O LORD God, to whom vengeance belongeth; O God, to whom vengeance belongeth, shew thyself.

Lift up thyself, thou judge of the earth: render a reward to the proud.

LORD, how long shall the wicked, how long shall the wicked triumph? (Psalm 94:1-3)Dearly beloved, avenge not yourselves, but rather give place unto wrath: for it is written, Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord. (Romans 12:19)

I grew up in the American heartland, where the King James translation continues to be the predominant form of biblical discourse, the Bible of America’s Bible Belt. Most of the people I went to church with in my youth and many members of my family quote verses in their full glory; the language of the KJV has filtered into our discourse, and into our blood, so that these words have become as familiar as our own faces in the mirror.

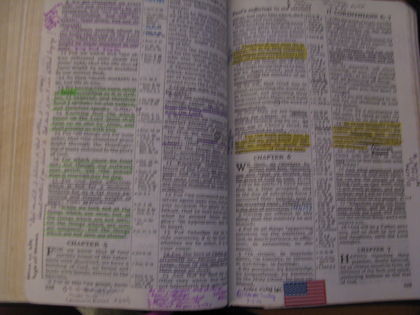

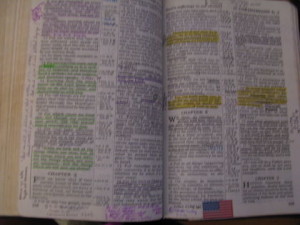

My own King James Bible—although I use it less often for worship, study, or the theological reflection I do—is a particularly American one: a Thompson Chain Study KJV published by the Kirkbride Bible Company of Indianapolis, Indiana, marked up with lots of youthful notes about sermons, preachers, dates I heard a particular message. It could be my grandmother’s Bible, or my brother’s, or any number of other people in the heartland—over four million of these Bibles have sold in the last century.

My own King James Bible—although I use it less often for worship, study, or the theological reflection I do—is a particularly American one: a Thompson Chain Study KJV published by the Kirkbride Bible Company of Indianapolis, Indiana, marked up with lots of youthful notes about sermons, preachers, dates I heard a particular message. It could be my grandmother’s Bible, or my brother’s, or any number of other people in the heartland—over four million of these Bibles have sold in the last century.

Suffice it to say that I come from American Christian stock with a tendency to think that the words of the King James version represent themselves talking, and that by taking ownership of these familiar words they have somehow taken ownership of God—as though this is the secret language to which God responds. So it is that they (or we, although I now stand outside this tradition) tend to conflate God’s will with what we perceive as America’s destiny. To mangle the old saying about General Motors and America, many Americans believe that what is good for America is good for God.

So it is that when Islamic fundamentalists struck the United States on September 11, 2001, the call came bubbling up as if from an American spring: Vengeance. Vengeance! The language of the King James Bible was bubbling down there too: “O LORD God, to whom vengeance belongeth; O God, to whom vengeance belongeth, shew thyself.”

There was little doubt in the American heartland that God was on our side, and in the fashion of holy warriors everywhere—including the holy warriors who flew airliners into American buildings on 9/11—we heard this language of God’s vengeance and took God’s office upon ourselves. The majestic language of the King James Bible stirred American souls to assume God’s office, to, in the words of our past president, strike down evil, even if Christian theology understands that to be God’s exclusive province: “The evil ones have roused a mighty nation, a mighty land. And for however long it takes, I am determined that we will prevail.”

Yet the language of the King James Version’s Letter to the Romans is also the language that reminds us in the heartland that we are not to avenge our hurts ourselves. “Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord.” In the margin of my Bible at Romans 12: 19, the Thompson Chain Reference apparatus says, simply, “Retaliation Forbidden” and “Divine Vengeance.” There seems to be little room for discussion.

It may take this sort of reading between the lines—for we have come to claim the authority of the KJV as our own—but the same stately language that calls Americans to war can also command us to peace, if we will only hear and obey. Perhaps in the next ten years, our anger will die down, and we can once again hear the King James Bible calling us to higher and nobler reactions.

________________________

Greg Garrett is Professor of English at Baylor University, a licensed lay preacher in the Episcopal Church (USA), and the author of over a dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, and memoir. He is perhaps best known for his writing on religion and culture, including The Gospel according to Hollywood, We Get to Carry Each Other: The Gospel according to U2, One Fine Potion: The Literary Magic of Harry Potter, and The Other Jesus. Dr. Garrett writes a weekly column on religion and politics for Patheos, and has also contributed to print and online publications including the Washington Post, Reform, the Christian Science Monitor, Christianity Today, and Poets and Writers.