A little girl wants lighter skin. She stares at the back of her hand and says, “I just don’t like the way brown looks, because the way brown looks looks really nasty for some reason.”[1]

A little girl wants lighter skin. She stares at the back of her hand and says, “I just don’t like the way brown looks, because the way brown looks looks really nasty for some reason.”[1]

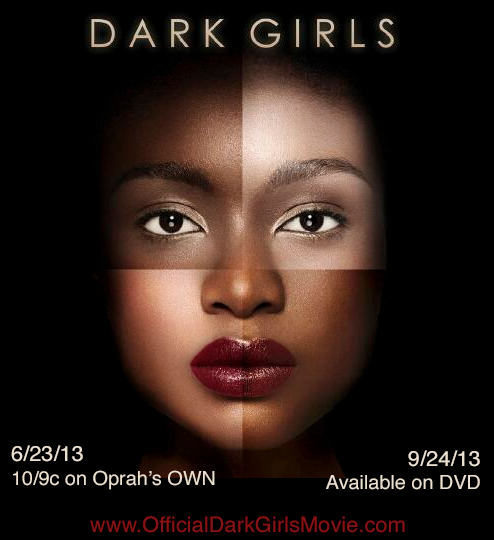

She’s not alone. In the documentary “Dark Girls,”[2] women of color testify to their experience of “colorism,” a worldwide species of racism that ranks people based on relative skin tone. One woman recounts how she would scrub her skin raw, to wash it “clean.” Another hints at the practice of using bleach to lighten skin.

The problem isn’t just prejudice. The problem is that our culture feeds us false images of human “beauty” and “goodness” to the point we internalize them, even if it means hating our own flesh.

And this means it’s a problem of idolatry. In his article “The Desire of the Church,” theologian Willie Jennings suggests that “[i]dols come into existence in the space created by our turning away from one another as men and women as well as our turning away from God. Idols live between us, facilitating distorted desire and distorting relationship.”[3] Rather than desiring others for the sake of communion, we desire for our own ends. To gain power or pleasure. To consume. To be “beautiful” no matter the cost to ourselves or those we label “ugly.”

These powerful idols of idealized humanity have racial and gendered overtones. The idols may take diverse forms, but as documentaries and studies like those referenced above imply, they visually exalt white, Western, heterosexual manhood and summon women everywhere to approximate specific, physical forms of beauty just to feel worthy, honored, and desired by those with power. These images of “goodness” and “beauty” overwhelm all of us, captivate and claim us. By giving us false visions of what to strive for, they damage not only our relationships with others, but with God and ourselves.

How can we, as Christians, escape the lure of such idols and replace them with something more wholesome? Christians might rightly suspect that the answer has something to do with Jesus. Willie Jennings talks about the problem in terms of a contest between idols, on the one hand, and Jesus as our “holy icon,” on the other. Idols offer a distorted lens for seeing others and ourselves, whereas Jesus fights to replace these with himself, so that in him we can have healthy, life-giving relationships with God, others, and ourselves.[4] If we begin to see Jesus as the one in whom God wants to unite absolutely everyone, and as the one who shows us what perfect humanity should be, then we’ll never see “dark flesh” the same way ever again.

How do we allow Christ to replace the idols that make us see dark flesh as nasty? As James K. A. Smith might put it, our perception needs to be sanctified,[5] for only then can we start to see the world from God’s point of view. Both Smith and Jennings think the church is called to help us in this task, but Jennings is “convinced that the church in this day is not prepared to challenge idol production,”[6] because Christians are too caught up in the idols that we imbibe from television and film and imitate with our clothes, cosmetics, and gadgets.

How do we move forward, then? Jennings suggests that Christ becomes our holy icon in contrast to our culture’s idols when we contemplate his life, and actual visual portrayals of Christ’s life can aid this process.[7] He also recommends that we embrace mutual subordination, which means refusing to self-define at the expense of others and instead realizing that we need each other to be what we’re meant to be: in community together with God.[8] If Christ is the one in whom we are restored to healthy relationships and sanctified perception, then when we see dark or otherwise “nasty” flesh, we recognize it as Christ’s flesh, our flesh, and beautiful precisely because it’s desired by God.

This description of “idols” and our “holy icon” is more provocative than exhaustive. What unholy images do we face when it comes to idealized humanity? How can Christ be our holy icon? How can the church participate in sanctifying our perception of ourselves and others?

Image Credit, Dark Girls graphic: https://www.facebook.com/DarkGirlsMovie

Used under the Fair Use Policy: (1) Direct comment on the product for (2) non-commercial and (3) educational purposes, which (4) doesn’t diminish the owner’s ability to gain from the image, and might even contribute to it.

[1] http://www.cnn.com/2010/US/05/13/doll.study/. Quote from the video.

[2] http://officialdarkgirlsmovie.com/. For another study, see Good Morning America’s replication of a famous baby doll experiment: http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/story?id=7213714 (and for a video on this, see http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/video?id=7216171).

[3] Willie James Jennings, “The Desire of the Church,” in The Community of the Word (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2005), 246.

[4] Jennings, 247.

[5] James K. A. Smith, Imagining the Kingdom: How Worship Works (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2013), 166.

[6] Jennings, 249.

[7] Jennings, 249. Emphasis omitted.

[8] Jennings, 250.

Great article! Thank you!

Thanks, Shane!