Editor’s note: We are very pleased to present the first part of an interview with distinguished artist Penny Warden. In this first part, she discusses her own journey to become a practicing artist and the role of religious art in contemporary culture. In the upcoming second segment, she will discuss the intersection of theology with her own work and comment on some of the technical aspects of her painting.

You became a professional artist after a number of years in a different career. Was that earlier time a conscious time of ‘waiting’ to move into art, or was your move more unpredictable than that? How did those earlier years working in other fields impact your eventual artistic practice?

Despite being top of Art at school and being urged and encouraged by my teachers, sadly my abilities were not acknowledged by my parents who had no interest in the arts. Instead I was encouraged to pursue a career in accountancy in the City of London. Predictably, the accountancy path proved very unsatisfactory for me, and I followed it with various other frustrating and unfulfilling jobs in sales and advertising. In 1981 when I was 24 years old I rediscovered my Christian faith. My growing convictions fuelled a desire to learn more and against all odds – with no particularly relevant qualifications or aptitude – I was accepted into Westminster College, Oxford that same year to study a degree in Theology. After graduating in 1984 I married my husband, a clergyman in the Church of England, and started the PGCE teaching qualification in Religious Studies. It was my mother-in-law who encouraged me to pick up my paints again in my early thirties. Thus for a few years I combined bringing up two small children with being Head of Religious Studies at a prep school, yet at the same time attending a weekly art class. I think it was during these years that I was very conscious of ‘waiting’ to move finally into art. I had a definite yearning to go to art college and an ambition to ‘make it’ as an artist, whatever that meant! The wait came to an end a few years later when I had the opportunity to give up teaching and take up a part-time art degree. Eventually I became a professional artist in my early 40s, and my passion for theology has most definitely impacted my eventual artistic practice.

On a related note, what advice would you offer aspiring artists who hope to follow your path from a different career into full-time artistic practice?

Well, I would say tighten your seat belts and be prepared for a rollercoaster ride! It involves a great deal of knocking on gallery doors, with certain doors opening and some shutting; there are many rejections and barren times, but also good and exhilarating times. You have to roll with the punches and pick yourself up again! Of course, an income is never guaranteed and that is daunting. Also, it can be rather a lonely profession, so you need to enjoy your own company. But there is amazing satisfaction too, and I never take it for granted when I sell a painting through one of my galleries. It is a wonderful privilege when someone chooses my artwork to place on the walls in their homes.

How has your artistic style or practice changed over time?

When I started painting again in my early thirties, my work consisted mainly of commissions for portraits. They were very technical and realistic, and I was able to utilise my natural ability. But I was also learning to be more fluid and creative whilst attending life drawing classes. However, I knew I needed to go to art college and do a degree in order to really liberate my talent and my thinking. Art college helped me to find my own unique voice. I didn’t complete my degree though, and in fact I left the course after 18 months. I became very frustrated with the restrictive and formulaic approach to the creative process at this particular institution, as well as having to write numerous essays and a dissertation. Since I already had a degree in Theology I didn’t feel the need to complete the final years simply in order to obtain a degree. I was also frustrated with the lecturers at the time because very few art skills were taught.But that didn’t matter in the end since, as Patrick Heron says in his book Painter As Critic,‘The artist does not exist whose so-called vision is finer than his so-called technique: everyone does the utmost he is capable of doing: no one has a vision in excess of his power to materialise that vision’. I taught myself how to use oil paints to suit my own style of painting. I’m certainly not a conventional oil painter! In fact, I would say that I am a self-taught artist. However, I did pick up one useful piece of advice, for which I will always be grateful, and that was a remark by one of my lecturers who said, ‘When in doubt, Penny, throw a can of paint at it!’ So I did! Instantly that did something. It freed up something in me – it was a springboard for a new language. So my artistic style went from realism to a form of action painting, by means of vibrant colours splashed and spattered on the canvas in an arbitrary, though deliberate, manner.

What does ‘Christian art’ mean for you in today’s culture? What kind of ‘Christian art’ can communicate most effectively in our culture?

To paraphrase TS Eliot, I think theology has to be communicated afresh in every new generation, and Christian art can and should be part of that process, as indeed it always has been, apart from dark periods of history such as the iconoclasm controversies. Christian art can have a power which communicates with people beyond words.

Christian art is a very wide term and it can take many shapes and forms, and there are some high-profile artists out there today such as Bill Viola and Anthony Gormley who are making incredible work with theological themes. However, beyond the famous names, there are countless anonymous artists working to communicate Christian themes through Christian art.

As a trustee of the Christian Arts Trust, I am aware of the immense variety, creativity and vibrancy of the Christian arts scene in our culture today, whether it be painting, sculpture, poetry, music or theatre companies producing excellent plays. This charitable trust exists in order to provide small grants to seedling Christian arts projects around the country so that they can get off the ground and become established.

It is a charity close to my heart, because before becoming one of its trustees I was one of its beneficiaries. The trust saw the potential in my Phoenix paintings to communicate the Christian message in a cathedral context. At that time I had a vision for taking these paintings on a tour of English cathedrals. Their financial backing—which several years later I was able to repay—enabled the Phoenix paintings to eventually tour ten English cathedrals over a period of four years. I believed that the Phoenix paintings were a kind of ‘visual sermon’ communicating the Christian message, as well as the universal themes of death and resurrection embedded in the Phoenix image, in a very dramatic and powerful way.

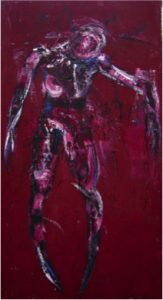

Phoenix One. 90 x 180cm. Oil on board

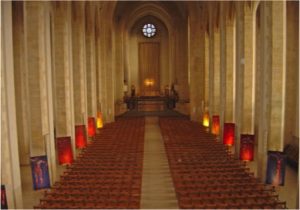

These fourteen life-size Phoenix paintings—each with a single androgynous figure, hanging somewhere between death and resurrection—were often displayed down either side of the cathedral nave with their own easels and spotlights. They stayed in the cathedrals for up to two months, typically but not always, during Lent. As the viewers looked down the nave, the seven pairs of paintings across the nave went from ‘darkness to light’, in other words from ‘death to resurrection’. Dramatically the background to these individual large canvases went from black through a sequence of purples, blues, reds, oranges to yellows the closer they got to the altar.

I use this as just one example to demonstrate how these relatively abstract paintings can be used in ancient buildings to communicate Christian and universal themes both to casual visitors and worshipping congregations who are increasingly visiting the great cathedrals in our land.

Guildford Cathedral, 2005

A second powerful example of how Christian art can communicate in contemporary culture was exemplified in the summer of 2016 in Blackburn Cathedral. My paintings had already been in the cathedral for eleven years, but this was the first time they had been used as the foundation for a national flower festival in the cathedral. I have long thought of my paintings as separate entities which have a life of their own now that they sit in the cathedral, akin to children who fly the nest! Little did I know that my paintings would ‘give birth’ to other visual art, but that is what happened. The artistic director of the flower festival insisted that contributors based their floral sculptures and creations on one of my Stations of the Cross. Indeed, those who applied to be included in this important flower festival had to submit a short essay on how they were going to interpret each station within their flower displays. The grandeur, magnitude, variety, creativity and artistry of these huge flower displays was remarkable, bringing in thousands of visitors to the cathedral during the week. The significance of the event was picked up by The Timesnewspaper. This example demonstrates how Christian art can speak to different people in a variety of media.

Mig Kimpton’s interpretation of The Crucifixion.

Is there a place for the didactic in religious art? Can good art be didactic?

As well as the foregoing examples of Christian art being used to communicate in contemporary culture, Blackburn Cathedral has consciously and deliberately used my paintings in a didactic fashion in interfaith dialogue. Blackburn has an extremely large Islamic community, and the cathedral is at the forefront of interfaith dialogue within the town, using its influential position to be theologically inclusive and to develop greater social cohesion. They have used my art with groups of schoolchildren from different faith backgrounds. By bringing children into the cathedral to interact with the paintings they have sought to establish a dialogue between the different faiths and attempted to find common ground and mutual understanding over universal human concerns that naturally arise out of the Stations of the Cross, such as suffering, compassion, and hope of life eternal.

Additionally, the Dean and chapter of the cathedral produced a beautiful booklet on my Stations of the Cross which was sent out to every parish in the diocese. It included photographs of my paintings and a commentary on each one written by one of the cathedral canons. The purpose of this book was purely didactic; it overtly sought to teach the Christian gospel in a new and accessible way through the art, encouraging confirmation groups to come to the cathedral and use the stations for educational and devotional purposes. Importantly, the Canon brought his own insights into the paintings, even alighting on things that I had not thought of myself, thus showing that the Christian and universal themes embedded within such religious art are bigger than the artist.

So I do believe that there is a place for the didactic in religious art and that good art—or even less good art—can be didactic. Of course there can be ‘art for art’s sake’, but there can also be art for the sake of some higher purpose. I would place Christian art in this latter category as it seeks to educate not only intellectually but spiritually, resulting in faith, devotion and ultimately in changedlives. However, I would add the important caveat as developed by Patrick Heron (see below) that the artist should not make the audience the prime focus of the artistic process.

I do like what the Venerable Bede argued in the eighth century, that religious art fulfils both an ‘instructive’ function and a ‘recollective’ function; it is there to teach people and also to help them remember what they have learnt. In other words, looking upon a representation of Christ was meant ultimately to lead to the imitation of Christ. Hence religious faith becomes a possible result of engaging with the painting, and I hope that has been true of my paintings.

Part of my general research into the function of religious art also focused on St Bonaventure, the thirteenth-century Minister General of the Franciscan Order, who established a threefold defence of the purpose of religious art, and I was struck by his insight.

Firstly, that images of Christ were made for the uneducated so that they could understand what they were not able to read for themselves in the Scriptures. Secondly, that spiritual devotion is much more likely in those who see images of Christ than in those who merely hear about his deeds. And thirdly, that His deeds are more likely to be remembered if they are seen rather than just heard. Thus a depiction of the suffering Christ served as a reminder of the sacrifice He made for the sake of humanity. The feelings of gratitude, pity or pious remorse it inspired in the devout were intended to deepen their love of God. As for Bede, the artistic representation of Christ could lead to the imitation of Christ, and faith might grow by engaging with the painting.

The contemporary artist Tim Patrick writes persuasively of the didactic nature of art whereby ‘a painted image can be transformative and can reinvigorate a subject’. A particular event at Blackburn Cathedral powerfully illustrated this. In 2006, the American Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, was invited by the then Defence Secretary Jack Straw MP to visit his constituency in Blackburn. Part of the visit included a tour of the cathedral, during which she lit a candle underneath one of my Stations of the Cross, Christ Laid in the Tomb, in memory of the Boxing Day tsunami victims and for world peace. The episode was captured on the BBC and other broadcasting organisations from around the world. The significance of this was powerful, because the Dean of the Cathedral had sponsored this particular painting in memory of his daughter-in-law’s village that had been destroyed in that natural disaster. Thus contemporary art in this religious context had a powerful role in being a vehicle for expressing deep human emotions.

Condoleezza Rice viewing Jesus in the Tomb

What other contemporary artists, whether painters or otherwise, do you think are making compelling art of theological relevance?

Much of Antony Gormley’s work strikes me as compelling and theologically relevant. For example, his wonderful temporary installation Flare IIin the Geometric Staircase of St Paul’s Cathedral in 2010. In addition, his controversial 2013 Sculpture for Derry Walls, displayed in Londonderry when it became the European capital of culture, spoke powerfully to the community about the Troubles between Catholic and Protestant in Northern Ireland. The violent reaction that it provoked was for him confirmation that‘art could have a social purpose and it could engage with real issues in real communities’.In fact he uses theological language to describe his experience as ‘my baptism’. Also Mark Wallinger’s Ecce Homo, a temporary occupant of Trafalgar Square’s fourth plinth. Clearly the video artist Bill Viola’s permanent large-scale installations in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Of course there are many contemporary musicians who make compelling art of theological relevance. For example, Stormzy and his ‘Blinded by Your Grace, Pt. 2’. The Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby particularly likes the line ‘I stay prayed up then I get the job done’.

LINKS

www.thejourney.me.uk

www.pennywarden.com

http://christianartstrust.org