Jon Coutts is currently studying forgiveness in Karl Barth’s ecclesiology at the University of Aberdeen, having moved from Canada where he did a Master’s thesis on G.K. Chesterton at Briercrest Seminary.

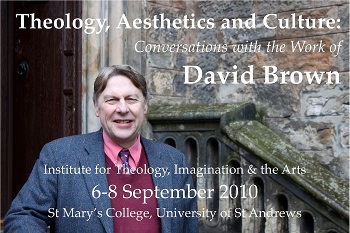

The ITIA conference in St. Andrews was for me an introduction to the work of David Brown. Thus I was very appreciative of the handout summarising the five volumes under scrutiny and was inspired by the plenary sessions to delve deeper into a couple of them on my own. As someone who did graduate work in theological fiction and is doing postgraduate work in the theology of Karl Barth, I must confess that during the plenary sessions and short papers I was both riveted and fidgety. I love a fine marriage of theology and art, and yet am sensitive to theology’s potential to be little more than anthropology with a loud voice.

Leaving anxieties aside for a moment let me begin with conference highlights. I enjoyed each of the plenary presentations and especially appreciated the respectful candour in which David Brown’s work was both lauded and challenged. Particularly memorable for me were the papers by Margaret Miles and Tina Beattie, in which the former reflected on revelation as something which carries on into the re-readings and re-imaginings it incites, and the latter illustrated the point with an artful display of sainthood’s increasingly redemptive feminization up to the late Middle-Ages. The trajectory of New Testament mutuality and nurturing biblical community seemed to dance right before our eyes.

But there was something in the air at the conference which I found unsettling; something I also felt at the SST conference earlier this year. Discussions of art and theology tend to lose me when they implicitly or explicitly assume that reflections on creation, imaginations of the divine, evocations of wonder, or even expressive responses to revelation can be said to speak of God. In these situations I find myself asking: When is art merely anthropology? When is anthropology theology?

Often when theology and art is questioned like this, it sounds like a call for Christian criteria—at which point the dogmatics get muddled and the arts feel muffled. What criteria can humans set up to determine what counts as divine revelation? What good is imagination if all the lines are already drawn? Is it the job of dogmaticians to design stencils for artists? Is it the job of artists merely to think outside-the-box? Certainly these tensions are not unique to theology. Imagination and truth are always wrestling with each other, it would seem. I guess what I’m most interested in is whether in Christianity these ought to enjoy a certain measure of the ministry of reconciliation? Can they dance where others wrestle?

Chesterton said that painters are at their best when they put canvas in frame and draw a line somewhere, just as athletes excel when there are rules and a field of play. In a similar vein, at the conference Jeremy Begbie suggested that the specificity of the Word of God is not constricting for the arts, but liberating. As Barth would have it, human freedom is not found in autonomous decision but precisely in obedience to God.

Though Barth has not often been viewed as a proponent of theological art, the final volume of his Church Dogmatics proposed that since the Word of God is living and active in His creation we should expect to hear Him speaking freely through other words. We should expect to see the Light of Christ lit up in little lights all over the world—not because they hold a latent indication of who or what is God, but because they are a good canvas on which the Spirit can draw. Seen in this way I would suggest that discussion of criteria may aid discernment, but guarantees nothing. It is incumbent upon artist and appreciator alike, rather, to submit themselves to the living Word of God in both expression and interpretation. Where this is not done we may have art, but we likely do not have theology.

Those are some good questions—enjoyed the post. I agree with your conclusion, although I might add that we may just have bad theology when there isn’t that submission either in expression or interpretation.