of the postmodern era lies in developing the humility to recognize that ‘no one has monopolies on truth’ while at the same time not giving up on the reality of truth and meaning (231). ‘To fall into relativism’, he says, ‘is to fall into one of the biggest traps of the downside of postmodernity, where nothing really matters’. For O’Siadhail, we most definitely live in a world of truth and meaning, but holding on to that fact requires living in hope.

When we arrive at the poem’s eschatological vision in the final quintet’s final canto (Burning Bush), the shape of the author’s hope becomes clear. If we distill the essence of the poem’s depiction of the infernal compared to the heavenly, we might suggest the contrast between a spiritual isolation and an effort at charitable community. It is when we read of Sartre that we reach the hellish depths, ‘the frozen circle of the pit’ (314). His final words: ‘Is hell still other people in our way? / I freeze again surrounded by this ice….’ (315). On the other hand, O’Siadhail’s saints reach beyond themselves in love. As his Kierkegaard says immediately after we ascend from Sartre’s isolation, ‘Hell’s only exit passion’s mindful leap’ (318). If this attitude is true of Kierkegaard’s ‘leap of faith’ toward God it is also true of the movement of love towards other people.

In his own poetic practice of such charity, O’Siadhail employs the primary images of the feast and the dance to depict the eschatological generosity or ‘abundance’ he imagines in his heavenly visions. In his conviction that no single tradition has a monopoly on truth, he places five individuals from several religious traditions together in his visionary experience of heaven: Jean Vanier, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Hannah Arendt, Said Nursî, and John XXIII. O’Siadhail’s first wife Bríd Ní Cherabhaill, Mohammed’s wife A’isha, the Shulamite of the Song of Songs, Dante’s Beatrice, and the Virgin Mary, meanwhile, all serve as the poet’s heavenly hostesses in the final poem’s final pages. The five saints welcome the narrator to a lush, sensuous feast, an ‘abundance so beyond our need or lack’, where they enjoy ‘Gruyère, Roquefort, Boursin and Camembert; / … the endless more and more of each cuisine’ (328).

The heavenly feast evokes O’Siadhail’s ideal of charitable communion between people, but the vision of a cosmic dance accompanied by jazz more fully evokes the poet’s understanding of universal creation’s fulfillment at levels including but also transcending the human. For years, O’Siadhail has invoked ‘Madam Jazz’ as a muse, and he calls on her again at the beginning of this book to ‘Riff in me so I can conjure how / You breathe in us more than we dare allow’ (xxiii). When, in his final heavenly visions, the poet tells us that ‘a dazzling light / begins to draw me to itself and woo / me in the way a lover can invite’, we find that he now is indeed moving into ‘a skylit dance, / a dizzy whirl, a giddy dervish high’ that does not reach a peak (354-55). Instead, he now takes part in a dance that ‘peaks again and so beyond beyond, / surprising me with infinite excess’ (355).

Speaking of his choice of jazz, O’Siadhail says, ‘I love the image of jazz: [it is] the ordinary played with the most extraordinary riffs’. Importantly, jazz offers freedom to the individual to improvise, but even the wildest improvisation takes place in an ‘ensemble of people playing to one another, and trusting the riffs with one another’. Ultimately, they produce a ‘community of innovation, a community of improvisation’.

In some cases, the assertion that creation is a dance can fall prey to a mawkish sentimentality that feels like it looks past much of the lived reality of the world. In The Five Quintets, however, two important factors protect the author’s jazzy dance from such sentimentality and charge it instead with an authentic excitement. First, as the scientific quintet ‘Finding’ powerfully articulates in its account of the history of modern subatomic science, the idea of dancing may not be a mere poetic image but a physical reality of all created matter: the earlier mechanistic view of physical reality has had to open out to something much more complex but also much more alive. As the poet thrillingly recounts the scientific search for more and more subatomic particles, he asks to ‘let the dancers in the dance unfold / in litanies of subtype mesons named / “pions,” kaons,” “etas,” “Ks” and “Ds” and “Bs”’ (276).

O’Siadhail’s dance of creation also succeeds because it acknowledges the reality of suffering and still continues its movements. As his Bonhoeffer reminds him, ‘before the resurrection, first the cross’ (350). It’s for this reason, perhaps, that O’Siadhail stresses that his poem is a poem of hope rather than mere optimism. The poem’s final canto, in fact, has all five of the saints follow the lead of Mary, the one for whom Simeon foretold a pierced soul, and speak of how earthly suffering relates to heavenly joy through a deepening or hollowing of the earthly vessel. As the poet reminded me, his composition of The Five Quintets over the course of the last decade was interrupted by his writing of One Crimson Thread, which grew out of his response to the most painful events of his own life. His insistence on hope, then, and the accompanying insistence on the reality of meaning, follow his own reality of suffering.

Since Homer, the epic has always been seen as the most ambitious poetic enterprise. Besides the intellectual demands of summing up a culture and its learning that Northrop Frye required, a poet needs also to have a loving desire to affirm something about that culture. O’Siadhail’s desire to be part of and influence the public community of readers aligns naturally with the emphasis in his paradisal visions on the community of love, and the words that his Hannah Arendt speaks to him in heaven perfectly capture the spirit of this poet and his postmodern epic:

‘A poet’s work must be the interface

embracing all the wonders we’ve amassed

with gratitude but also, in the light

of what we’ve lost or thought we had surpassed,

motifs of wisdom you with second sight

will slowly rebegin to interweave.

You won’t look back to try to underwrite

all loss or hanker for some make-believe,

but in the glare of the here and now to find

a vision for our world you must conceive;

as Dante once prepared the modern mind

you too must show a depth and breadth of view

that lets the future in our now unwind’. (332)

[1] Northrop Frye, ‘The Story of All Things’, in Northrop Frye on Milton and Blake, ed. Angela Esterhammer (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), 37.

[2] Morley interviewed O’Siadhail in St Andrews on 10 October, 2018.

[3] All subsequent poetic quotations and page references come from Micheal O’Siadhail, The Five Quintets (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2018).