It’s 1965. Don Draper, the man in the grey-flannel suit, is somewhere out there in the midst of full existential crisis. Twenty years after World War Two, America’s victory culture has run stale. The hope and promise for a new generation of Americans died near a grassy knoll in 1963. America has embraced a culture of consumerism and electronic media. That new, Think Young®, generation found solace in fancying themselves the Pepsi Generation®. The American dream is for sale. Dylan has gone electric. Christmas trees are made of aluminum.

Cue Phil Specter; cue Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra:

It’s a marshmallow world in the winter,

When the snow comes to cover the ground,

It’s time for play,

It’s a whipped cream day,

I wait for it the whole year round …

45 yeas after the fact (December 9, 1965) we forget this almost apocalyptic scenario in which Charles Schulz’s first animated Peanuts special aired on American television. As Gilles Deleuze points out, animation has an altogether different technological lineage than cinema –it’s more long-exposure photograph than the snapshot or sequences of privileged instances. And because of this, animation is more of a ‘literary’ genre than cinema, but that is precisely the tonic Shultz offers us. But now I’m getting ahead of myself.

We need to begin with the problem: the America of late-capitalism. It is a supersensuous world given over to material comforts mass-re-produced through the machinery of advertising and mass media. As early as 1961, Daniel Boorstin referred to this troubling historical phenomenon as the pseudo-event in his book The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America. Jean Baudrillard called it hyperreality. This has been the focus of my work at the Institute for Theology, Imagination and the Arts: what is the appropriate theological response to the Matrix?

A Charlie Brown Christmas isn’t the answer, but it does a brilliant job at taking a crack at the problem. One of the necessary features of the early Charlie Brown specials was that there were no adults. And, eventually, if you did hear an adult, their voice was as unintelligible as a message received by SETI. This brilliant device allows adults to accept Charlie Brown’s existential crisis as our own. This is how we meet our main character –in full existential crisis.

And this is the first general point I want to make about the Christmas movie genre. The biblical Christmas story is not a ‘silent night’; it is set in a world of military occupation, and culminates with mass infanticide. While indeed romantic, the Christmas story is of a particular apocalyptic romanticism. The Christmas story is a story of hope birthed in fire. J. R. R. Tolkien understood this apocalyptic romanticism very well. Forged in the rat and lice infested trenches of World War One, Tolkien understood that in the Christian faith we are redeemed by a story, but the only way to sub-create story well is to root it in the dregs of existential struggle. Longing for what is lost without tasting blood and toil is nothing more than saccharine sentimentality.

And this is the first general point I want to make about the Christmas movie genre. The biblical Christmas story is not a ‘silent night’; it is set in a world of military occupation, and culminates with mass infanticide. While indeed romantic, the Christmas story is of a particular apocalyptic romanticism. The Christmas story is a story of hope birthed in fire. J. R. R. Tolkien understood this apocalyptic romanticism very well. Forged in the rat and lice infested trenches of World War One, Tolkien understood that in the Christian faith we are redeemed by a story, but the only way to sub-create story well is to root it in the dregs of existential struggle. Longing for what is lost without tasting blood and toil is nothing more than saccharine sentimentality.

And so, on their way to participate in the harmonious ritual of skating at the pond (a hard metaphor for the status quo of mid-century material America) Charlie Brown pauses to tell us what so many millions of American’s experience during the holidays –something’s wrong with him; he doesn’t feel the way he’s supposed to feel; he isn’t happy; he doesn’t understand Christmas.

But the peaceful nostalgia of the ‘pond’ isn’t as it seems. Long before Snoopy was embalmed by corporate pirates and stuck on the MetLife blimp, he was used by Charles Schulz as a Loki figure. In what turns out to be a brilliant visual essay on the seductive but soul numbing ride of late-capitalist pseudo-reality, Snoopy gracefully glides around the pond and then quickly pulls the Peanuts gang along with him. It’s awkward. At first they are unsure about what is happening and then it is embraced as a joyride. But when you watch the faces of the children during the close-up, they begin to change, one by one, from excitement, to confusion, to fear. Then, just as quickly, they are all cast off.

But the peaceful nostalgia of the ‘pond’ isn’t as it seems. Long before Snoopy was embalmed by corporate pirates and stuck on the MetLife blimp, he was used by Charles Schulz as a Loki figure. In what turns out to be a brilliant visual essay on the seductive but soul numbing ride of late-capitalist pseudo-reality, Snoopy gracefully glides around the pond and then quickly pulls the Peanuts gang along with him. It’s awkward. At first they are unsure about what is happening and then it is embraced as a joyride. But when you watch the faces of the children during the close-up, they begin to change, one by one, from excitement, to confusion, to fear. Then, just as quickly, they are all cast off.

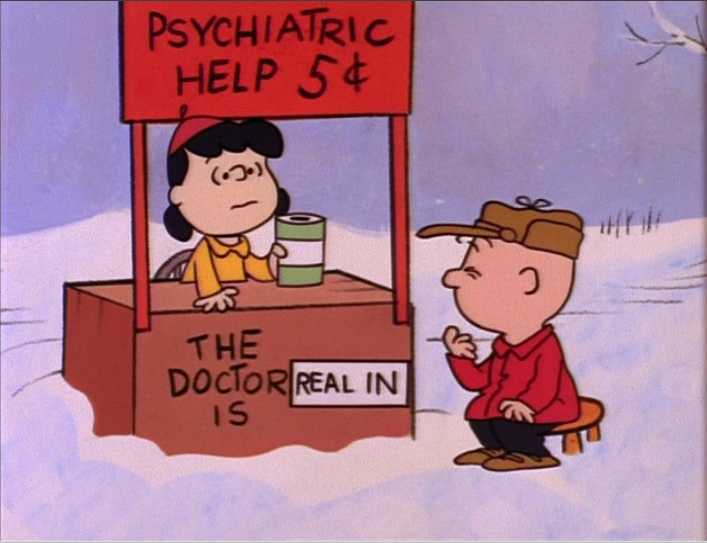

Like Betty Draper, Charlie Brown turns to the mid-century authority of psychotherapy, which attempts to label and solve his existential despair by identifying his phobia. In a statement that, to this day, I still can’t quite wrap my brain around, Schulz tells us that the Doctor is both ‘real’ and ‘in’. Is the doctor ‘reeling in’ her bait? Is the doctor not just ‘in vogue’ but ‘really in vogue’? Either way the word ‘real’ is operative. Reality is hyper-material. For a civilization consumed with immediacy and the materialization of the unseen, the answer to human angst is scientifically diagnosable. Discontent is a physical / social malady.

Like Betty Draper, Charlie Brown turns to the mid-century authority of psychotherapy, which attempts to label and solve his existential despair by identifying his phobia. In a statement that, to this day, I still can’t quite wrap my brain around, Schulz tells us that the Doctor is both ‘real’ and ‘in’. Is the doctor ‘reeling in’ her bait? Is the doctor not just ‘in vogue’ but ‘really in vogue’? Either way the word ‘real’ is operative. Reality is hyper-material. For a civilization consumed with immediacy and the materialization of the unseen, the answer to human angst is scientifically diagnosable. Discontent is a physical / social malady.

But Schulz keenly turns the issue on its head. “All right now. What seems to be your trouble?,” asks Lucy. “I feel depressed. I know I should be happy, but I’m not,” Charlie Brown confesses. “Well,” replies Lucy, “as they say on T. V. …” This is pure Daniel Boorstin. This is pop-science as pseudo-event. This is human therapy and soul searching in an age of hyperreality.

Back to the Christmas movie. When Charlie Brown finally confesses that his trouble is Christmas and he just doesn’t understand it, Lucy also confesses her own disappointment. But she can only describe it in material terms. She’ s disappointed because she doesn’t get what she really wants –real-estate. Her prescription: Social involvement of the highest order. Lucy offers Charlie Brown more seduction … become a director! And with a beautiful mid close-up (an aesthetic technique painfully lost in future Peanuts movies) Charlie Brown is seduced.

Back to the Christmas movie. When Charlie Brown finally confesses that his trouble is Christmas and he just doesn’t understand it, Lucy also confesses her own disappointment. But she can only describe it in material terms. She’ s disappointed because she doesn’t get what she really wants –real-estate. Her prescription: Social involvement of the highest order. Lucy offers Charlie Brown more seduction … become a director! And with a beautiful mid close-up (an aesthetic technique painfully lost in future Peanuts movies) Charlie Brown is seduced.

And so we continue to journey into the heart of the modern American Christmas labyrinth. Snoopy tries to find the true meaning of Christmas by entering a cash contest. Little sister Sally wants what she has coming to her … her fair share … in $10’s and $20’s. Cut to the Christmas play. In part two we will see how this apocalyptic setting provides the necessary backdrop for the collision of modern sophistication with the audacity of the Christmas narrative.

Reno has a PhD from the University of St. Andrews Institute for Theology, Imagination, and the Arts and spent 18 months working for Terrence Malick on The Tree of Life. He has been blogging since 2004—all of which he considers folly since it happened before meeting his wife and soul-mate, Melissa. He is currently working on a book about Iconography, Cinema, and Memory, and is writing two feature screenplays with Melissa.

It is worth watching the Christmas special following the article: http://www.hulu.com/watch/198677/a-charlie-brown-christmas. The psychiatric scene between Charlie Brown and Lucy is definitely worth a look for its over the top commentary on the surreal state of US society in the 1960s (the commentary above nails this). It starts at minute 4.22.