[EDITOR’S NOTE: The next entry in our series inviting artists to reflect on their creative process is provided by composer Anselm McDonnell. This reflection yields fascinating insights into Anselm’s composition for the In/break exhibition. Using the words of Psalms 42 and 43, which balance the pain of distance and promise of deliverance, Anselm describes how he ‘recast’ the folk tune My Lagan Love, ‘shaping this melody into a musical vehicle for the Psalmist’s words’. Through compositional ‘incursions’, he allowed the words of the Psalms to break into the folk melody, producing a new piece redolent of the mingling of grief and hope that has shaped our spiritual lives during the pandemic.]

The heartfelt keening of Psalms 42 and 43 (likely one text originally) is a powerful poetic expression of grief caused by an affliction that has lain heavily on us for the past year: distance. The Psalmist gives voice to a deep longing and thirst for a series of contiguous blessings that have been removed: God’s face, his peace, his place, and his people. I was drawn to these words as they resonated with my own yearning for God’s worship and people, and with my desire to sing, with avenues for singing cut off in both choral and liturgical settings.

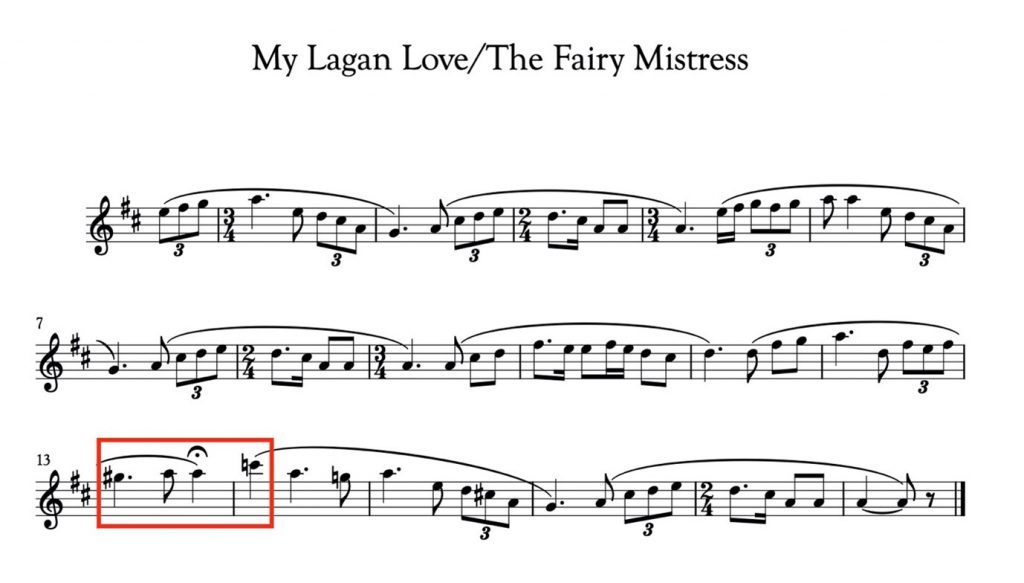

My wife and I are precentors at a Reformed Presbyterian church in Belfast, where the congregation sings metrical Psalms, and I often search for well-known and well-loved tunes to fit these metres. Irish traditional music is a repository of accessible and beautiful melodies that has furnished us with several additions to the church’s repertoire. One of the tunes I had hoped to introduce last year, My Lagan Love, fits the metre of both Psalms 42 and 43. The lyrics of My Lagan Love, commonly credited to Belfast-born Joseph Campbell, speak of a tryst between the writer and the daughter of a Lagan bargeman (although, as is often the case, the tune is older than the words; its origins can be traced to Donegal before becoming obscure). Both the lyrics and music are imbued with a sense of forlornness. The unnamed woman is likened to a leanán sídhe: a faerie lover who abandons or feeds off pining mortals – a common trope in Irish folklore.[1] Musically, the tension of this tale is conveyed by two elements: the mixolydian mode (a major scale with the seventh note flattened, which results in a somewhat pensive quality) and a twist at the apex of the tune created by suddenly slanting sideways into the minor key.

Prompted by the Transept In/break exhibition – and the absence of both professional and congregational singing – I decided to make a straightforward re-harmonisation of the tune with the Psalm texts, for myself and my wife to record from home. As any of the choirs who perform my work will tell you, my penchant for polyphony and thick, unstable harmonies quickly takes my music out of the realm of ‘straightforward’, and such was the case with this work. It quickly became apparent that the intricacies of this melody were provoking a more engaged creative response from me than simply an alternate harmony. Consequently, the piece became an interplay between the source material of the folk tune, and my compositional incursions into its world. These incursions are moments where I deliberately subverted or distorted the original melody: fragmenting it, changing the harmonic direction, stretching its rhythms out to unexpected lengths. I intended to select these moments by relying on my intuition and experience to find suitable points of departure from the folk tune.

Apart from my own musical intuition, however, there was a second influence being exerted upon the direction of my creative process. In his essay Art as Technique, the Russian literary theorist Victor Shklovsky posits that the function of art is to rescue us from the habitualness of life by presenting us with familiar objects or experiences in a manner that is unfamiliar, provoking us to perceive and contemplate them in new ways.[2] As I responded to a work of art which has itself become a familiar object – the melody of My Lagan Love – I was questioning what potential incursions could be used to defamiliarize the journey it takes. The answers were provided through the symbiotic relationship that forms between text and music. The imposition of the Psalm texts onto this melody pointed me towards opportunities to re-examine and recast the music, as the influence of the words subtly seeped through.

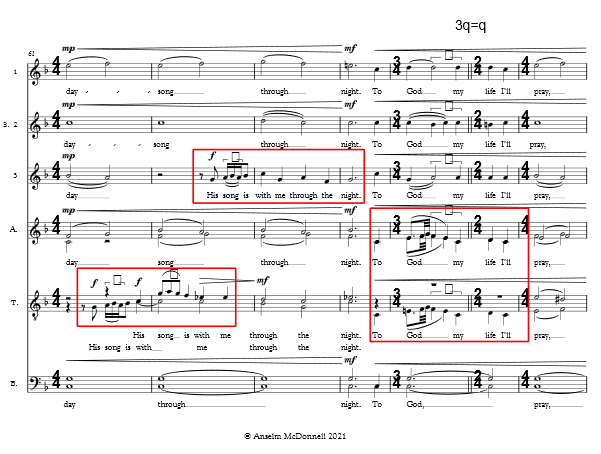

The first opportunity to take the music in a new direction arrived when I set the text ‘With thunder of your waterfalls, deep unto deep does call.’ Prior to this, I had faithfully retained both the original key and adhered to the melody’s contour, passing phrases back and forth between the upper and lower voices. The vivid picture of a stormy sea acted as a springboard for my own musical voice to break in. I used the countermelodies from earlier in the piece to spill over into an imitative passage for the whole choir, the harmony drifting chromatically in several directions. Fragments from My Lagan Love are still present, buried in the dense thicket of voices, occasionally bubbling to the surface. From this point on, I was able to interweave the folk melody with my own materials, which responded more directly to the words. A second example of this is the setting of ‘His loving-kindness… through the day… his song is with me through the night,’ where the Psalmist meditates on the LORD’s loving-kindness, perpetually present through both day and night.[3] This prompted me to respond to the ideas of permanence and gentleness. The basses establish an unmoving foundation of a perfect fifth, while the upper voices gently rock between two chords. Within this contemplative texture, fragments of My Lagan Love are heard rising through the choir.

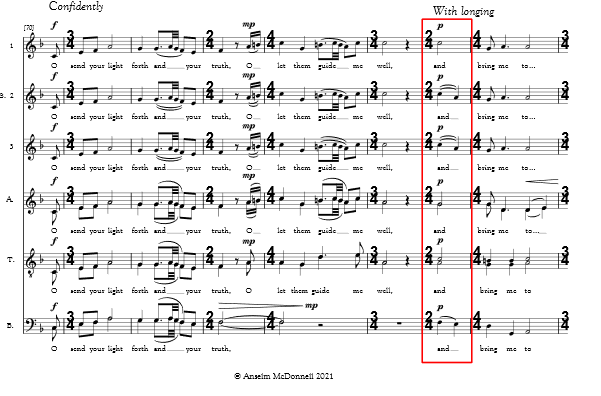

As I allowed the words to shape these moments, I became increasingly aware of a jarring element present in the composition. As mentioned before, the forlorn minor twist in My Lagan Love is an excellent musical complement to its theme of a broken tryst. However, this did not seem to fit with the expressions of faith and hope in the words I was setting. There is a tension in the text of Psalms 42 and 43, in which pain and promise are held together, but their outworking in the Psalmist’s life is different from the experience of the abandoned Lagan lover. Rather than dwelling on the poignant prospect of loss, the Psalmist counters feelings of disturbance with reminders of God’s past faithfulness, and the certain expectation of the LORD’s salvation. This inbreaking of faith caused me to ponder how I could portray the hope that permeates these Psalms as God’s truth intrudes upon the writer’s spiralling downward cycle. The incursion of the minor key into My Lagan Love is both the crux of the melody and the hinge on which its narrative turns. This seemed the ideal point of departure to reinterpret the material to align with the Psalmist’s hopeful message. The first two times this moment is approached in my setting, the melody lands on an extended major chord. The third time, as the Psalmist asks for God to ‘bring me to your holy hill, the place in which you dwell,’ the desperate reaching of the minor interval is removed altogether. The melody peacefully remains on the same note that ended the phrase preceding it, before sinking restfully onto the closing statement.

Altering these chords brought the music into better alignment with the text, but I wanted to acknowledge the powerful juxtaposition of major and minor harmonies that make My Lagan Love such a striking tune. In the setting of ‘His song is with me through the night,’ the rocking chords mentioned earlier lead the choir onto a biting sonority that incorporates both major and minor third intervals. The tension of this moment is released as the choir approaches a strong F-major cadence, the climax of the piece.

As a small, pale reflection, the process of shaping this melody into a musical vehicle for the Psalmist’s words reminded me of Christ’s transforming activity. As he works by his Spirit, using the tools of his living Word, he shapes, refines, and mends. The words of Psalms 42 and 43 were a timely reminder for me that Christ is not limited by distance as we are; his power is not diminished and his reign is not compromised.

[1] In some collections, the tune is called The Fairy Mistress.

[2] Cited in The Art of Biblical Poetry by Robert Alter, Basic Books, 2011.

[3] The theme of God’s nychthemeral protection is found in several Psalms, such as 91 and 121.