In Book I of the Consolation of Philosophy, Lady Philosophy visits her suffering disciple as a bright-eyed woman with a remarkable outfit: “Her garments were of an imperishable fabric, wrought with the finest threads and of the most delicate workmanship; and these, as her own lips afterwards assured me, she had herself woven with her own hands” (1.1).[1]

In Book I of the Consolation of Philosophy, Lady Philosophy visits her suffering disciple as a bright-eyed woman with a remarkable outfit: “Her garments were of an imperishable fabric, wrought with the finest threads and of the most delicate workmanship; and these, as her own lips afterwards assured me, she had herself woven with her own hands” (1.1).[1]

With these words, Boethius places his comforter within a tradition of legendary women who bear divine revelation through humble domestic crafts. Lady Philosophy’s workmanship recalls the arête of Athena, who endows both wisdom and weaving, as well as the noble wife of Proverbs 31, who “seeks wool and flax, and works with willing hands” (v. 13). In the centuries after Boethius, many other writers described women whose crafts symbolized stunning faith. The medieval legends of Saint Lioba say she one dreamt that a purple thread was coming from her mouth. A prophetess in her convent interpreted the dream: purple thread signified her wise counsel, issuing endlessly from the love of God.[2] Much later, the Victorian fantasy-writer George MacDonald created the figure of an eternally young “great-great grandmother” who sits at her mystical spinning wheel, twisting a thread that will always lead her children home. She makes “the finest and strongest” thread in the world, and it is utterly trustworthy, though it often leads her followers on strange and sacrificial journeys.[3]

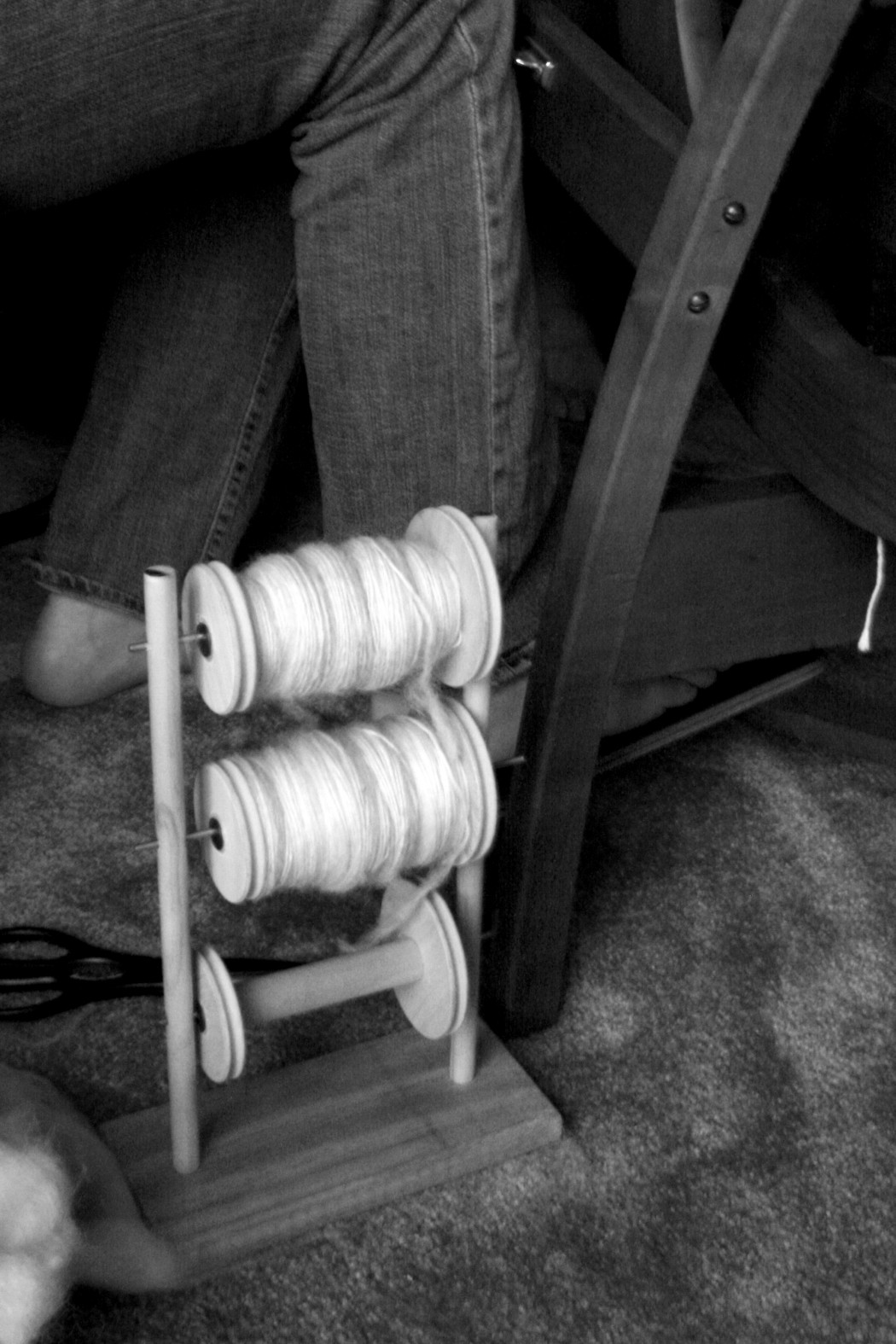

I wish I could say that these noble examples inspired my interest in textile crafts. However, when I learned to crochet and knit as a teenager, I could only say that I wanted to be “useful.” I was an eager and high-achieving student, but by the time I was sixteen, I began to worry that my knowledge was entirely cerebral. Without knowing why, I craved manual work. I began playing with fiber crafts while still in high school, and in the years since I have become an amateur spinner, weaver, and seamstress.

During graduate school, having hand-crafts provided a balance I had missed in high school, and I began to joke that I picked up a new craft with each level I earned toward my doctorate. The steady rhythm of my spinning wheel could calm a brain addled with too many hours at the computer, while sewing a quilt provided a useful analogue the work of patchwork synthesis we call a dissertation. At the same time, making yarn into a sweater reminded me that my academic work—teaching and writing—is deeply useful. My ideas, at their best, might provide a little warmth in a world of cold philosophies and bitter winds.

Most wonderfully, learning these age-old domestic crafts illuminated so many of the dearest metaphors in my faith and profession. Having struggled to caress lumpish wool into strong, thin threads, I understand why we say something is “fine” to mean it would require great skill to produce. By exploring how to create dyes from natural sources, I have come to feel, even as I once knew, how precious purple thread would be to an ancient reader or weaver. Like so many of my foremothers, I have mourned moth-holes in fabric I wove with my own hands, and so I pause in awe to consider Lady Philosophy’s “imperishable” handiwork.

I practice crafts for many reasons: to relax from intellectual work, to learn about history, to clothe myself. Perhaps most importantly, I work wool, flax, or cotton with willing hands because I hope these ordinary, ancient practices, like prayer itself, will draw my heart toward Christ, who is the comfort of all good grandmothers, the bridegroom of the noble wife, the master of Lady Philosophy, and the source of true wisdom.

—

Bethany Bear is assistant professor of English at the University of Mobile in south Alabama. Her scholarly work focuses on nineteenth- and seventeenth-century British literature, and she blogs at bethanyslettersfromhome.blogpost.com

A beautiful message. In this sense, Lady Philosophy seems like the Fates fulfilled or sanctified; the unfolding of divine wisdom ‘diachronically’ and the unfolding of events in their physical sense. And the craft then becomes not just an analogy but a version in little of the same process – we feel it’s aptness with a kind of resounding, inner & outer, tuning fork-like sympathy.

It may be a bit far afield from “soft sculpture”, but the new book of Flannery O’Connor’s cartoons suggests what you are suggesting, and may have been the primary template for some of her stories. I gave Herr Professor Schuler a few samples. You have no doubt heard of Flannery’s backwards walking chicken, the highlight of her life. Well, she worked with linoleum cuts, which like woodcuts all have to be done backwards–and quickly before the medium chills. The better ones are Thurberesque to be sure. But she continued to paint, as much as her lupus would allow. Probably for some or most of the reasons you mention. Really enjoyed this, it’s obviously out of my realm–but so it my son’s passion for wood and metal…and Shire pipes.