Richard Viladesau. The Pathos of the Cross: The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts—The Baroque Era. Oxford, UK—New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014. xvi + 344 pgs. Hardback. £35.99. ISBN: 9780199352685.

Richard Viladesau’s compellingly written The Pathos of the Cross: The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts—The Baroque Era is the latest astute monograph—after The Beauty of the Cross (2005) and The Triumph of the Cross (2008)—considering the interplay between theological notions of the cross and contemporaneous artistic expression. Viladesau’s exposition in this work successfully aims to demonstrate that “a dramatic conception of the events of the Passion, aimed at reaching the affects of the viewer and listener to produce a living relation with the God of redemption,” (x) constitutes a central feature of Baroque spirituality.

Ensuing the schismatic ecclesiastical turbulence in the sixteenth century, the Protestant and Catholic theology of the cross—and thus its respective art—developed along differing trajectories. For this reason, the author understandably decides to approach both the Protestant and Catholic traditions in two of the three separate main parts of the book, the third being concerned with the doctrine of redemption in the Enlightenment era. In each of the first two main parts, Viladesau successively touches on theological/theoretical notions of the crucifixion, the cross in visual art, and lastly its representation and place in religious music.

Ensuing the schismatic ecclesiastical turbulence in the sixteenth century, the Protestant and Catholic theology of the cross—and thus its respective art—developed along differing trajectories. For this reason, the author understandably decides to approach both the Protestant and Catholic traditions in two of the three separate main parts of the book, the third being concerned with the doctrine of redemption in the Enlightenment era. In each of the first two main parts, Viladesau successively touches on theological/theoretical notions of the crucifixion, the cross in visual art, and lastly its representation and place in religious music.

After a helpful introduction outlining the main historical events and Zeitgeist—i.e. the ‘scientific revolution’ or ‘modernity’—of the era examined (1600-1750 CE), the author leads us into the first main part with an exploration of Catholic (Tridentine) notions of the cross. (29-48) According to Viladesau, both the Catholic and Protestant theology of the cross—the question of what the cross does—finds a basis in Anselm of Canterbury’s proposed theory of ‘Satisfaction.’ (30) Concerning the spirituality of the cross however, Catholic theologians differed quite substantially from their Protestant colleagues. Based on the works of Louis Abelly, St Robert Bellarmine, Francis de Sales, and Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, Viladesau posits that the Catholic spirituality of the cross is characterised by its conception of the personal appropriation of the cross’ offered salvation and a focus on the believer’s “participation in the offering.” Through contemplation of the cross, one should participate in Christ’s suffering and consequently be spurred on to regeneration, charity, and imitation. (41, 44, & 46) Both Christ’s self-giving on the cross and the Christian’s faithful, participatory response—depending nonetheless on Christ’s love—constitutes salvation. (41)

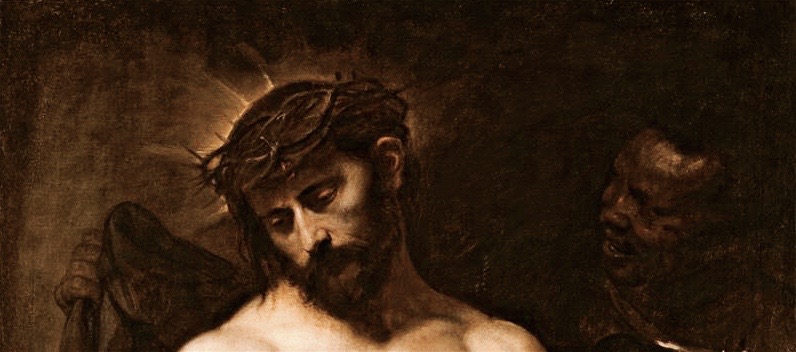

This theological groundwork forms the foundation for Viladesau’s treatment of Catholic visual art (chapter 2) and religious music (chapter 3). Viladesau’s argument is primarily built on the art of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, Francisco de Zurbarán, and Dionigi Bussola. The work of each of them is used to draw out commonalities of Catholic Baroque art and brought in conversation with the underlying theological convictions. Commenting on Zurbarán’s The Crucifixion (1627) for instance, Viladesau contends that the artist aimed, by painting very “life-like representations,” to draw the beholder into the emotional setting of the crucifixion scene “to give a sense of living presence and to evoke an emotional religious response.” (93) Viladesau concludes, based on all these painters, that “Baroque painting and sculpture of the Passion was conceived as a kind of rhetoric, whose purpose was to stir emotions and the mind to compunction and conversion. They achieved this through a sense of ‘pathos’: a presentation of the subject that invited identification and emotional sympathy with suffering.” (121) In Catholic Baroque music, a similar motive is found: the music is used to provide a context that spurs the hearer to participation in the cross-event and graceful collaboration through good deeds and charity. (cf. 134, 136-7, 145)

On Viladesau’s telling, the theology of the Lutheran Baroque emphasised Christ’s substitution in bearing the results of humanity’s sin and Christ’s fulfilment of the Law. (164, 168) The Calvinist Baroque, very much in line with its Lutheran counterparts, drew out Christ’s penal substitution in relation to God’s divine justice. (169-70) In other words, different from the Catholic conception, in Protestant theology, the cross is very much something faithful humanity beholds instead of necessarily participates in to appropriate its effects. Protestant visual art of the cross (chapter 5), which is almost synonymous with the work of Rembrandt van Rijn, reflects these theological emphases. Images of the cross teach the believer about Christ’s condescension, humanity, and final triumph; these representations are thus inherently didactical. (178) A believer’s confrontation with God’s great love, ultimately exemplified in Christ’s Passion, should spark meditation and consequently lead to faith and comfort. (201) Similarly, Protestant musical Passions (chapter 6) try to bring the believer close to the cross: “Bach places the believer at the foot of the cross, addressing Jesus not merely as a savior of the world, but as my loving savior, who has paid the ultimate price for me.” (248) The final part (chapter 7) expounds on the theological and philosophical challenges to the doctrine of salvation through by the cross in the Enlightenment era.

Viladesau’s work succeeds in its aim to elucidate how both Protestant and Catholic Baroque artists try to evoke a proper religious response to the cross-event, in accordance with foundational theological notions of particularly the cross, and soteriology more broadly. The study, however, might be susceptible to the following critique. Probably due to the breadth of the study, theological nuance and detail concerning the different Atonement theories developing in the Baroque era is sometimes wanting. For instance, Viladesau sees Anselm’s theory of ‘satisfaction’ as the ground of all orthodox soteriology in the Baroque era. In asserting this, ‘satisfaction’ becomes a terminus technicus for Anselm’s theory, which was inspired by mediaeval feudalism. Viladesau seems to understand later Protestant explanations of the cross-event as being examples of this underlying theory of satisfaction. Considering that throughout the Baroque era Protestant theologians began to explain the Atonement with other metaphors (primarily Penal Substitution), Viladesau’s insistence on identifying a theological theory of ‘Satisfaction’ underlying the Protestant Baroque simply needs more explanation.

All things considered, Viladesau’s work is highly readable, well informed, and covers a wide array of sources. Although perhaps sometimes lacking in theological detail, Viladesau’s volume gives a very helpful overview of how in two of the major Christian traditions of the Baroque era, theology and doctrine informed and influenced contemporaneous religious expressions of the cross.