Danny Gabelman is a PhD candidate in ITIA working on the fairytale levity of George MacDonald. Originally from Colorado, Danny is marrying a beautiful English girl this summer and has plans to remain in the UK for the foreseeable future.

* * *

In the spirit of whimsy, I shall present this post through a series of inter- and un-related sketches or doodles rather than linear argumentation.

Whimsy is the gamesome servant of the imagination.

Generally speaking, whimsy is related to Aristotle’s principle of association or what Coleridge terms ‘fancy’. It is a frolicsome cousin of memory, the power by which the mind makes connections with the past. Instead of associating the obvious and the similar, however, whimsy combines the unexpected and the disparate. Whimsy does not connect flies with moths but with children’s toys as in Lewis Carroll’s rocking-horse-fly.

Generally speaking, whimsy is related to Aristotle’s principle of association or what Coleridge terms ‘fancy’. It is a frolicsome cousin of memory, the power by which the mind makes connections with the past. Instead of associating the obvious and the similar, however, whimsy combines the unexpected and the disparate. Whimsy does not connect flies with moths but with children’s toys as in Lewis Carroll’s rocking-horse-fly.

‘Good poets’, says W. H. Auden, ‘have a weakness for bad puns’. Puns are whimsical because they harness together ideas or images through the very thin tendril of auditory similarity. The best puns (or by another reckoning the worst ones) have the thinnest threads drawing together the most unexpected of elements. ‘Atheism is non-prophet’.

Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a good metaphor of whimsy. He is the ‘merry wanderer of the night’ that delights in creating mischief. He traverses traditional boundaries and facilitates the meeting and intermingling of different worlds and perspectives. He comically disorients the lovers, and he brings the ass-headed Bottom into contact with the ethereally beautiful Titania. Perhaps because he is a servant and vassal of Oberon, however, Puck is ultimately benevolent. He does not wish to offend but desires to make friends and amends. A malevolent Puck would be a nightmare rather than a dream.

If the imagination more generally is the faculty of mind that selects, shapes, and forms, then whimsy is the faculty that discovers, fetches and carries. It is the finder rather than the maker. It is like a playful golden retriever. This faculty of finding unexpected connections necessarily precedes and continuously supplies the more grand and glorious primary imagination.

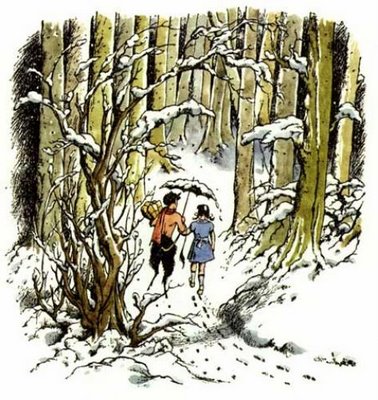

A famous example of the whimsical imagination: C. S. Lewis’ Narnia stories began as a series of images—‘a faun carrying an umbrella, a queen on a sledge, a magnificent lion’. These images just ‘bubbled up’ and the association of the images with Christian meaning was part of the bubbling. These whimsical bubbles were the seeds that grew and blossomed into mature works of art.

A famous example of the whimsical imagination: C. S. Lewis’ Narnia stories began as a series of images—‘a faun carrying an umbrella, a queen on a sledge, a magnificent lion’. These images just ‘bubbled up’ and the association of the images with Christian meaning was part of the bubbling. These whimsical bubbles were the seeds that grew and blossomed into mature works of art.

Whimsy is the froth that rises to the surface. Like bubbles joining together air and water, whimsy unites two distinct elements into a new form that plays between the borders of different realms.

Whimsy is sometimes denigrated because of its lack of seriousness. Yet perhaps it is fairer to say that whimsy seriously (though by necessity not gravely) calls seriousness itself into question. To the extent that ‘seriousness’ is associated with pride (taking the self too seriously), whimsy is herein aligned with a core Christian teaching. As Chesterton observes, ‘angels can fly because they take themselves lightly’. Whimsy can help loosen the bonds of seriousness that bind the self within itself.

Wisdom’s Play in Proverbs 8 is a good description of whimsy: ‘I was beside the master craftsman, delighting him day after day, ever at play in his presence, at play everywhere on his earth, delighting to be with the children of men.’ Not the master craftsman but the frolicsome spirit that sports and plays everywhere and with everything.

Whimsy as the master of the imagination is a potentially terrifying prospect, but without whimsy as its servant the imagination would likely be crippled. A Christian aesthetics—given Jesus’ claim that in the kingdom the last shall be first—should be particularly sensitive to servant faculties like whimsy, no matter how low or frivolous they might at first appear.

What a delightful post! I’m also doing my doctoral work on MacDonald, and two weeks ago I lead my literature students through “The Light Princess.” I may have to send this post to them.

Oh, dear. Apparently advanced work in English does guarantee good proofreading. I meant to write, “Two weeks ago I *led* my students….” Sorry.

thank you so much for the whimsy/pride connection. and for pointing out whimsy’s leavening capacity ;’]

Finding GMD’s creative work–not to say deadly serious–but maybe prophetically serious. but was he like that in person? his son remembers him often possessed of gaiety more than any other in a gathering. i liked reading about his boyish mock sermons in GMD & His Wife.

I am glad that you enjoyed the connections.

Chesterton says of MacDonald that his was the ‘gravity of a child at play’, and I find this paradox present in much of his creative work (though admittedly not all). The three books that most people seem to focus on (Lilith, Phantastes, and At the Back of the North Wind) do convey a sense of prophetic seriousness, but his shorter fairytales are much lighter and more clearly whimsical.

Like most people, MacDonald had many different modes, but he certainly had a strong playful side. He apparently was something of an innocuous dandy and loved dressing up in all his highland finery. Great friends with Lewis Carroll with whom he would laugh heartily. I also love the story of MacDonald during Christmas when he would invite poor children to his house, give them cakes, play games with them, read them fairytales, and then tell them the Christmas story.

the infinite or never ending poem in At the Back of the North Wind is very light, lightness and healing. living whimsy, full of everything good.

Yes, indeed. MacDonald’s nonsense poetry is some of the finest. Not as calculated as Carroll’s nor as capricious as Lear’s. To quote Chesterton once again (it is hard not to on the subject of whimsy) MacDonald wrote ‘celestial nonsense’.

Well said, sir. As usual, you’ve given me quite a bit to think about. This all is starting to form a cohesion in my mind, as fauns with umbrellas and golden lions align with porcelain heads and magpies. Thanks.

My pleasure Mr Pond (sounds like Mr Bond). Thanks for linking it to your blog, and congrats on your poetry publication.

Really enjoyed this post. I have always associated whimsy with “fresh air” — a point you get at, I believe. Efforts in imagination and art-making is difficult labor. As L’Engle puts it, the artist strives to bring order out of chaos. Much of the time, the chaos seems daunting, however; but whimsy, with it’s blithe connection-making, often provides the scaffolding to labor once more.